This Article From Issue

January-February 2003

Volume 91, Number 1

DOI: 10.1511/2003.11.0

The Fate of the Mammoth: Fossils, Myth, and History. Claudine Cohen. Translated by William Rodarmor. xxxvi + 297 pp. University of Chicago Press, 2002. $30.

This is not a book about mammoths," declares Claudine Cohen in the introduction to The Fate of the Mammoth. Her true subject, she explains, is the history of paleontology. The mammoth is the icon she has chosen to trace the mythic imagery and early scientific inquiries that led to modern understanding of extinct species.

The Fate of the Mammoth was originally published in French in 1994. Cohen, a historian of science, has written a new preface for this English translation, listing recent publications in the history of paleontology and new scientific discoveries, including cloning developments that may someday bring a mammoth to life.

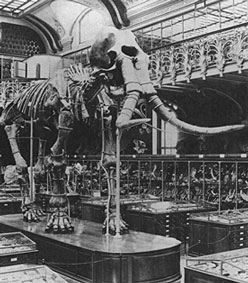

From The Fate of the Mammoth.

It's an inspired choice. Mammoths, the ancestors of modern elephants, interacted with humans until the extinction of Pleistocene megafaunas about 10,000 years ago. Fossilized remains of mammoths litter the globe, each new set of colossal bones evoking keen interest when it comes to light. Woolly mammoth carcasses found in the arctic permafrost are so well preserved that we can picture them alive. We are awed by their massive, shaggy bodies and heavy, curved tusks. And yet, perhaps because we can imagine their tragic demise in ice and snow, we see them as vulnerable and pitiable. The mammoth thus makes an excellent mascot for a tour through modern paleontological history.

The logic behind the book's organization is hard to discern, but each chapter is absorbing. The historical and scientific material is presented in an informal, speculative style that should engage readers across disciplines. The illustrations range from prehistoric cave paintings to scientific drawings and modern cartoons.

Part One, "Images," begins with the discovery of a frozen mammoth in Siberia in 1799. Cohen's account of attempts by artists, novelists, filmmakers and scientists to reconstruct the mysterious creature demonstrates how difficult it was, and still is, to recover with certainty the appearance, behavior and surroundings of even well-preserved extinct animals.

In Part Two, "Myths," Cohen cites a few ancient Greek and Roman sources as the earliest examples of the idea that mammoth fossils were the remains of giant humans and were thus proof that human beings had diminished in size over time. But she is more at home with the lore of giants during the Middle Ages and Renaissance, when mammoth fossils were displayed in cabinets of curiosities or revered in churches as the relics of saints.

Early in this section, Cohen explores the affair of the "giant bones of Teutobochus." In 1613, huge fossil remains found at Dauphiné were publicly displayed as the bones of a giant Germanic king of the Roman era. The relics were hotly debated for the next two centuries. Cohen's account opens a window into the paleontological thinking of the era, during which plausible historical explanations began to replace mythical giant lore. For example, Jean Riolan thought the Dauphiné bones might be those of a marine monster or an elephant, perhaps brought there by Hannibal's army (a theory debunked by Georges Cuvier on historical-statistical grounds). A tooth from this set of remains was positively identified in the late 20th century as having come from a Dinotherium, a primitive proboscidean.

Another chapter describes the fanciful reconstruction of a mythical unicorn from mammoth and other fossils. Here Cohen shows how the natural philosopher Leibniz and others anticipated formal theories of extinction in recognizing that fossils were organic remains of ancient life-forms rather than miraculous "sports of nature."

Cohen assumes (as do conventional histories of paleontology) that mammoth fossils have been featured in legends, fables and histories of the earth for only about three centuries, and that the mammoth became a "massive, continuous presence in Western knowledge" only at the end of the Renaissance. This standard scientific assumption, also articulated by the late Stephen Jay Gould in his foreword to the book, bypasses the evidence that mammoth fossils were objects of much interest in antiquity and consigns all prescientific interpretations of them to the realm of superstition, retrojecting medieval concepts back into classical times. As Cohen shows, Cuvier countered the medieval fossil fables in 1796, demonstrating that mammoths were an extinct elephant species wiped out by some catastrophe. But the ancient Greeks had come to a similar conclusion two millennia earlier. How those classical insights (which Cuvier himself built on) were lost during the Middle Ages remains a puzzle.

Part Two includes the intriguing, little-known story of the flourishing trade in mammoth ivory in Siberia and China. Cohen supplements this material with folklore of the Yakuts and other arctic people (who believed that mammoths were large, burrowing monsters who died when they saw sunlight), anecdotes about the recovery of great behemoths buried in ice, and myths and early geological theories that attempt to account for the fossil record (for example, the biblical Deluge). She also explains how religious faith and reason diverged as scholars began to formulate laws of nature.

Surprisingly, one important "fate" of the mammoth goes unmentioned: Their petrified bones and tusks were ingested as medicine. Pleistocene fossil material continued to be used in medicine into the 18th century in Europe; apothecaries eagerly attended excavations of mammoth skeletons to gather bones and teeth to pulverize into healing infusions, and many kept a mammoth tusk chained to the counter for scrapings.

In Part Three, "Stories," Cohen paints a panorama of changing concepts about mammoths in Western culture. The animals played a role in early American nationalism. Thomas Jefferson was intensely interested in the possibility that some were still alive, and he collected Indian legends that identified fossilized mammoths as extinct giant ancestors of the buffalo. This tantalizing Native American interpretation seems fairly advanced; Cohen's brief treatment of it leaves the reader wishing for more.

Mammoth bones from North America generated exciting studies in Europe, culminating in Cuvier's theories, to which Cohen devotes a chapter. Next she recounts the progress of the mammoth through Victorian England, concluding with Darwin's theory of evolution. In the 19th century, controversies about the mammoth involved "high philosophical and religious stakes," as humanistic, scientific views vied with biblical creationism over man's true place in the natural "burgeoning of species." Cohen sets out the vigorous debate over the question of the antiquity of human beings and our relationship to vanished megafaunas.

In Part Four, "Scenarios," Cohen begins by describing how scientists have sought to place mammoths in the various evolutionary trees of life (from Darwinism to punctuated equilibrium and beyond). Then she returns to narratives about mammoth fossils in Africa and Alaska (oddly neglecting South American mammoths, which were well known to Cuvier). Next she projects the destiny of the long-extinct mammoth into the future, with a stimulating discussion of efforts to extract DNA from frozen mammoths to clone a living specimen. The last chapter deals with scenarios for the Pleistocene extinctions, from climate to human overkill. In a provocative Conclusion, Cohen links the fate of the mammoth to the destiny of paleontology itself.

By harnessing her narrative to the extinct but still vigorous mammoth, Cohen has created a nuanced and complex tableau of medieval fossil lore and the fitful progress of paleontological science. She has done an admirable job of reanimating the woolly mammoth in all its legendary and scientific glory.—Adrienne Mayor, independent folklorist, Princeton, N.J.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.