The Tales We All Must Tell

By Robert Chianese

Public confessions of misdeeds against nature can inspire environmental awareness, commitment, and action.

Public confessions of misdeeds against nature can inspire environmental awareness, commitment, and action.

DOI: 10.1511/2016.121.212

As I crossed the channel from Ventura, California, to Channel Islands National Park on a misty morning a year ago, I recognized that our excursion boat captain had once been my fishing boat captain on the same waters. I approached him and asked whether he had given up fishing. He said he had, and explained why:

I just couldn’t watch all that waste. Nice people out for a day of fishing kept bringing in more and more fish they didn’t need just to feel they had a good day. Some fishermen gave away extras to others so they could go on and hook and fight and reel in more without going over limits.

I understand that, I said. I did that too, when we had a good run. I would keep the biggest ones and give smaller ones away. That was rather sneaky. The captain continued:

I didn’t mind that so much, but when in certain seasons we came into a run of jumbo squid, the huge white Humboldts, then the waste was too much. Few people took them home, so when it was over, the crew and I were left with a boatload of them covering the whole deck, sometimes two deep, with not one person taking even one home. Every day this happened I tried to shut the fishing down, but the thrill was too great. The sport was lost in wasting these animals.

I kept it up for a while, but then I saw we were taking too many of all fishes. Fewer and fewer were full-size, even though we stayed within limits. I made sure of that. Still, I had had it, those boatloads of jumbo squid. I stopped fishing.

What was most striking to me about the captain’s story was the way he decided to quit. Not because of a regulation. Not because of being lectured or shamed. He did it on his own, in a way that made perfect sense to me. Indeed, I had myself given up fishing for very similar reasons.

Much of the modern environmental movement may rest on the words of transformed offenders.

Far more often, though, we remain stuck in our behaviors, often completely ignoring their consequences. Every day, we commit assaults against the environment, both large and small. I am not pointing fingers. I do it, too: I still eat meat, including fish; I bought a new hybrid but have an old truck for fun (a case of flash over efficiency); I walk for exercise, but could do errands that way too; and as a drought-conscious Californian I should empty every full drain bucket from our kitchen sink outside on our plants, but I don’t—too lazy for such water-saving efficiency each time, I guess.

Collectively, these acts have profound consequences on a global scale. Scientists warn that we are already experiencing some of the effects of human- induced global climate disturbance, such as melting glaciers, rising sea levels, and an increased frequency of extreme weather events. We are in our “sixth extinction” period on planet Earth, with the speed of extinctions estimated to be 100 times faster than before modern humans entered the picture. And yet we don’t see a public alarmed and motivated to remedy the global catastrophe we are engineering. Do we need more statistics, more fact-based warnings, more climate science, more news coverage?

I suggest we try a new tactic to inspire the public to take action: Make it personal. The boat captain’s brief recital of what happened to him is a personal confession. It moved me because of the teller’s transformation from gung-ho fisherman to sober environmentalist, all of it conveyed in his tone as much as through the story itself. He wasn’t preaching but telling a former customer what had changed him, and the brief rapport between us indicated we understood each other. That was a closeness I didn’t anticipate, and I should have volunteered my own story of becoming disturbed about wasting our precious ocean resources.

Such stories have a way of drawing us in, tying us to the specifics of the character and the situation in a way that media coverage of abuses against nature often does not. Hearing stories of personal confessions of transgressions against nature can prompt others to reevaluate their relationship to the natural world, perhaps reflect on mindless damage that they may have caused it, and, in some cases, seek ways to atone for the act.

The poet and writer can teach us how to make stories of environmental transgression personal and persuasive. Poetry, literature, drama, and other disciplines within the humanities are built around stories that produce immediate emotional impacts. These art forms frame issues of life and death and everything in between in personal terms. They place specific characters at the center of terrifying human conflicts and allow us to watch them twist, turn, and suffer the pains of avoiding their own collision with the conflict. A crisis often crushes the characters but can break them open to self-acceptance and wisdom—for them and vicariously for us.

There is perhaps no better model for confessing an environmental abuse than Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” Although a 200-year-old poem may seem like an unlikely place to find inspiration for a modern environmental movement, Coleridge’s tale is an excellent example of how to make a moving confession of an environmental misdeed.

