Dinosaurs as a Cultural Phenomenon

By Keith Thomson

Why have dinosaurs gained such a hold on the public's imagination?

Why have dinosaurs gained such a hold on the public's imagination?

DOI: 10.1511/2005.53.212

Few sciences have been as successful as paleontology in remaining serious yet broadly accessible at the same time. Much of its popularity may come from the image of the paleontologist-explorer who pits himself against the wilderness and brings back fabulous things. The image is even partly true, because in the 19th century, dinosaurs (and paleontology) became part of the myth of the American West. No longer were important discoveries made by European gentlemen in suits and ties who directed a couple of workmen in an obscure quarry. Instead, fossil collecting had become "prospecting": A man with a horse and a pick—and of course a rifle—could venture out West and, like his gold-seeking cousins, bring back untold wealth from the rocks. That fantasy carries much more weight than the reality of the scientist in a lab coat, noting tiny details in endless trays of museum specimens and preoccupied more with statistics and geochemistry than with campfires in the badlands. No matter that most paleontology concerns undramatic taxa like graptolites and brachiopods, the field continues to enjoy a reputation as a richly rewarded, swashbuckling enterprise.

But why dinosaurs? They were not the first prehistoric creatures to gain wide attention. In 1801 Charles Willson Peale, a talented artist, showman, and inventor of the modern natural history museum, excavated the remains of three large mastodons from Newburgh, New York. The display of one of Peale's mastodons in Philadelphia helped start the public fascination with fossils. In the 1820s and '30s Mary Anning excavated an amazing array of ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs from the Jurassic cliffs of Lyme Regis, England. In 1824 William Buckland described the world's first dinosaur—Megalosaurus—and the next year Gideon Mantell followed with the herbivorous Iguanodon. An 1830 watercolor by Henry de la Beche first depicted such creatures in life settings, but to judge by popular science books of the mid-century, ichthyosaurs and pterosaurs were much more captivating to the public. The modern popularity of dinosaurs has partly to do with the creatures themselves; it owes even more to astute showmanship and media savvy.

Right from the beginning some dinosaur sleuths promoted their discoveries (and themselves) in ways that other fossil hunters did not (or could not). The anatomist Richard Owen, for example, featured them in a display at Britain's Great Exhibition of 1851. For this event, sculptor and master promoter Waterhouse Hawkins created life-sized reconstructions of dinosaurs, which were later removed to a permanent site in South London. Hawkins's famous dinner party inside a half-built Iguanodon moved paleontology a long way towards its modern cultural status.

In 1858, the first articulated skeleton of any dinosaur was found in a New Jersey clay pit. Waterhouse Hawkins traveled to Philadelphia to mount the new Hadrosaurus for Joseph Leidy (the leading paleontologist of the day) and then offered casts of it for sale to museums around the world. His mounted skeleton caused such a sensation that the Academy of Natural Sciences instituted admission charges to limit attendance.

The gentlemanly Leidy (once described as the last man who knew everything) was soon eclipsed by a group of well-funded scholar-adventurers who competed bitterly for some 30 years. Archrivals Othniel Charles Marsh at Yale and Edward Drinker Cope in Philadelphia collected thousands of fossils, including some 120 different dinosaurs, from the American West.

The story of Cope and Marsh is one of the great sagas of science, at turns funny, reprehensible and tragic, but there was no doubting their determination. In 1875, Marsh negotiated with the Black Hills Sioux for permission to collect on their lands and later became their advocate in Washington. In 1876, Cope collected specimens in Montana just a few weeks after the Sioux victory over the U.S. 7th Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, reckoning that "since every able-bodied Sioux would be with the braves under [their chief] Sitting Bull … there would be no danger for us." Yet neither Cope nor Marsh brought their work to the public, perhaps because they were too busy collecting and describing fossils and feuding with each other.

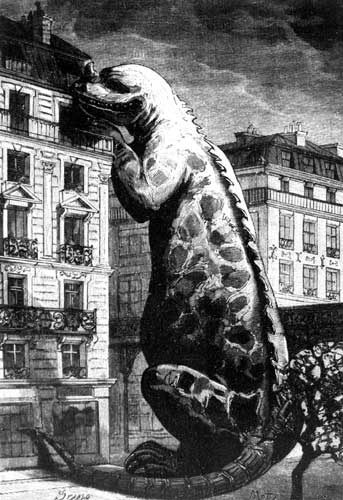

The key to modern dinomania may have been the discovery in 1884 of a whole herd of intact Iguanodon skeletons in a Belgian coal mine. Two years later, Camille Flammarion's popular book on Earth history, Le Monde avant la Création de l'Homme (or The World Before the Creation of Man), showed an Iguanodon in a theatrical pose: taking a meal from the "fifth floor" of a Paris apartment building (in France, the ground floor is the unnumbered rez-de-chaussee). Even so, it took a while for this sort of dramatic depiction of dinosaurs to catch on in the USA, until American newspapers followed in 1897 (American Century) and 1898 (New York World and Advertiser) with similar depictions of the far larger Brontosaurus against a backdrop of skyscrapers. The reception given to these fantastic images firmly established the potential of dinosaurs to capture public interest.

