This Article From Issue

November-December 2005

Volume 93, Number 6

Page 571

DOI: 10.1511/2005.56.571

Nature photographers often compose close-up shots of animals or plants, but not Bernhard Edmaier. He's above all that—literally. A former civil engineer and geologist, Edmaier specializes in aerial photography of natural landscapes. His latest book, Earthsong (Phaidon, $59.95), is an oversized treasure trove of pictures that showcase water, earth and vegetation on six continents. The photographs are beautiful and powerful, their colors sumptuous, their composition inspired.

Edmaier has arranged the work in four sections: "Aqua" (rivers, hot springs, swamps, ice boulders, crater lakes, sandbanks, coral reefs, mud pools); "Barren" (glaciers, limestone mountains, volcanic cones); "Desert" (dunes, lava fields, sandstone, canyons, salt lakes, dry riverbeds, badlands); and "Green" (mangrove forests, marshes, algae, cloud forest, grasslands, meadows, alluvial woodlands).

From Earthsong.

These natural tableaux, often photographed from a perspective that renders the resulting image abstract, are testimonials to the physical forces that shape our world. The pictures capture the underlying order and inherent drama of a changing Earth with contrast and detail that could be characterized as painterly or sculptural, except that no human artist could manufacture such organic subtlety. Watersheds laced with rivulets are one of Edmaier's favorite subjects; they call to mind similar patterns found in branching blood vessels and spreading tree limbs. Other motifs include the chromatic extravagance of minerals, the sinuous ripples of dunes and the naked beauty of weathered rock. Be forewarned: You'll be painfully tempted to cut out pages and hang them on the wall.

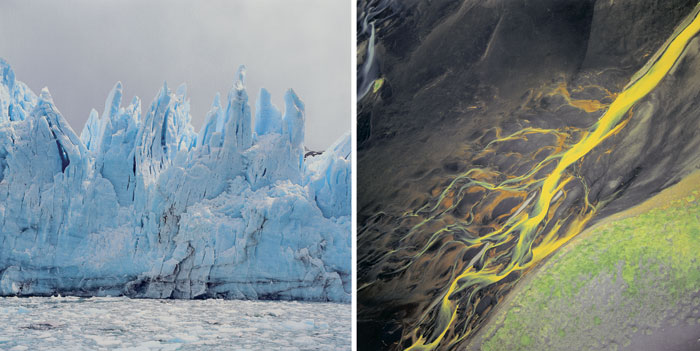

In the pair of pictures above, on the left splintered towers of ice at the tip of the Perito Moreno Glacier in Argentina sag under their own weight until they shatter and fall into the sea, and on the right a shallow stream emanates from a marshy area on the south coast of Iceland. The water is colored yellow by iron minerals dissolved from a streambed of black volcanic rock. A sparse blanket of grass holds together a sandbank separating the marsh from the ocean.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.