Subtle as a Flying Hammer

By David Samuel Shiffman

Does the hammerhead shark’s funky head shape give it a lift underwater?

Does the hammerhead shark’s funky head shape give it a lift underwater?

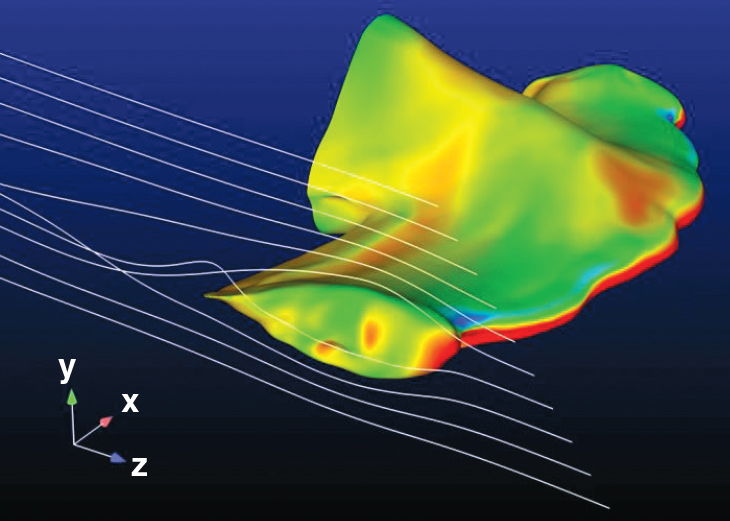

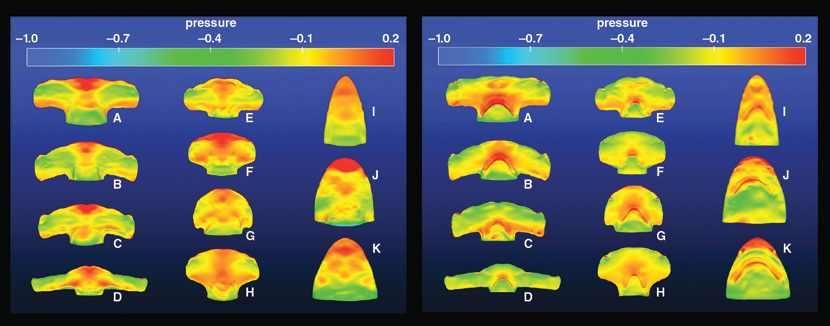

The cartoonish, elongated skull of the hammerhead shark looks so much like a wing—the structure’s technical name, cephalofoil, means “head wing”—that many researchers and shark enthusiasts have wondered if it also acts like one, generating underwater lift or improving maneuverability. A study of the hydrodynamics of the cephalofoil, published in the journal Scientific Reports, has now provided an answer, and produced the eyecatching images below as a bonus.

Matthew Gaylord, a graduate student at the University of Mississippi, and his colleagues began the study by taking a bunch of severed shark heads obtained from a fishing tournament to a laser scanning laboratory at a nearby engineering facility. But this method rapidly required modification, because sharks, which have urea in their blood, smell extraordinarily bad when they’re dead, and the engineers at the facility weren’t happy about it. Eventually Gaylord and his colleagues settled on making their own plaster and silicone molds of these shark heads to scan instead. The team was able to make molds and take digital scans of eight species of hammerhead sharks; they then ran fluid-dynamics computer models on the scans to study how water flows around the hammerhead’s strangely shaped face.

Images courtesy of Matthew Gaylord and Glenn Parsons, from Scientific Reports 10:14495

The team found that the cephalofoil does seem to allow for increased maneuverability, which wasn’t surprising: “Based on what I’ve seen with hammerhead sharks moving underwater, they’re just so nimble; they can change direction much faster than other sharks,” said Glenn Parsons, a biologist at the University of Mississippi and a study coauthor. In earlier studies, the cephalofoil was shown to be useful in pinning prey to the ocean floor, and to help with sensory systems, so the head has several adaptive applications.

But does the cephalofoil provide lift? It doesn’t, as it turns out. The beautiful pressure diagrams at left and below show a negative result: If the cephalofoil were providing lift, the bottom of the head would be red (high pressure) and the top would be entirely green and blue (low pressure), but the red is only in front, not underneath. “We consider that a myth busted!” Gaylord said. –David Shiffman

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.