This Article From Issue

January-February 1999

Volume 87, Number 1

DOI: 10.1511/1999.16.0

Salt, Diet and Health: Neptune's Poisoned Chalice. Graham A. MacGregor and Hugh E. de Wardener. 233 pp. Cambridge University Press, 1998. $64.95.

We are told that a Stone Age diet was healthier than contemporary cuisine. It reminds me of the story of the general reviewing the troops.

"How's the chow?" he asks a private.

"It's fine, sir. What there is of it."

"Do you mean you're not getting enough?"

"Oh, no, sir. There's plenty, such as it is."

The theory is that human beings evolved in an environment of scarcity. They ate plenty of wild fruits and vegetables. Occasionally they would gorge on the meat and fat of a hunted animal. Those who could retain nutrients well had a survival advantage. Today food is plentiful and readily available, so our evolutionary adaptations have become a burden. In an engineered atmosphere of plenty, our primeval bodies are succumbing to the scourge of abundance.

From Salt, Diet and Health.

Graham MacGregor and Hugh de Wardener have applied this argument to salt. Dietary sodium chloride, they say, increased tenfold when humans began using it to preserve food. Over 5 to 10 millennia, the rising ingestion of salt led to an addiction, the cost of which is high blood pressure that leads to stroke and heart disease.

The book is a series of reviews, each of which is nicely summarized and accompanied by a reference list. The first third looks at the mythology, history and geography of salt. In addition to being interesting, this information is necessary to explain how firmly embedded the tradition of a high salt intake has become in our lives. Most of the rest of the book presents the evidence of salt's effect on health, covering blood pressure and its relation to salt intake as seen in clinical and animal studies and in comparisons of populations, the hypothetical role of the kidney in determining susceptibility to hypertension, diseases related to hypertension, hypertension management and the association of salt with diseases that are not secondary to hypertension. Ultimately the book paints the salt and food industries as conspirators in a plot to prevent the public from recognizing the threat to health, a conspiracy that they liken to the tobacco industry's efforts to obscure the relationship between their product and morbidity. An appendix offers advice on practical ways to reduce salt in the diet. This comprehensive treatment of the topic is the most outstanding feature of this work.

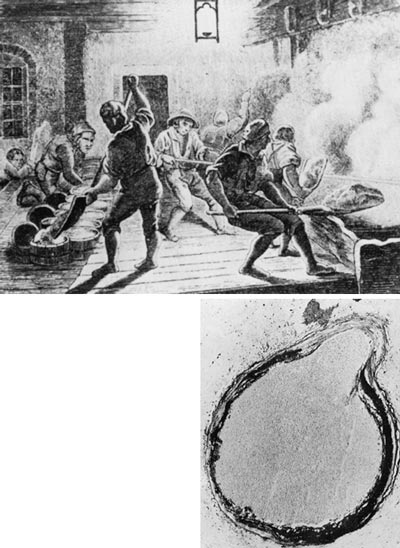

The text is generously illustrated with graphs, drawings and photographs. I particularly liked some of the historical illustrations, such as Stephen Hale's observation of the height to which blood rose in a cannula inserted into an artery. This is a demonstration that we still use to illustrate central venous pressure to residents and cardiology technicians.

We should not be too quick to accept the authors' hypothesis that an unidentified genetic defect in the kidney is the only cause of hypertension. As geneticists investigate the problem, the picture becomes more complex. Recently published research links a mutation in the angiotensinogen gene to hypertension. Angiotensinogen is synthesized in the liver, not in the kidney as inferred by the book's discussion of the renin-angiotensin system.

Essential hypertension, which affects 90 percent of high blood pressure patients, is by definition of unknown origin. Even a cursory search of the literature indicates that it involves multiple genetic and environmental factors. Although not everyone would agree that salt is the primary cause of hypertension, most would agree that reducing its intake should be beneficial. This book is worth reading to see the authors' evidence implicating salt as the prime suspect and to learn the role of salt in life and legend.—John A. Ward, Clinical Investigation, Brooke Army Medical Center

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.