This Article From Issue

March-April 2021

Volume 109, Number 2

Page 66

The first step to finding an answer is to realize you need to ask the question, and that can be tricky. As we move along within our frameworks and routines, familiarity might prevent us from seeing outside our bubbles. It’s often the case that if you break out, take a step back, or otherwise find a different angle, inspiration will strike. We all see the world through our personal lenses, to borrow a phrase common to psychologists and ethicists, who use the idea to remind us that people interpret the world differently. Indeed, Destinée-Charisse Royal, a senior staff editor at the New York Times, frequently recommends “loaning your lenses” as an effective tool in conflict resolution. But learning to switch out your standard lenses, and maybe see the world through someone else’s, can be a fruitful skill to develop for many reasons.

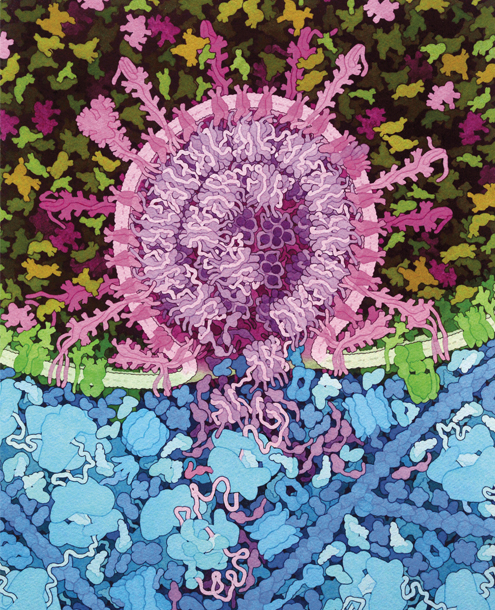

Courtesy of RCSB Protein Data Bank

Scientists know that artwork has explanatory power when used to illustrate discoveries, but some of them may not realize that art is valuable as a tool for making breakthroughs. David S. Goodsell would like to make that clear, and he describes in this issue’s Arts Lab column (Painting a Portrait of SARS-CoV-2) how he uses his artwork to get new perspectives on science that interests him. Goodsell is a biologist, and he’s also a renowned illustrator of the internal workings of cells and microorganisms. Goodsell emphasizes that when he’s making a new art piece—one featuring SARS-CoV-2, for instance—he needs to ask a lot of questions about the structure and the function of the cells he is attempting to depict in detail. His searches for all the “bits of information,” he says, often lead him to ask more questions and do more literature research across fields, to find the molecular-level specificity he requires. And he hopes that his work will induce experts in those fields to ask more questions as well. In his SARS-CoV-2 Fusion painting (above), he notes that there’s still a lack of information about how the structure of a spike protein changes while it’s in the process of fusing with a cell membrane. He would be pleased if scientists in these fields are inspired to confirm or disprove his educated guesses.

Marc Hellerstein, in Remembrance of Germs Past, also discusses how a broad range of experience, and some serendipity, moved along his research regarding cell proliferation, which was a first step in tracking the life spans of T-cells. Hellerstein’s background working with glucose metabolism allowed him to see new ways of getting safe tracers into DNA at the time it is synthesized, and his connections with vaccine researchers let him work on the ways T-cells could mount a response to invaders not encountered for decades.

Most of our analogies for gaining a new perspective are visual—a different point of view, a change of scenery. But as Adam Zeman points out in Blind Mind’s Eye, not every brain can visualize. Some people simply can’t create an image in their mind’s eye based on a description. Zeman points out that people with this condition, called aphantasia, lead rich mental lives nonetheless, even though their sense of perception is perhaps more abstract than experiential. It’s a good reminder that there are lots of different ways to think about things.

Has using a different mental lens (visual or not) ever resulted in a breakthrough for you? Let us know about it. You’re always welcome to reach out to us via our website form or on social media. —Fenella Saunders (@FenellaSaunders)

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.