Tugging at Hearts

By Robert Frederick

Proper heart-valve development requires cyclic mechanical loading.

Proper heart-valve development requires cyclic mechanical loading.

DOI: 10.1511/2016.122.269

To watch hearts develop, biomedical engineer Jonathan Butcher of Cornell University pioneered a method in 2010 to grow chicken embryos outside of their shells. Since then, his lab members have cracked open thousands of fertilized eggs, carefully placing three-day-old embryos into egg-shaped hammocks made from clear plastic film.

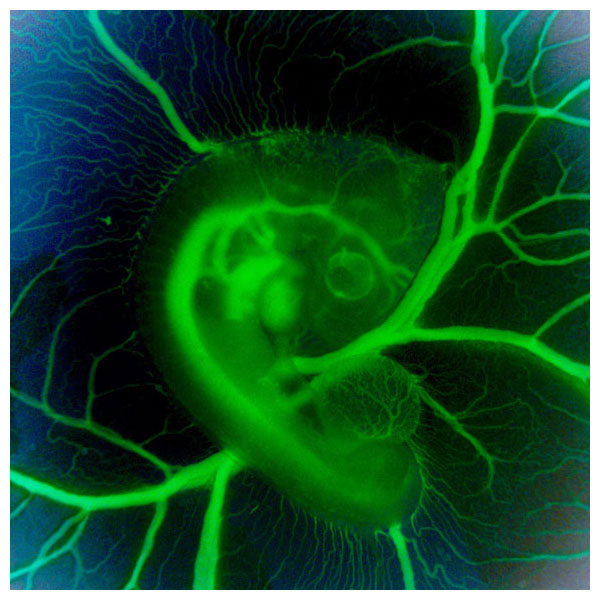

“We needed to be able to transport these embryos between imaging technologies,” says Butcher, who studies the embryos until day 10—about half of gestation—imaging them optically (above) as well as with ultrasound and a three-dimensional X-ray method called microcomputed tomography.

Butcher’s research focuses on the development of heart valves, marvels of evolution’s biomechanical engineering that ensure blood flows in only one direction.

“Only about 10 percent of the clinical problems we see in kids born with heart-valve defects have to do with known genetic mutations, so there’s a real need to understand what else can bring about these developmental anomalies,” Butcher says.

Researchers routinely color blood with green fluorescent dye to better see how the blood flows. In one of Butcher’s experiments, his team found that by partially closing off blood vessels to alter the blood flow’s force, they could boost or limit how much the valve progenitor cells developed—from a globular cushion shape to the thin leaflet shape needed for a proper valve.

“There’s certainly continued open questions with respect to how all of that is occurring,” says Butcher, whose team also published in Current Biology earlier this year about how the heart’s cyclic constriction regulates the set of molecular switches involved in the valve’s proper development, “but this is what our current work is exploring.”

That exploration means a lot more chicken embryos growing in plastic hammocks: Butcher says his team cracks open dozens each week.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.