This early romantic period poem from the famous volume Lyrical Ballads (1798) follows the life path of someone who violates the natural world. The mariner’s shipmates befriend an albatross, which they believe brings a wind that drives the ship out of the frigid Antarctic. The mariner shoots it with a crossbow, thoughtlessly. Then an ensuing intense heat and lack of rain afflict the crew, and they hang the albatross around the mariner’s neck, blaming his act for the stasis and high temperature. (To this day, an “albatross” remains a metaphor for a guilty transgression one cannot remove—a testament to the power this poem still carries centuries after it was written.)

The whole crew drops dead, so that the mariner is “Alone on a wide wide sea!” At night the isolated mariner notices luminescent “water-snakes” flashing colors, and becomes entranced by their beauty and blesses them, again “unaware.” Whereupon the albatross falls from his neck into the sea and it rains buckets. We are only halfway through the poem, but we can look ahead to the conclusion and its succinct homiletic moral of radical biophilia that redeems the mariner: We need to love “all things both great and small” for our own health and survival.

The mariner spends the rest of his life as an itinerant confessor and manic recruiter for his vision of nature. We hear his tale as he retells it to an anonymous guest on the way to a wedding. The guest ultimately does not attend the wedding; he leaves stunned, contemplating what he has just heard from the madman storyteller. Apparently he needs time to recover before he resumes his participation in society and its cultural traditions, such as marriage. He may not go off on an expedition to save albatrosses, but he may ask himself if he loves all creatures great and small. Such is the effect of powerful stories of personal transgression and transformation.

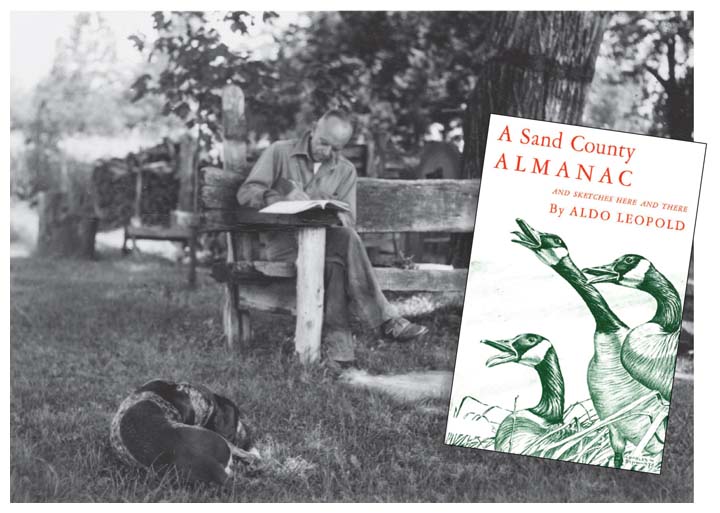

Many modern-day environmental writers have employed similar storytelling strategies to confess publicly their acts against the natural world. In the 1949 book A Sand County Almanac: And Sketches Here and There, which sold more than two million copies and helped establish the modern conservation movement, renowned ecologist Aldo Leopold described how he once “pumped lead” into a playful pack of wolves “with more excitement than accuracy,” and then came to a new appreciation of the importance of each interconnected creature in an ecosystem. In the 1991 book Second Nature, popular journalist Michael Pollan described how he became obsessed with eradicating a woodchuck from his garden, which, he confesses, “put me in touch with a few of our darker attitudes toward nature: the way her intransigence can make us crazy, and how willing we are to poison her in the single-minded pursuit of some short-term objective.” By telling their stories, environmental writers have inspired others to reflect on their own transgressions. Indeed, much of the modern environmental movement may rest on the words of transformed offenders such as these.

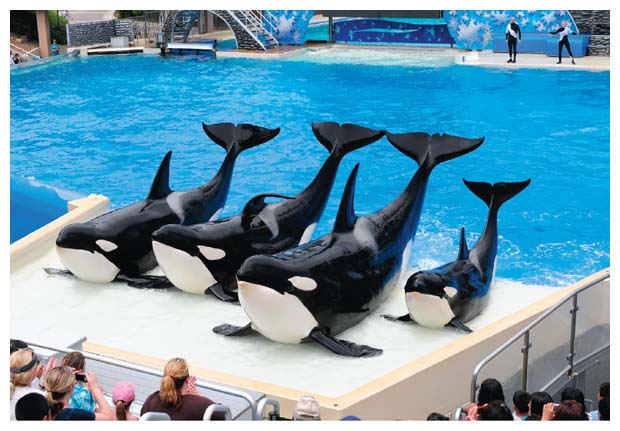

Documentaries are powerful modern platforms for storytelling. These films have helped inspire the public to push for environmental regulations, including better protection of animals such as elephants and great apes. In one present-day iteration of Coleridge’s mythic investigation of humanity’s relation to nature, the documentary Blackfish (2013) captures the shift of consciousness of many SeaWorld trainers about the cruelty of confining killer whales to tanks and the dangers these whales can pose to the staff.

