The Man Who Found Time, Galileo's Finger and more...

By Robert Root-Bernstein

Short takes on four books and the Ig Nobel Prizes

Short takes on four books and the Ig Nobel Prizes

DOI: 10.1511/2003.38.0

In 18th-century Scotland, gentleman farmer James Hutton studied his land and came to a striking conclusion: The formations he saw could not have been shaped by one cataclysmic flood 6,000 years ago, as the Church taught. Moreover, the mundane forces of volcanoes, earthquakes, wind and rain could have sufficed to produce the entire landscape. The missing ingredient was "immense time."

This insight laid the foundations of modern geology and provided a necessary backdrop for the theory of evolution. In The Man Who Found Time (Perseus, $26), Jack Repcheck argues that Hutton deserves a pedestal next to Copernicus, Galileo and Darwin for helping to separate science from theology. In 200 pages, his sprightly book touches on biblical chronology, Edinburgh basalt, Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Scottish Enlightenment. It paints a portrait of a gifted if enigmatic man who insisted on believing his eyes.

A warning to aspiring revolutionaries: Hutton rubbed elbows with David Hume, Adam Smith and James Watt, but his 1795 book, The Theory of the Earth, was so long, obscure and poorly written that it sank without a splash. It fell to Charles Lyell to rescue and promote Hutton’s ideas. Moral: Heed your editor.—G.R.

In Galileo's Finger (Oxford, $30), Peter Atkins describes "The Ten Great Ideas of Science": evolution, DNA, atoms, energy, entropy, quanta, symmetry, cosmology, space-time and arithmetic. He chose these contributions to human understanding because they are concept-driven rather than tool- or applications-driven, he says, but he does not explain why ideas should be more valuable than inventions or why he chose these particular ideas. His discourse is that of a professor teaching a survey course to undergraduate nonscience majors. He's entertaining, offering lots of anecdotes (many, unfortunately, irrelevant) to keep the reader from bogging down in the ideas themselves. But in the end, despite having been told a great deal, one feels unenlightened.

Part of the problem is that Atkins doesn't make connections between ideas: Each symbol, metaphor and chapter stands alone. The movement of the chapters is ostensibly from concrete to abstract; unfortunately, this means that mastering one chapter provides the reader with nothing to build on for the next. Another problem is a lack of plot and motivation. Atkins would have been wise to follow the example of writers who put us intellectually in the place of the great discoverers, in effect allowing us to experience their surprising illuminations.

Perhaps Galileo's Finger will hold some appeal for scientists who have specialized too early and want to brush up on some of the main ideas outside their own field. But other books might do better for those who want a good survey of key ideas in modern science or mathematics: The Microverse, edited by Byron Preiss and William R. Alschuler; William Dunham's Journey Through Genius; Alan Lightman's Great Ideas in Physics; Isaac Asimov's Great Ideas of Science; Jacob Bronowski's Science and Human Values; Martin Goldstein's How We Know; and The Ring of Truth, by Philip and Phylis Morrison.—R.R.-B.

Corine Lacrampe's Sleep and Rest in Animals (Firefly, $24.95) is a Noah's Ark of snoozing critters. The large-format volume with 120 colorful photographs explores dormancy in everything from beetles to bears, raising as many intriguing questions as it answers.

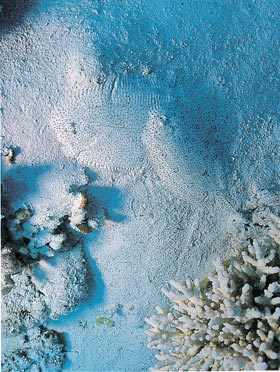

From Sleep and Rest in Animals.

Lacrampe's subjects reveal an astonishing variety of strategies for getting some safe shut-eye. Swifts sleep while flying, tuna while swimming. Flatfish (above) blend into the seabed sand when they rest, and their two eyes (both on the top side) go into "unseeing" mode. A surprising number of species, including mallards and some lizards, can put one brain hemisphere to sleep at a time, while the other stays alert to keep an eye on predators. Most mammals cycle through a stage of REM (rapid eye movement) sleep several times in a sleep period. Dolphins and other marine mammals, however, do not seem to need REM sleep at all.

The text goes beyond familiar sleep and rest to visit the strange fringes of hibernation, estivation and diapause, where we meet wood frogs who freeze solid without injury, snails who reduce their breathing by 99 percent during dry summers, and garter snakes who spend the cold months in dens of up to 10,000. Lacrampe competently summarizes what's known about sleep in animals, but much is still mysterious. Since behavior leaves no fossil record, it's not clear how sleep evolved; we still don't know what purpose it serves, or even whether all animals need it. Let's hope that future research will open our eyes.—G.R.

Every year on a Harvard University stage, Nobel Prize–winning scientists dodge paper airplanes and hand out the Ig Nobel Prizes, which honor "achievements that cannot or should not be reproduced." One lucky audience member wins a date with a Nobel laureate. And a young girl ("Miss Sweetie Poo") interrupts any speaker who goes on too long by making the repeated request, "Please stop. I’m bored."

The Ig Nobel (now in its 13th 1st Annual Year) has always been—and will always be—about real science. The Ig committee scours the globe for scientific endeavors that make one laugh—and think. An English physicist was toasted for determining that buttered bread tends to hit the floor buttery side down. Two Indian scientists were picked for their questionnaire about teenage nose picking. And executives and accountants at U.S. corporations such as Enron were lauded for using imaginary numbers in accounting practices. In The Ig Nobel Prizes (Dutton, $18.95), Marc Abrahams, founder of the awards and editor of the Annals of Improbable Research, describes many of the impressive studies that have received the honor. The book captures the spirit and history of the award for slightly less than the cost of a ceremony ticket and effectively reminds aspiring researchers that it’s always an honor just to be nominated.

More information about the Ig Nobel and the Annals of Improbable Research is available at www.improbable.com.—F.D.

Nanoviewers: Frank Diller, Robert Root-Bernstein, Greg Ross

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.