Uncovering Ancient Corrections

By Fenella Saunders

Pigment fluorescence reveals artistic revisions beneath Egyptian tomb murals.

Pigment fluorescence reveals artistic revisions beneath Egyptian tomb murals.

The intricate and extensive murals that adorn the walls of ancient Egyptian tombs are no doubt masterful works of art, but their method of creation has long been thought of as having been a regimented production line rather than a free-flowing artistic process. Various levels of artisans were relegated to adding only their assigned layers to each of the illustrations, leaving little room for rethinking the approach. The style used to depict the poses, colors, and decorative elements of deities or others was also highly formalized, not left to the imagination of any particular artist. However, advances in imaging technology have now uncovered corrections and revisions to the tomb figures, bringing into question the accepted view of the process of these Egyptian artists millennia ago.

Archaeologist Philippe Martinez of Sorbonne University in France and a large team of his colleagues describe how they revealed these alterations in the July 12 issue of the journal PLOS ONE. The researchers were examining the tomb chapels of high-ranking officials near the ancient city of Thebes (now Luxor) from what’s called the New Kingdom, which lasted from about 1549 to 1069 BCE, encompassing the 18th to 20th dynasties. “The walls of these shrines were often decorated, representing the dead in his dutiful life on Earth as well as his expectations for a bright future in the netherworld,” Martinez and his colleagues explain in their paper.

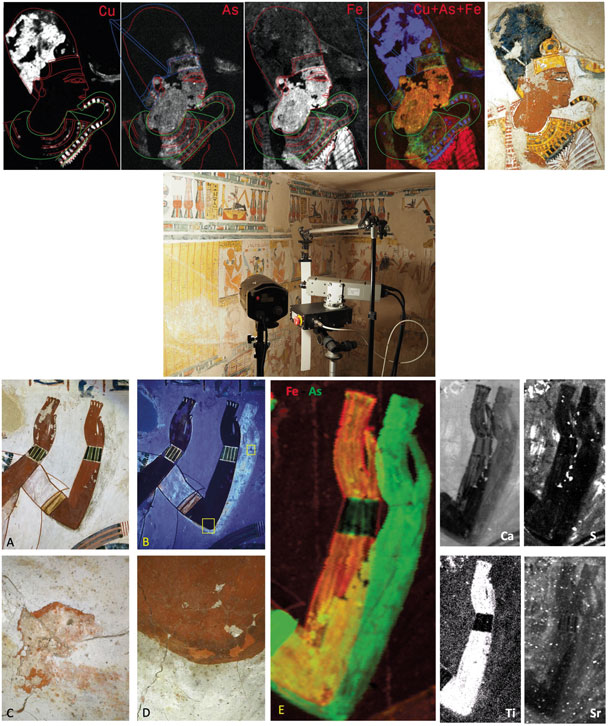

Previously, the pigments used in these tomb scenes had been analyzed mostly by taking tiny samples back to laboratories. But the team of researchers had created a portable version of an imaging device that uses x-ray fluorescence to look at pigments, without contact or damage, while still in place in the tombs. The pigments used by ancient Egyptian artists are suitable for this type of imaging, because the different elements fluoresce at distinct wavelengths when they are bombarded with x-rays, and the rays can penetrate the top surface of paint to reveal other elements underneath. This portable x-ray fluorescence (pXRF) device is small enough to be checked luggage on an airplane, the team notes.

Top and bottom from P. Martinez et al., PLOS ONE 18(7):e0287647. Middle: M. Alfeld et al., Comptes Redus Physique 19:625.

The researchers became interested in focusing their work on artistic corrections when they were examining a known revision that had become slightly visible through the millennia-old wear and chemical reaction of paint, in the tomb chapel of Menna, an overseer under Amenhotep III, 1391–1353 BCE. The revision was made to the position of Menna’s arm, shown in a ritualized pose of adoring Osiris (see figures above). One surprise the team found was that the pigments used in the original and the corrected arms have different compositions, with the first version high in arsenic (common in realgar, a red pigment) and the revised version containing more iron (common in red ochre). That difference could mean that the correction was made by another artist at the same time using a separate batch of pigment, or that the change happened later. The purpose of the rather small position adjustment remains unclear, however.

The second tomb chapel the team examined belonged to Nakhtamun, chief of the altar in the Ramesseum temple, in about 1100 BCE. Because this tomb features a portrait of Ramesses II, it has usually been dated to his reign. However, some inconsistencies with standard Egyptian iconography, including beard stubble and an Adam’s apple, inspired Martinez and his team to take a closer look. Their pXRF showed signatures of copper, characteristic of the pigments Egyptian blue and green, even though these colors are barely visible now. Another hidden detail they revealed was that the original scepter (called a heka) appears to have been wider and to have obscured part of the chin. Indeed, the portrait seems to have had all its pharaonic insignia retouched: The crown (or khepresh) and necklace (or wesekh) originally had quite different shapes. Martinez and his colleagues note that the original depiction more closely resembles a necklace style called a shebyu, which was common in royal portraits from the 20th dynasty, after the death of Ramesses II. The team speculates that this change could indicate that the tomb dates later than originally thought, after Ramesses II had become deified, and that the original depiction had been recognized to be anachronistic and was thus repainted. “A lot of this modern and theoretical reconstruction is, however, based on the usual archaeological guessing game that aims at filling the remaining blanks,” Martinez and the team say. “We remain clearly ignorant of what was really important and significant for the ancient Egyptian eye and mind.”

As was the case with the team’s imaging of the trace remnants of Egyptian blue and green, this pXRF method could also have the potential to help with reconstructing areas of these ancient tombs that have been damaged or weathered to the point that their murals are no longer visible, but which might retain pigment residues that could still be detectable. The researchers also hope to undertake a more systematic inspection of other tomb murals to try to characterize how common corrections were. “Due to the fact that most of the scientific inspections of these works of art have been carried out only through direct visual observation,” they say, “this may very well be but the tip of the iceberg.”

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.