This Article From Issue

July-August 1999

Volume 87, Number 4

DOI: 10.1511/1999.30.0

How the Laser Happened: Adventures of a Scientist. Charles H. Townes. 256 pp. Oxford University Press, 1999. $35.

Throughout his productive career, Charles Townes has contributed generously and with distinction to the boards, panels and councils of U.S. science policy and has mentored a veritable host of distinguished scientists. Moreover, for several generations, one's education in molecular spectroscopy has begun with Townes's touchstone in the field, Microwave Spectroscopy, co-written by Arthur Schawlow.

Townes's autobiography, How the Laser Happened, captures how an insight can spawn broadly applicable technology from basic scientific principles. It is, however, charitable to few. It is the practical writing of a practical man, and it is often bitter and deprecating of others.

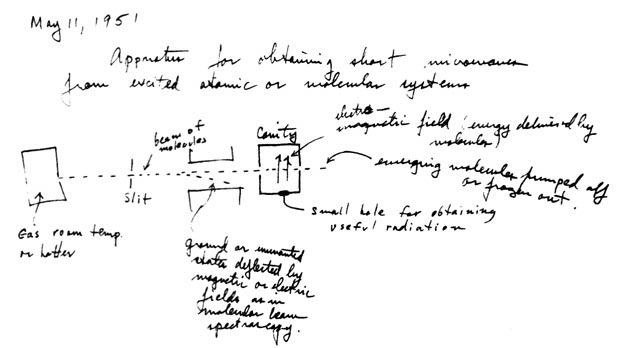

The 1964 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Townes with Nikolai Basov and Alexander Prokhorov for "fundamental work in quantum electronics which led to the production of oscillators and amplifiers according to the maser-laser principle." The first maser was made to work by Townes in 1954, using ammonia to produce coherent microwave radiation. This led various groups to consider how to produce an oscillator operating in the visible part of the spectrum, as was ultimately achieved in 1960: the progenitor of the now ubiquitous laser. Townes clearly prefers the clarity of his oral introduction at the ceremony for "invention of the maser and the laser." Inventorship, however, is a nebulous term, because all human thought stands on the shoulders of antecedents but for whom a particular thought might not have sprouted.

That some inventions are simply timely is an idea with resonance. Not here. Townes writes: "If Gordon, Zeigler, and [Townes] had not followed the path we did and made a maser, and if Schawlow and I had not gotten together, how long would development of the maser and laser have been delayed? My guess is not more than a decade or two." Historians of science pondering this very question for ages hence should consider this opinion.

From How the Laser Happened.

What about Basov and Prokhorov? "I personally have no doubt that they did come up with most of their ideas independently." (Emphasis added.) Results of others are most carefully attributed when they prove wrong. "Smythe [Townes's thesis advisor] went back through the data and prepared a paper, including my name as co-author, that said [incorrectly] the spin of carbon-13 is 3/2."

Regarding the development of 1.25-centimeter radar against his counsel, an unnamed "character in Washington" told him, "Well, you know, you may be right, but we've already made the decision, we can't stop now." Nobel Laureate I. I. Rabi is quoted as saying (about quadrupole hyperfine structure): "Charlie, that is a very pretty picture you are painting, but there is absolutely no science in it. There is just no scientific support for it." Rabi was wrong. Llewelyn Thomas, Niels Bohr and John von Neumann, all giants of physics, all deceased, are berated for being unable to understand the possibility of narrow-band laser oscillation. Regarding Gordon Gould, putative inventor of certain improvements to the laser: "Every time he learned I was doing something, he would dash to try and cover as much as he could think in his own notebook … [which] he had notarized at a local candy store." Jean-Paul Sartre declined the Nobel Prize for literature, but, according to this book, an unnamed member of the Nobel committee told Townes, "Well you know, he [Sartre] did write later and said he would, however, like to have the money!"

These are all textbook instances of hearsay, so the only way to make them a part of the historical record is to set them down in an autobiography. On the utility of history, Townes writes: "To ease [an interpersonal] problem, we [Joe Weber and Townes] published a joint account of maser history." Asked to be the science advisor on the Vietnam War, Townes demurred. "It would have meant moving with my family to headquarters in Hawaii, and put me in a position in which I could not clearly oppose the administration's policies in pursuing the war." On the Star Wars Strategic Defense Initiative: "It was an idealistic plan, and one that would keep the technical community busy. But I immediately had doubts." All the same, "I myself felt that some substantial effort was warranted."

This autobiography teaches one man's lessons from the life of science: "Throughout my career I have had to convince others, including sponsors, to let me keep following my own instincts and interests. Very often, this pays off." And, "A good scientist . . . must rely mainly and often stubbornly on his own judgment."—Samuel J. Petuchowski, Bromberg & Sunstein LLP, Boston

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.