This Article From Issue

November-December 2008

Volume 96, Number 6

Page 514

DOI: 10.1511/2008.75.514

MEASURING THE NEW WORLD: Enlightenment Science and South America. By Neil Safier. xviii + 387 pp. University of Chicago Press, 2008. $45.

In 1735, a team of French and Spanish scientists traveled to South America as members of the Geodesical Expedition to the Equator. Their goal was to help determine the true shape of the Earth: Was it flattened at the poles and bulging around the equator (as the work of Isaac Newton and Christiaan Huygens suggested), or was the bulge at the poles rather than at the equator (as the French Cartesianists would have it)? To settle this matter, the Paris Académie des Sciences commissioned two metrological expeditions: one to Lapland, near the North Pole, and the other to Quito, near the equator. Measuring the length of a meridian arc of one degree at each of these two sites and comparing the results would resolve the issue. As it turned out, Newton was correct.

The equatorial expedition entailed unprecedented international cooperation, because Spain had long forbidden foreigners to travel in its American dominions. It also provided a wide European public with rare information about equatorial South America, the fabled land of the Incas, the Amazons and El Dorado. For the next nine years, the team traveled widely, conducting geodesical measurements. Its members also gathered information about a territory that Europeans still knew little about 200 years after the Spanish conquest of the Inca empire.

Measuring the New World, by Neil Safier,is a deft, thoughtful examination of what happened to European Enlightenment science in an American setting, and of how South America was depicted in Europe as a result of this exploration. What makes Safier's book stand out from other works on scientific travel is the way in which he masterfully expands the range of sites, practices and participants. This is not the story of an expedition, but rather a study of the stories the expedition yielded through words and images, in multiple languages and in many different places.

Safier's original insight, which he richly mines, is that traveling was but the first step of a long and involved process that entailed crafting and publishing textual and pictorial accounts, handling material collections and responding to accounts both in manuscript and in print. The creation of knowledge about South America took place not only in the New World but also in European print shops, scientific societies, gardens and museums, and it involved a vast cast of characters of various nationalities, many of whom had not taken part in the voyage themselves.

The expedition yielded a wide range of materials, some addressing the trip itself and some focusing on the region more broadly. Safier devotes one chapter each to four intriguing sources,all of them manufactured in Paris: the best-known travel narrative to emerge from the expedition; a map of the province of Quito; a historical account of the Inca empire; and the depiction of the Amazonian region in the Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert. All of these works showcase two central epistemological methods at work at the time: accumulation and abridgement.

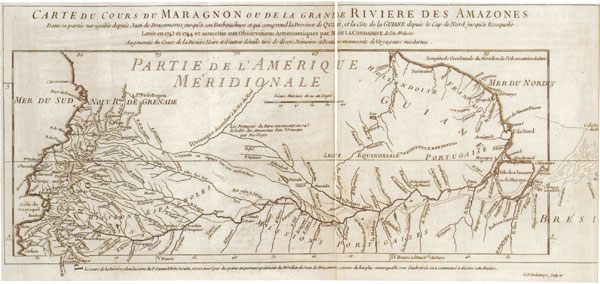

From Measuring the New World.

Chapter two explores the first of these sources, the best-known account of the expedition—the Rélation abrégée d'un voyage fait dans l'intérieur de l'Amérique méridionale, which was published in Paris in 1745. Its author, Charles-Marie de La Condamine, returned from the voyage with a collection of maps, manuscripts, letters and stories that he had gathered from local informants. He drew on all of them for the Rélation abrégée and also made liberal use of previous publications—the expedition's traveling library had occupied 21 trunks of books, from which La Condamine culled anecdotes and at times excerpted entire passages, word for word. Adhering to the notions of scientific authorship current at the time, La Condamine portrayed the material in the Rélation abrégée as being the result of his own personal experience and eyewitness observations; he underplayed the assistance he received from local residents and the contributions of previous explorers. Compiling, editing and narration proved as important to La Condamine's text as the voyage itself.

Something similar happened with cartographic material. In one of the book's most satisfying chapters, Safier takes us behind the scenes in an 18th-century cartographic atelier, where we can trace the creation of the Carta de la Provincia de Quito y de sus adjacentes (1750). We follow the map's manufacture from a draft that incorporates a plurality of authorial and editorial voices, through the negotiation of revisions, to an image that is printed in various versions for different audiences. In Safier's fascinating account of the ways in which geographical, religious, historical, ethnographic and administrative information is distilled into cartographic statements, the map emerges "not as a fixed and burnished image of geographical space but rather as the product of social and material itineraries."

Such itineraries often transformed editors into authors, reshaping materials to the extent of rendering them unrecognizable. That was the case with the 1744 Paris edition of Histoire des Incas, rois du Pérou. The original book, by "El Inca" Garcilaso de la Vega, the son of a Spanish conquistador and an Incan princess, was published in 1609. To produce the new French version, an unnamed editor at the Parisian Jardin du Roi reshuffled the original text as he saw fit, compressing, rearranging or deleting material and adding new footnotes and bracketed passages. Accusing the original text of "disorder" and "confusion," the editor thoroughly transformed it. The revised book showed less interest in Inca history than in contemporary French concerns about botanical and agricultural organization and productivity—a scientific and political issue in which the Jardin du Roi was highly involved.

Likewise, a final chapter examines the abridgement and redistribution of the expedition's materials for inclusion in the Encyclopédie. La Condamine's appropriation of the work of local informants and previous authors to produce his own narrative suffered a comparable fate at the hands of the encyclopedists, who distilled personal anecdotes and experiences that were embedded in a narrative into universal truths splintered among 85 short articles. Safier draws a parallel between the mapping of equatorial South America and the mapping of human knowledge in the Encyclopédie, characterizing both as Enlightenment projects that aimed "to parse knowledge into its component parts and reconstruct the pieces in an abridged form suitable for easy digestion by a broad, learned public."

Measuring the New World analyzes not only these varied accounts of South America but also contemporary reactions to them. "The journey of a philosophical traveler," Safier reminds us, "did not end with the publication of a printed text. Instead, after publishing a travel account, the author's attention necessarily turned to the ever-precarious itinerary of his literary reputation." And precarious it proved indeed.

Readers in Europe and the Americas criticized La Condamine's Rélation abrégée, questioning his epistemological authority—given his limited knowledge of indigenous languages and the length of his stay in South America—and suggesting that he must have relied on ignorant informants. La Condamine's appropriative authorial practices found their counterpart in readers' appropriative uses of his text, portions of which they selectively accepted or rejected based on their own affiliations and the uses to which they could put this information.

Another account of the expedition, published in Madrid in 1748 by Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, the two Spanish naval officers who participated in the expedition, drew the ire of an anonymous critic, who wrote a heated denunciation of the account's pejorative treatment of the indigenous population of Quito. This critique in turn elicited a response from a second reader, who defended the travelers' vision. The debate between these two readers about ethnographic description, like the critiques of La Condamine's narrative, highlights the existence of differing views about the proper ways to observe, understand and represent American populations.

Measuring the New World offers a captivating account of the "challenges of extracting meaning from an entangled corpus of natural knowledge," skillfully reconstituting the material practices and social relationships of scientific exploration in a transatlantic Enlightenment.

Daniela Bleichmar is assistant professor in the departments of Art History and Spanish and Portuguese at the University of Southern California. She is the author of multiple articles on the history of science, visual culture and travel in colonial Latin America and is coeditor, with Paula De Vos, Kristin Huffine and Kevin Sheehan, of Science in the Spanish and Portuguese Empires, 1500-1800 (forthcoming from Stanford University Press in December 2008).

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.