Much of the film centers on the killing of Orca trainer Dawn Brancheau in 2010 by the whale Tilikum. SeaWorld announced the death as “an accident” resulting from Brancheau’s supposed mistake of allowing her ponytail to dangle in the water, which the whale used to drag her under during a performance. This account of the “accident” was exposed as a lie by trainer Linda Simons, who lost her job for going public with information about poor training and dangerous whales at SeaWorld.

But it took several years and the personal confessions in Blackfish to set the record straight (the water park publicly contests some of the information in the movie, so controversy remains). Blackfish revealed the lingering self-imposed silence of the trainers, who felt loyalty to the whales and wanted to protect them. Many trainers did not at first acknowledge that simply by training and performing with the whales, they were committing their own transgressive acts. In the film, their realizations of culpability finally get released through open, tear-filled, seemingly real-time confessions. The trainers also express anger at members of management who lied for so long after almost all the trainers had come clean about the real condition of the whales born, kept, and trained in captivity.

In a final turnabout that parallels the mariner’s story, SeaWorld will transform itself into a protector and conservator of all marine life. It announced this year that it will phase out all orca shows over the next few years, and stop breeding the animals in captivity. In addition, along with the Humane Society of the United States, SeaWorld pledges to “actively partner in efforts against the commercial killing of whales, seals, and other marine mammals, as well as end shark finning.” It also commits itself “to protect coral reefs and marine species that inhabit them….” If it follows through on these commitments, SeaWorld will have a different tale to tell as it becomes a public voice for ocean creatures great and small.

Social media are the newest platforms for storytelling and may be the most promising ones yet for inspiring environmental action through personal confessions. For one, they come with a massive audience. According to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center, as of January 2014, 74 percent of American adults with Internet access used social networking sites. Social media also have a proven record of generating support for a wide range of causes, from the political to the personal. And, importantly, social media have a long history of encouraging public confessions. Tumblr has a “postcard confessions” feature that could be employed for environmental confessions. Facebook users have created many confessions pages; often such announcements are for social uses, such as admitting romantic crushes, but similar pages could be created to post collections of ecological violations and their aftermaths.

We could also blog about our environmental missteps. I created a blog titled Eco-Confessions (http://ecoconfessions.blogspot.com/) where I invite all those interested in this subject to share their stories of environmental transgressions and realizations. My own confession is the leadoff post:

In my boyhood I roamed the New Jersey woods next to our modest postwar suburb. The woods provided every adventure in its remaining forest, swamps, and creek. Some older boys fished, trapped, and hunted, while my pals and I explored the place as very unconscious “naturalists.” We brought specimens home in jars, boxes, and bags. And we threw stones, a favorite pastime, at lots of things. One day I lobbed a large one at a blue jay and it landed square on its back, flattening and killing it. None of us rejoiced at that. It was a terrible violation and a warning about careless pursuits.

Then we built slingshots, strong ones out of plywood, with real Wham-O rubber bands and copper BBs for ammunition. I could have gone after birds, or easily penetrated the shells of turtles sunning in the ponds, but I didn’t. The memory of the squashed innocent blue jay kept my reckless animal-killing ardor in check. I take my shift of consciousness about respecting all things great and small from that early transgressive act and the remorse I felt thereafter. I may be an environmentalist because of it.

We, like Coleridge, need to find a confessional voice and share it in whatever medium is readily available, even if that is a face to face conversation—or a poem.

The former fishing boat captain who led my trip to the Channel Islands teaches visitors about the importance of protecting the animals he once overfished. “In some way, I am making up for all that taking and waste,” he told me. “If I can educate people on the rides out and back about the need to support this fishery by being careful to use what they might catch or to leave it all alone, letting it take its time to replenish, then perhaps I’ve made up a bit for too much waste.” But when I asked him whether he’s considered sharing his own story with visitors, he replied, “No I haven’t. They didn’t come for that.”

The need for environmental action is too pressing for us to wait any longer for an audience to come to us for our confessions. These stories are the missing element in society’s disregard of the analysis and warnings of scientists, ethicists, and humanists alike about our biocidal mania. If we all reach out and share our stories using whichever platform works for each of us, we can learn from each other and usher in a new age of environmental awareness, concern, and action. The move from personal violation to personal responsibility and public discussion is the mariner’s story. It also should be our own.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.