This Article From Issue

January-February 2000

Volume 88, Number 1

DOI: 10.1511/2000.15.0

Thoreau's Country: Journey Through a Transformed Landscape. David R. Foster. 240 pp. Harvard University Press, 1999. $27.95.

The Hidden Forest: The Biography of an Ecosystem. Jon R. Luoma. 228 pp. Henry Holt, 1999. $22.

Natural-history writing is often long on nature and short on history, given our limited understanding of how landscapes have been disturbed, modified and restored in the past. This lack of perspective hampers environmental planning, particularly by American forest managers.

Now two new books provide two very different histories of forest research, each valuable in its own way.

Foster's Thoreau's Country is an intriguing surprise, relating how Henry David Thoreau, author of Walden and pioneer ecologist, "lived at a time when the New England landscape was arguably the most tamed and most dominated by human activity in its entire history." The author, who is director of the Harvard Forest, explains how trees have since colonized abandoned farms. As a result Massachusetts today has a higher percentage of forest cover than Oregon.

Luoma's The Hidden Forest is quite different: a contemporary history of how Pacific Northwest forest ecologists came to change our view of that region's virgin old growth from "decaden" and in need of harvesting to "complex" and worth saving, a shift that resulted in a sharp reduction of old-growth logging in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

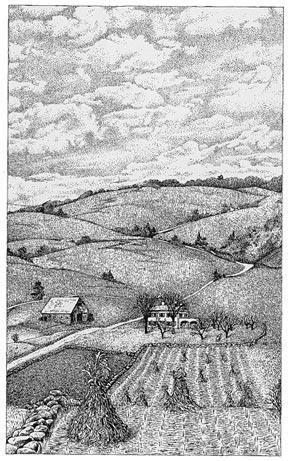

From Thoreau's Country.

It weaves this story of evolving research, centered at the H. J. Andrews Experimental Forest near Eugene, Oregon, with lucid and entertaining explanations of ecological complexity.

Both books are recommended. Both also left this reviewer wanting more: bolder conclusions by Foster on the meaning of New England's forest renaissance and a more balanced and deeper assessment by Luoma of "new forestry" experiments that seek to let us have our forest products and forests too.

Foster first. Thoreau's Country is as much about culture as biology, and more about our perception of nature than nature itself. It is thus a disappointment that the author fails to provide an incisive biographical background sketch of Thoreau: How the devil did the old boy get so much time to analyze his neighborhood? That complaint aside, Foster—by expertly excerpting from the icon's two million words of journal entries—shows us a thinker who was a brilliant journalist, observant naturalist and eloquent writer.

Thoreau's observations alternate with Foster's of the remarkable comeback of the New England forest landscape today.

The book's descriptions of 19th-century life and landscape are fascinating. Here is a slowly industrializing New England of dense, intensively managed farms, frequently clear-cut wood lots and vanished wildlife in which Thoreau the nature lover is an eccentic, a minority of one.

The famed naturalist never ventured far from his Concord neighborhood and never felt a need to see the great wilderness of the American West. His Walden Pond was a cut-over lake, that century’s cultural equivalent of today's suburbs.

"It is in vain to dream of a wildness distant from ourselves," Thoreau justified. "There is none such. It is the bog in our brain and bowels, the primitive vigor of Nature in us, that inspires that dream. I shall never find in the wilds of Labrador any greater wilderness than in some recess of Concord."

Indeed, Thoreau found in fragmented wood lots enough clues to piece together a prediction of forest succession that has played out since his death in 1862. Farms were abandoned for factory jobs, trees came back and wildlife has followed. It is not the primeval forest the Indians managed by fire, nor Thoreau's woodlots but rather the latest transition. Its lesson?

"If we set out with the expectation of protecting and preserving any landscape as it is today, we are certain to be frustrated for it will inevitably continue to change," Foster warns. "If we seek to recreate 'natural' features of our landscape, we need to understand the processes that formed them in the past"—human history and natural catastrophe. From the vantage point of Harvard Forest, wilderness is not a natural absolute but a human idea, and nature is bound up with human culture.

