This Article From Issue

March-April 2025

Volume 113, Number 2

Page 122

OUT OF YOUR MIND: The Biggest Mysteries of the Human Brain. Jorge Cham and Dwayne Godwin. 368 pp. Pantheon, 2025. $28.00.

The mind is what the brain does. This truism, which I often tell my patients and students, is especially apt while reading Out of Your Mind: The Biggest Mysteries of the Human Brain by Jorge Cham and Dwayne Godwin. Although the authors spend a fair amount of time discussing the nature of the neurons and nodes that make up our brain (“a mere three pounds of gelatinous goop”), it soon becomes clear that this enigmatic organ still remains rather elusive to scientific inquiry. Thankfully, Cham and Godwin include abundant stories of brains doing things—surviving damage, responding to psychological experiments, and operating in ways both like and unlike the brains of other species—to help the reader understand the essence of what it is to be human, in all of our glory and ignominy. Oh, and there are cartoons!

In their book, Cham and Godwin attempt to “explain the most complex object in the known universe (the brain) using some of the simplest storytelling tools ever created (comics and cartoons).” This daunting undertaking necessitates making some choices. The book is not a textbook, and they are not comprehensive in their approach; rather, they approach the subject with a “curious mind,” aiming to spark wonder in the reader through some classic tales of the brain and mind, from both history and science, with an eye for visual storytelling. Similarly, they address some of the big questions of human existence, such as what love, hate, and free will are, and where we go when we die. These questions all lead back to the brain, which gives rise to the mind, which gives rise to you. And who are you? “The combination of your hopes and dreams and thoughts and memories and best and worst qualities,” they write.

Jorge Cham and Dwayne Godwin

Cham and Godwin cover these fundamental questions, as well as reviewing scientific developments and sharing tragic human stories of injured brains, starting with the Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus (an Egyptian document dating back some 3,700 years ago), which noted that certain head injuries resulted in behavioral symptoms, and gave the first description of the thing we call a brain.

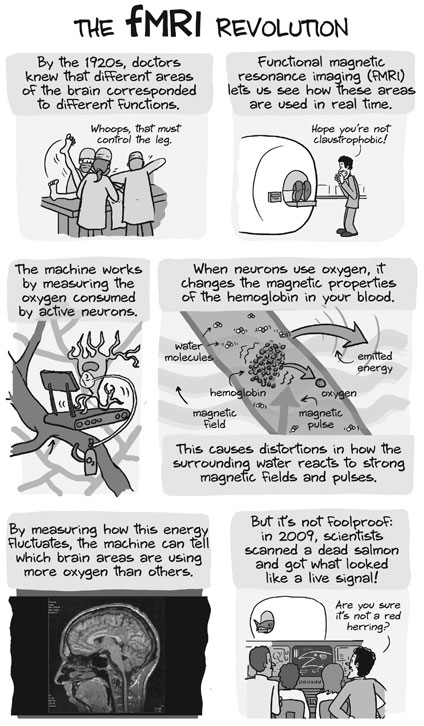

The variety of topics covered provides the reader with a broad overview of the fields of neuropsychology, neuroscience, psychology, and genetics without getting mired in the minutiae that would soon make one’s eyes glaze over. They favor the forest and sacrifice many trees, often using entertaining cartoons to cover complex topics. In this way, they explore the fascinating story of Phineas Gage, the railroad worker whose brain was pierced by an iron rod, changing his personality forever; how Alzheimer’s disease robs humans of their memories; even causes of and treatments for depression. Their visual approach provides details where necessary, but also breaks up what could otherwise often be very dense prose and complicated jargon, especially when explaining tools like functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Experts in various fields may be frustrated by the often cursory treatment of their disciplines or research areas, but the lay reader is well served by the deft and compassionate handling of complex topics, leaving room for further exploration, should one become inspired.

The chapter exploring the nature of consciousness was especially well done. Consciousness is a topic about which there is much speculation and arguing among scientists and philosophers. Many books have been written about consciousness, and there are several competing theories within the neurosciences regarding its origin and neural underpinnings. Cham and Godwin take the approach used consistently throughout the book: They teach by example. First, they discuss the concept of blindsight, or patients who are functionally blind but who can react to visual stimuli, such as balls thrown at them, which highlights the difference between seeing and perceiving. They also discuss examples of “split-brain” patients who underwent severing of the corpus callosum, the part of the brain that connects the right and left hemispheres, to help treat their seizure disorders. Finally, they discuss the interesting case of the Hogan twins, who are conjoined at the head and share parts of their brain structure and function. These twins report being able to see things that the other twin is shown, can control some movements of the other twin’s limbs, and can even hear the other twin’s thoughts. They appear to share aspects of a consciousness, despite having unique personalities and identities.

Cham and Godwin take the approach used consistently throughout the book: They teach by example.

Cham and Godwin hone in on one of the main theories of consciousness—the global workspace theory (GWT)—which proposes that multiple brain regions interact to build a “global workspace,” like a movie screen, on which our experiences play out. Finally, they provide a nice concluding summary to this enormously complex topic: “Ultimately, consciousness is the story we tell ourselves about ourselves. It’s the sense we use to sort out and interpret our internal, sometimes chaotic brain.”

Although the authors’ broad, visual approach largely works, it does come at a cost. For example, when describing various brain regions, the authors focus a lot of attention on the amygdala, insula, and so-called “reward systems of the brain” (that is, the ventral tegmental area), perhaps leading readers to wonder if these are the only regions that contribute to our higher thoughts and emotions, when in reality it takes most of our brain to carry out any complex human endeavor. Related to this is the focus on the so-called “fMRI revolution” which was actually an MRI revolution, with massive increases in studies using both functional and structural methods to correlate behavioral measures to brain function and structure (such as the size and thickness of various regions of the brain, and the integrity of connections between these regions). Structural measures are studiously ignored in the book, as are the vast array of electroencephalography (EEG) techniques, which measure brain electrical activity, and positron emission tomography (PET) studies, which measure energy use in various regions. Thus it’s an incomplete explanation, especially given how structural lesions of the brain have enabled neuroscientists to come to a better understanding of language, memory, personality, and diseases of the brain.

Cham and Godwin make it clear that it takes the contributions of philosophers, psychologists, neurologists, neuroscientists—and even cartoonists!—to scratch the surface of this complex organ that makes us human. They have walked a very fine line between being overly technical and pedantic, and being overly glib and superficial, presenting extremely complex studies and topics in an interesting and accessible manner without sacrificing accuracy or scientific credibility.

The idea that the “three pounds of gelatinous goop” giving rise to all of our hopes, dreams, thoughts, and fears—all that makes us human—can be captured so clearly and engagingly in words and cartoons, will ensure that Out of Your Mind is widely read by both laypeople and interested experts in neurology-adjacent fields. Cham and Godwin have succeeded in impressing at least one neuropsychologist while also wonderfully illustrating that there is so much still to learn about the brain. As they remind the reader, “Many of the answers in this book are incomplete, evidence that there are still great mysteries at every corner of the human psyche. . . . The mind remains a great frontier, and we need thinkers and artists to join us in exploring the perplexing cosmos within our heads.”

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.