This Article From Issue

July-August 1999

Volume 87, Number 4

DOI: 10.1511/1999.30.0

Deep Time: How Humanity Communicates Across Millennia. Gregory Benford. 192 pp. Bard Books, 1999. $20.

Astronomers, geologists and evolutionary biologists are accustomed to bantering about billions of years, but in most people's lives a decade constitutes "long-term" planning. Physicist/science-fiction writer Gregory Benford expands our horizons in the temporal dimension as he discusses attempts we humans have made, or should now make, to send messages across "deep time," meaning time scales of at least centuries and often millennia or far more. This short, fascinating book is for readers who enjoy thinking about the motivations and techniques of both those persons who sent messages from the past (such as the cave paintings of Lescaux, the Pyramids of Egypt and the monoliths of Stonehenge) and those who are sending messages to the future, such as the plaques and recordings attached to the 1970s Pioneer and Voyager spacecraft.

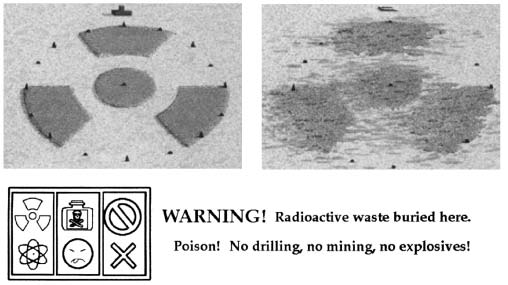

From Deep Time.

Benford analyzes and describes four projects or proposals in which he has played an important role. The first involved the issue of how best to mark a nuclear-waste disposal site buried in the salt of southern New Mexico. Environmental regulations led to a charge to two panels, of which this reviewer was also a member, to concoct schemes that for the next 10,000 years (!) would effectively warn and deter any future societies from being exposed to radiation. It's hard to know if we succeeded, but Benford gives an excellent overview of what the design process was like, and the kinds of issues tackled by sociologists, archaeologists, geologists, artists, landscape architects, materials experts and astronomers. It was surely one of the headiest official government panels ever convened.

His second project involved the design of a diamond medallion message to fly on the Cassini mission to Saturn, launched in 1997 (and arriving in 2004). With artist Jon Lomberg, Benford cleverly constructed a message that would both survive and have a decent chance of being understood, if anyone should ever come upon it millions of years in the future. For instance, the time of the message's creation was indicated on scales ranging from 105 years to 1,010 years by including images of the current status of slowly changing astronomical phenomena such as Saturn's rings, the moving stars in the constellation Ursa Majoris, the rotating galaxy Messier 74 and the gravitational collection of galaxies known as Abell 2151. But on earthbound, political timescales, this story did not have a happy ending, for after two years of work (and only nine months before launch) controversy at NASA over who did what in the end led to a decision not to fly the medallion at all.

Benford's third and fourth "messages" through deep time are proposals for what we should do now for the benefit of our distant descendants. In 1992 he published a simple idea that created quite a fuss: Let's pick a random sample of extant species, say one million, and freeze their DNA (or perhaps even entire organisms) for the benefit of posterity. Thus despite the alarming rate at which species are now going extinct ("there is no more firm message than extinction"), at least this amount of knowledge would be passed on. Benford poignantly likens our situation to a person running through the hallways of the great ancient library of Alexandria as it burns to the ground. Only a fraction of the manuscripts can be saved, and he argues that the best strategy for preserving knowledge in such a hurried, dire circumstance would be a random sample.

Benford's final deep-time message, informed by his science-fiction proclivities, is to enthusiastically embrace geo-engineering to solve environmental problems such as the present global warming due to the burning of fossil fuels. He argues that Homo sapiens have been modifying the ecosphere in fundamental ways ever since their appearance; what's different now is that we can do so advertently. Engineering solutions today would mean a profound cultural shift, in that we would be consciously planning ahead for centuries and millennia. If we began to technically manage the planet, it would be "our era's most lasting deep time monument," as we adopt the mantle of planetary stewardship.

You may not agree with all of Benford's ideas, but there's no doubt that a book like Deep Time will invigorate and inform your thinking. We've received many messages from the distant past, but what are we sending, either purposely or inadvertently, to the future?

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.