The Formation of Star Clusters

By Yuri Efremov, Bruce Elmegreen

Clouds in the summer sky provide clues about the organization of star populations

Clouds in the summer sky provide clues about the organization of star populations

DOI: 10.1511/1998.25.264

At the beginning of the universe, when the galaxies first appeared, there were no stars at all. The first stars began to form only after the hot, gaseous galaxies had time to cool. The densest of these early galaxies worked quickly, turning all of their gas into stars when the universe was still quite young.

Others, like our own Milky Way, puttered along at a relatively modest rate of star formation. Indeed, our Galaxy has a lot of gas left, and is still forming stars today at a rate of about 10 per year. These stars are forged in what might be called stellar nurseries: vast clouds of dust and gas where tens, hundreds or even thousands of stars are born.

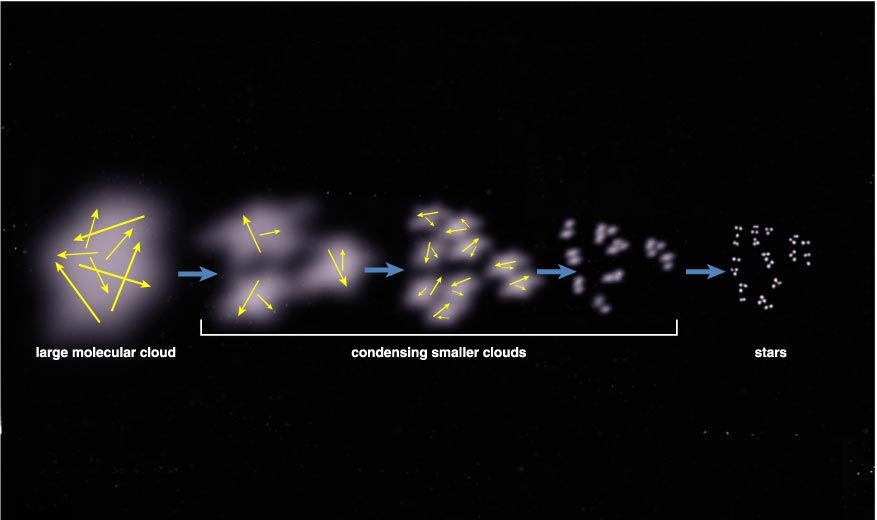

The nature of these gas clouds and precisely how they evolve to form the distribution of stars we see in the sky is one of the classic puzzles of astronomy. It has proved to be especially challenging because the formation of a star cluster is obscured by the same dust and gas that fuels the process. Moreover, the birth of a star like the sun takes place over the course of millions of years, many times longer than the age of our species. Such ephemeral beings as astronomers must deduce the mechanism of cluster-building from observations of present star groups in the Milky Way and neighboring galaxies.

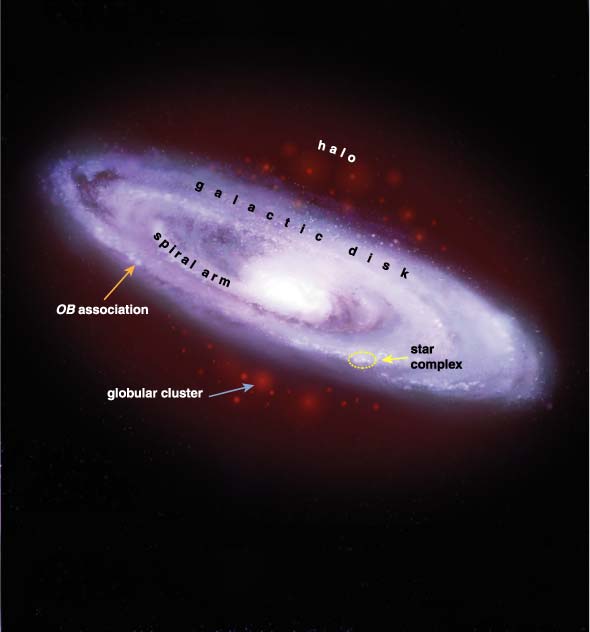

As it happens, the star clusters we see in the sky are not all alike. Clusters in one part of our Galaxy (the thin disk, which includes the spiral arms) appear to differ from those in another part (the Galactic halo, a vast spherical area that surrounds the disk). Some star groups are densely packed in small volumes of space, whereas others are distributed over large expanses. Stars in some groups are gravitationally bound to each other, whereas stars in other groups are drifting apart. Some star groups are ancient, dating to the time when the galaxies first formed, yet others appear to be caught in the act of forming.

Linda Huff

Because of this apparent diversity, astronomers have long assumed that the mechanisms involved in the formation of each type of cluster were unique. Certainly conditions do differ across the Galaxy, and there is reason to believe that the universe was a very different place when the galaxies first began to shine. But do these differences prohibit the existence of a common mechanism?