Cope suffered financial ruin later in life and sold his private collection to the American Museum of Natural History in 1895. The museum's director, Henry Fairfield Osborn (himself a paleontologist), made the dinosaurs a showcase attraction. The AMNH sent out Barnum Brown's 1902 expedition that bagged the first Tyrannosaurus rex. In the 1920s and '30s the museum sent a series of expeditions (not forgetting the movie cameras) to the Gobi Desert, led by the dashing Roy Chapman Andrews (the prototype for "Indiana Jones"). The original intent had been to search for early human fossils, but instead they made startling discoveries of horned dinosaurs and nests with eggs still inside. Not to be outdone, the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, with the financial backing of its eponymous founder, launched major efforts of its own, followed in turn by the other major museums, which bought specimens if they didn't mount their own expeditions.

Today the search for dinosaurs and other fossils spans the whole world, from the Arctic to Argentina, China to Greenland, Australia to Africa, and dinosaurs are big business. Publications on dinosaurs continue to multiply, from classics like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World, Karel Capek's satirical War With the Newts and Italo Calvino's Cosmicomics, to simple picture books. Giant fossil creatures (again mostly dinosaurs) featured centrally in Bill Watterson's classic comic strip Calvin and Hobbes—no shortage of literary allusions there. The fascination may have peaked with Michael Crichton's Jurassic Park (1990), which began as a book but became a blockbuster movie with two sequels. These films were the first to show dinosaurs in an authentic style with realistic behaviors. Since then, the BBC has gone a great deal further in its animated TV series Walking with Dinosaurs. In books, films, television, toys, computer games, newspapers and magazines—whatever is current—dinosaurs sell.

Granting the extraordinary marketing and publicity that surrounds dinosaurs , it remains true that unless they were fundamentally interesting, such efforts would surely have fizzled out by now. Part of the reason for their hold on our collective imagination may be that, of all extinct organisms, dinosaurs are the most paradoxical. On the one hand, dinosaurs were long believed to be clumsy and slow. They are extinct (with the exception of the bird lineage) and ought to be symbolic of failure. On the other hand, some (but not all) were big, strong and ferocious. As the largest-ever land animals, they symbolize power. The Sinclair Oil Company used a dinosaur as its logo. Compared with living behemoths such as elephants, rhinos or hippos, we mostly experience dinosaurs through reconstructions that are quite static. And until the advent of modern animation and computer-enabled reconstruction, dynamic representations of dinosaurs were far clumsier than the originals could ever have been; many (like the original Godzilla) were simply laughable. To see past these often inadequate depictions requires imagination.

As an old museum guard once told me, the secret of the fascination of dinosaurs, especially for the young, is that "they are half real and half not-real." The resulting tension gives them a particularly exotic nature. In the mind of a child, they are half dangerous and half safe, half scary monster and half special pal. They are powerfully strong but cannot reach us. They are in many ways familiar and near, and yet also very far away in time and totally foreign to our experience. Other extinct creatures, whether ammonites, trilobites, flying reptiles or mammoths, similarly fascinate us with their strangeness and antiquity, but they lack the same emotional connection.

Unlike a child's conception of the "real" world, which includes human and near-human monsters and living creatures like snakes and bugs, the world of dinosaurs can be wholly controlled in the imagination. With control comes power, which is wonderfully reinforced as children master (at surprisingly young ages) the special vocabulary of dinosaurs. The lexicon of dinosaur names is a closed world to parents (or they pretend it is) and therefore becomes a private world for the child. Some names—Tyrannosaurus, Stegosaurus, Iguanodon or Apatosaurus (children know it is no longer Brontosaurus)—roll off the tongue. Others, such as Eustreptospondylus, Archaeopteryx or Pachycephalosaurus are almost tongue twisters, but that is no barrier to a determined two-, three- or four-year-old. Surely this precocious, polysyllabic facility is an invaluable boon to cognitive development.

At a time when science (and especially evolutionary science) is not as fashionable or well taught as it used to be, paleontology is one of the most accessible sciences for children as well as adults. It does not require the mastery of arcane mathematics or bafflingly complex genomics, and discoveries in paleontology are usually identified with, and explained in public by, someone who speaks in layman's terms. Any amateur can have an informed opinion about mass extinctions, asteroid impacts and the age of the Earth. Paleontology, and especially dinosaur paleontology, is the single most accessible aspect of (embodiment of) the concept of evolution. This leaves us with one last question: What will we do if dinosaurs ever lose their appeal?

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.