This is a notion that has been gathering steam for more than a decade, modifying the old environmentalist ideal of "God's Country: Please Keep Out." Nature, dang it, is not frozen like a Sierra Club poster.

Although Foster's argument is fine as far as it goes, this reviewer couldn't help wishing for a more sweeping prescription. Does New England’s history mean we can relax, then, because wounded landscapes cycle and recover? Is human manipulation not just inevitable but to some degree desirable? Is Thoreau's intensively farmed Massachusetts, sounding as idyllic as a Currier and Ives print, as valid and pleasing as the forest that has succeeded it? To cut, or not to cut?

Foster deserves credit for not wringing more glib solutions out of Thoreau than his research can bear. Still, one wishes for a sharp sequel that would be a 21st-century journal of the evolving New England landscape as descriptive, eloquent, opinionated and cantankerous as the elf of Walden Pond.

Luoma's Hidden Forest comes at trees from 3,000 miles away and an entirely different tack, focusing on recent preservation of the uncut remnant of a gigantic, magnificent forest ecosystem.

His story of Northwest forest ecology and a revolutionary shift in regional perception toward old growth has been told before. But by concentrating on the science side of the story, Luoma presents the most comprehensive account yet of how the research developed. The contributing editor to Audubon Magazine does a splendid job of weaving together scientist and discovery, organism and relationship, into an organic whole. He is particularly adept at making forest biology come alive, from the miracle of tree construction to the tree’s symbiotic marriage with fungi. Anyone seeking to understand the value of these forests—or a textbook example of influential basic research—would do well to start with Luoma's book.

Don't end with it, however. This reviewer knows and is an admirer of the ecologists that Luoma profiles, but you would hardly guess from The Hidden Forest that their views and remedies remain controversial, even in their own academic departments. Although there is consensus on the ecological complexity of Northwest forests, resulting in a drastic reduction in U.S. Forest Service logging on federal lands, debate and uncertainty remains on how to apply the new findings to timber management.

Accordingly, this is an advocacy book for preservation—three cheers for its strong and eloquent point of view—but it is also unbalanced. The author does not address or defeat the arguments of industrial foresters, but simply ignores them.

Complaining that even "new forestry" logging looks ugly, Luoma blandly concludes that best thing for these forests ecologically and aesthetically is not to cut them at all. Well, yes, and the public has made that decision for millions of acres.

But what about society's demand for wood and paper, or the three-quarters of the Northwest forest already managed for timber production? How do we apply this new ecological information to wet, steep, brushy and fire-prone land still routinely clear cut for a number of biologic and economic reasons?

There is little evidence in Luoma's "selected reading list" or his text that he read or interviewed industry scientists at all. The result is an environmentally correct book that uses the new science only as an argument for preservation and thus falls short of bridging the gap between the ecologist and the tree farmer. That's too bad, because the preservation battle has been largely resolved: The vast majority of these forests are either already protected or already cut. The Northwest issue in the 21st century is going to be management of tree farms, second growth, urban greenbelts, sprawl, back yard wildlife habitats and suburban salmon streams. In other words, people in the woods.

These two books thus make a terrifically thought-provoking pairing. Here is Thoreau, lamenting the loss of nature even as the technological changes he condemns will ultimately result in farm abandonment and a New England forest comeback. Here are modern ecologists such as Fred Swanson, Jerry Franklin and Chris Maser at the other end of the nation but in Thoreau's point of time, racing to understand and save a threatened ecosystem. History as a wheel, but turning at different rates in different places.

In reading these books, one realizes that a modern forester can be a time traveler in the United States, jetting to forests at very different stages of harvest and recovery. Our east-to-west historic pilgrimage grants remarkable perspective. Synthesizing that perspective into a public consensus on forest preservation, renewal and resource extraction is work that is just beginning, however.

The good news is that the underlying message of these two books is hope. It is heartening that science can change our view of something so broad and basic as a forest, as it did in the Pacific Northwest. And reassuring that forests can recover from near-extinction, as is happening in New England.

American forestry has been plagued by arrogance, opportunism, expediency and greed for three centuries. Books like these point to a possible future of caution, appreciation, patience and balance in the century to come.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.