This Article From Issue

January-February 2001

Volume 89, Number 1

DOI: 10.1511/2001.14.0

Genome: The Autobiography of a Species in 23 Chapters. Matt Ridley. viii + 344 pp. HarperCollins, 2000. $26, hardcover; $14, paper.

We are at a unique confluence of science and publishing in which the results of the former are being dispersed by the latter at such a rate that even the most ardent reader of popular science books can hardly keep up. This is good news for science, of course; its products are outstripping even Moore's law of doubling every 18 months, so updates and revisions are called for just as frequently. Luckily for publishers, readers are willing and able to plunk down a quarter of a hundred bucks to discover the secrets of life and the cosmos. Literary agents specializing in science tomes are demanding—and getting—five- and six-figure advances for their clients, and by most counts publishers are earning back those advances in a matter of months.

From Genome.

British science writer Matt Ridley is a participant in and beneficiary of this pleasant conjuncture, and he has rewarded his readers admirably with such biobestsellers as The Red Queen: Sex and the Evolution of Human Nature and The Origins of Virtue: Human Instincts and the Evolution of Cooperation—the latter being, in my opinion, the most readable book to date on evolutionary ethics. In Genome Ridley continues his expansion into larger themes, as he takes us on a roller-coaster ride through the very foundation of life: DNA. The carnival-ride metaphor is apt, because in Genome Ridley hits many highs and lows (depending on the complexity of the subject and his knowledge of it) and leaves the reader feeling a little dizzy at the end. The fault, on one level, is not Ridley's, as he has taken on a subject vastly deeper and more complicated than can possibly be covered in a single volume—any one of the 23 chapters could have been a book in itself. And he has succeeded in providing a highly readable and informative encapsulation of the science that promises to do for the 21st century what nuclear physics did for the 20th. A revolution is in the making, and Ridley has his finger on its pulse.

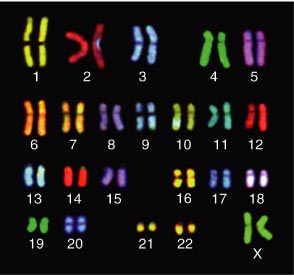

Ridley's technique is at once clever and delimiting: Each chapter represents a chromosome, for which he has chosen a single entity supposedly determined or influenced by that chromosome. For example, there are chapters on intelligence, instinct, self-interest, disease and stress—entities that he associates with chromosomes 6 through 10, respectively. It is a facile literary device to help readers get their minds around this illimitable subject, but I fear that it gives the wrong impression—Ridley's disclaimers notwithstanding—that such things as intelligence, instinct or self-interest are wholly located on a single chromosome and are therefore genetically programmed and biologically determined.

I sometimes wonder, only half in jest, if there isn't a metagene gene—a gene that causes people to think that everything is in our genes. Evolutionary psychologists could have a field day with the concept. Of course, Paleolithic cavepersons knew nothing about genes, so we must postulate that they tended to view the actions of others as either largely capricious or largely determined. Those who took the latter view would be those with the metagene gene, and they would of course be better adapted and more successful, because awareness of living in a deterministic world allows one to better determine cause-and-effect relationships, and that is what leads to enhanced survival and the propagation of one's genes, including the metagene gene.

Okay, I'm being rather facetious. I do think evolutionary psychology has much value to add to the social sciences. But the glut of books by authors who seem themselves to believe there is a metagene gene is, I fear, doing more harm than good to the public understanding of how science and nature really work.

Fortunately, in most cases Ridley does an admirable job of clarifying the enormous complexities involved in gene-environment interactions, demonstrating in numerous cases that it is next to impossible to say that any complex human trait (such as intelligence or athletic ability) is, say, 60 percent genetically determined and 40 percent environmentally shaped.

For example, in "Chromosome 11: Personality" Ridley discusses the gene D4DR, which is located on the short arm of the 11th chromosome and codes for dopamine, a neurotransmitter that stimulates the organism to be active—or not, if a shortage exists: A complete lack of dopamine, for example, causes humans (or rats) to become catatonic, and high levels of it make them frenetic. Ridley here summarizes the fascinating work of Dean Hamer, who in his quest to find genes for smoking and homosexuality discovered the gene (or, more precisely, the gene complex) for the novelty-seeking personality. It turns out that the D4DR gene sequence is repeated on chromosome 11; most of us have 4 to 7 copies, but some have only 2 or 3 and others have 8 to 11. Those with more copies of D4DR have a lower responsiveness to dopamine in certain parts of the brain. Hamer theorized that this might mean that they would need to engage in more novelty-seeking behavior to get the same "dopamine 'buzz'" that people with fewer copies of the gene would get from simple things. He took 124 people who scored high on a survey measuring their desire to seek novelty and thrills and found that people who liked to jump off buildings and out of planes had fewer copies of D4DR than those who preferred knitting and watching grass grow.

When Hamer's research was picked up in the media, headlines declared that scientists had discovered the novelty-seeking gene, implying that perhaps all of our personality traits are so genetically coded. Fortunately, Ridley makes it clear that Hamer is claiming to explain no more than 4 percent of novelty-seeking behavior by D4DR sequences. That's nothing, as Ridley concludes:

This is the reality of genes for behaviour. Do you see now how unthreatening it is to talk of genetic influences over behaviour? How ridiculous to get carried away by one "personality gene" among 500? . . . Do you see now how futile it would be to practise eugenic selection for certain genetic personalities, even if somebody had the power to do so? You would have to check each of 500 genes one by one, deciding in each case to reject those with the "wrong" gene. At the end you would be left with nobody, not even if you started with a million candidates. We are all of us mutants. The best defence against designer babies is to find more genes and swamp people in too much knowledge.

Well said. But is this the general conclusion about genes that readers will come away with in this book? I hope so, but I fear not.

One quibble I had with Genome involves the final chapter, "Chromosome 22: Free Will." Granted, one cannot cover in one book the fine nuances of all positions in every debate in this vast field, but here Ridley leans far too heavily on the work of psychologist Judith Rich Harris, whose book The Nurture Assumption generated much heat (and, thankfully, some light) with its attack on psychology's long love affair with nurture arguments. Ridley writes: "Rich Harris has systematically demolished the dogma that has lain, unchallenged, beneath twentieth-century social science: the assumption that parents shape the personality and culture of their children." It turns out, Harris argues, that parents don't count for much at all in the development of adult personality. What does count? Genetics, of course, and peer groups. Families just don't matter.

Baloney. Harris is not without her critics, and readers, if they are to understand the nuances of the complex development of personality, deserve at least a paragraph or two about competing models. Research by Frank Sulloway, for example (summarized in his book Born to Rebel), shows that siblings and family dynamics are highly influential in the development of personality, which, in turn, shapes the interactions with siblings and parents in a chaotic and complex feedback loop. Given that I have not mastered the literature for all 23 of Ridley's chapter subjects, this example leaves me wondering what else he might have left out.

That critique aside, however, Ridley's numerous caveats throughout the book warning readers not to fall into the trap of oversimplifying a complex interaction of biology and environment will, I hope, help us override the tendency to divide nature into binary choices like nature and nurture—even if some metagene gene pushes us to do so.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.