This Article From Issue

May-June 2025

Volume 113, Number 3

Page 185

ME, BUT BETTER: The Science and Promise of Personality Change. Olga Khazan. 288 pp. Simon Element, 2025. $28.99.

Can someone change their personality? That question lies at the heart of Olga Khazan’s newest book, Me, But Better: The Science and Promise of Personality Change. Khazan documents her attempts to alter her personality and become happier over the course of one year. Psychological research shows that personality does change for many people, but usually as a result of biological processes such as brain maturation or social changes such as new roles (for example, becoming a parent or starting a career). Khazan became motivated to try changing her personality after taking a personality test that showed her combination of traits were correlated with unhappiness and dysfunction. Tired of feeling “neurotic, introverted, and disagreeable,” she set out to alter her personality.

Original: Anna Tunikova for peats.de and Wikipedia Vector: EssensStrassen/CC 4.0

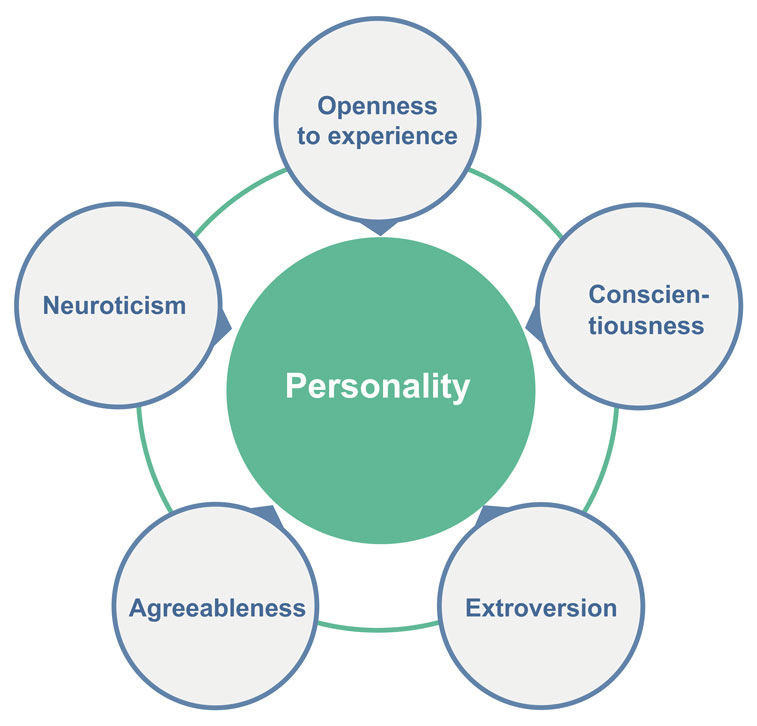

Personality is thought by some to be made up of specific traits known as the “Big Five”: neuroticism, extroversion, agreeableness, openness to experience, and conscientiousness. Taken together, levels of these traits are said to predict how a person will respond to situations.

Khazan opens the book with an exploration of what personality is, followed by a chapter on how personality changes. Then she dedicates a chapter to each of the Big Five before coming to conclusions about her year of personality change.

Before starting her project, Khazan consulted various academic experts on personality development and trait change, along with some nonexperts best described as self-help coaches. “The best personality-change interventions help people figure out what they want to change, tell them how to change, and remind them to continue changing,” she writes. Khazan states early in the book that personality change might simply be a matter of remembering how you’d like to be and then acting that way—consistently. She then sets out to change her personality by focusing on each of the five traits for a few months, starting with extroversion.

After initially scoring “very low” on extroversion, Khazan decides to start her journey by trying something that would force her to leave her house and be social. Improv comedy is the first thing she settles on, because improv forces participants to interact and just say something in response to the other person. She then joins a sailing club and realizes that socializing in person provides the real-life interaction and contact she hadn’t known she was missing, despite interacting with others all day on the computer. Later, at a party she decides to host, she realizes that, although she may be doing many of these things for the book, they also simply make her feel good. By the time she retakes the introversion section of the personality test at the end of the first part of her project, her score has gone up to “about average.”

From there, Khazan tries a wide variety of other activities for the remaining traits, such as workshops on how to be a better conversationalist, a sensory deprivation tank, yoga, different kinds of meditation, and even surfing lessons. Some strategies Khazan tries seem questionable at first blush (such as using the drug MDMA (3,4- methylenedioxymethamphetamine, also known as ecstasy), whereas others are more established, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, which has almost 60 years of strong empirical support for its effectiveness. (By contrast, in the summer of 2024, a United States Food and Drug Administration advisory panel declined to approve MDMA-assisted therapy for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder.) Indeed, the activities Khazan chooses to participate in during her year of attempting personality change vary widely. In addition, she appears to give equal weight to both scientists who study personality change and untrained entrepreneurs who hawk untested, unvalidated techniques.

Still, the book shines whenever Khazan weaves her refreshingly honest tales of her often entertaining attempts at personality change into the narrative. Through sharing her personal and family history, as well as her experiences being a woman in America, she reveals a great deal about her inner fears and anxieties, expresses her vulnerabilities, and puts her experiences out there for all to see, making for a relatable narrator.

Khazan acknowledges that personality change requires sustained hard work and an ability to do things that make one uncomfortable: “But month after month, I dreaded the highway, or the improv showcase, or the stressful situation du jour, and ran into it anyway. This is what personality change looked like in the end: fits and starts, with the goal being for the starts to outnumber the fits.”

The self-experiment in personality change laid out in Me, But Better is something very few professional personality researchers (including myself) would try on their own, and for this Khazan deserves praise. Ultimately, she comes to the conclusion that achieving large-scale change is not realistic, and instead she is satisfied by small but noticeable improvements. She wanted to reduce her neuroticism, which previously caused her large amounts of fear and anxiety. Although her core trait levels are still mostly where they were at the beginning of the experiment, they are altered in slight but important ways that make her life healthier and happier, such as not using alcohol to cope with anxiety. Though fear and anxiety are still present, her responses to these feelings and stressors have changed.

By the end of her endeavor, Khazan asks a question that many personality development researchers have asked in recent decades: How deep and lasting are the personality changes many of us work hard to make? Khazan’s attitudes and behaviors did change over a year, at least based on her personality test scores, but does that qualify as a “new personality”? The personality changes that Khazan tried to produce—dramatic alterations that occur over a short period of time—rarely last. The transformation may look profound on the surface, but our inner selves may not have transformed much at all. Khazan herself considers this possibility near the end of the book: “Is it real, or is it all an act? Does a person’s changed behavior mean they’ve truly changed? Or if it requires continual effort, does it mean they haven’t really? And does it matter?”

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.