Our research suggests that all clusters, regardless of age and appearance, can be explained by the same basic mechanism: the structuring of star-forming gas into a hierarchical distribution of clouds by the action of turbulence and gravity. Here we describe some of the evidence for this process and address some of the previous objections raised against the idea of a universal mechanism.

Many star groups are visible with the naked eye or a modest telescope to anyone living under dark skies. The famous Pleiades cluster in the constellation Taurus and the double cluster (h and c Persei) in Perseus are obvious to even the most casual stargazer. Each of these open clusters consists of several hundred to a thousand stars that are gravitationally bound to each other in a volume of space no more than a few tens of light-years across. Their stars are typically born at about the same time (give or take a few million years) and may stay bound to each other for more than 100 million years. Located within the disk of the Galaxy, most of them are eventually disrupted by passing clouds of dense gas.

Other groups of stars in the Galaxy's disk, including many of the brightest stars in the constellation Orion, are more loosely distributed than the Pleiades cluster, with thousands of stars stretching across several hundred light-years. These giant stellar groups are not gravitationally bound, but can be recognized by the presence of bright, blue stars, known as O-type and B-type stars (according to their spectral properties). The stars in these so-called OB associations are recognized as belonging to a single group because they are concentrated in space and moving in the same general direction through the Galaxy. Since OB stars are massive, they burn their fuel very quickly, often within 10 million years of their birth. (At 5 billion years, our lower-mass sun is only halfway through its life span.) Such brief lives for OB associations make them convenient markers for the location of recent star formation.

Attempts to understand the distribution of open clusters and OB associations in the Galaxy led astronomers of the 1950s and '60s to turn their telescopes toward other galaxies in the hope that some would provide a better perspective. But identifying extragalactic OB associations proved to be challenging because individual stars in other galaxies were too faint to be characterized by their spectra at that time. An OB association in another galaxy could only be recognized by its relatively high stellar density.

The subjective methods of the astronomers produced a wide range of sizes for OB associations. In 1961 Paul Hodge and Peter Lucke of the University of Washington found that the average OB association in the Large Magellanic Cloud (a satellite galaxy of the Milky Way) was about 250 light-years across. But a decade earlier the Harvard astronomer Harlow Shapley found star groupings in the Milky Way's satellite that were 1,300 light-years across. Sidney van den Bergh, then at the David Dunlap Observatory in Toronto, found what he called "OB associations" that were 1,500 light-years across in the great galaxy in Andromeda (M31). At the time it was not clear whether these results were in conflict with each other or whether OB associations could actually have a wide range of sizes.

The reason for the diverging results became apparent in studies of OB associations in the 1970s and '80s. One of us (Efremov) and the Bulgarian astronomers Georgi Ivanov and Nikola Nikolov found small, compact groups inside nearly every large group of stars in the Andromeda galaxy. These small groups were also bluer and brighter, suggesting that they were younger than the large groups. The average size of the smaller groups was about 250 light-years, the same size as the OB associations in the Large Magellanic Cloud described by Hodge and Lucke. This is also about the size of the stellar associations in the Milky Way, including the Orion OB association.

How then could the large OB associations be explained? Since the small OB associations appeared to be parts of larger star groups in the Andromeda galaxy, the small Milky Way associations could be parts of larger groups here too. Evidence for this idea came from our work on Cepheid variable stars, massive stars that happen to be in a relatively late phase of stellar evolution as we observe them today. He found that Cepheid variables clump together in the Milky Way, much like OB stars, but on a larger scale, spanning 1,800 light-years or more. These large clumps, or star complexes, may be 50 million years old, about five times older than a typical OB association.

It turns out that the nearest star complex in the Milky Way corresponds to a great swath of stars surrounding us that was studied by the 19th-century American astronomer Benjamin Gould. This vast system, now called Gould's Belt, does indeed house several star-forming regions, including the Orion-, Perseus- and Scorpius-Centaurus OB associations. Furthermore, the Dutch astronomer Adriaan Blaauw recognized that there is also an older, dispersed association of stars, called Cas-Tau (after its location in the constellations Cassiopeia and Taurus). Star formation in the Cas-Tau association ended some 20 million years ago, so this grouping is now considered to be the first generation of star birth in Gould's Belt, whereas Orion and the other local OB associations belong to the second generation.

Efremov and his collaborators also determined that the large concentrations of OB stars found in the Andromeda galaxy by van den Bergh are clumps of Cepheids too, and are therefore much older than the smaller OB associations. These observations have been extended to other galaxies as well. The large, rich complexes of Cepheids in our Galaxy are the same size as giant "star clouds" detected along the spiral arms of several other galaxies. (Remarkably, the astronomer Frederic Seares suggested back in 1928 that these knots are similar to Gould's Belt.) It appears that about 90 percent of the OB associations and young clusters in the Milky Way, the Large Magellanic Cloud, the Andromeda galaxy and another nearby galaxy, M33, are all united into star complexes.

All of these observations imply that OB associations are merely the young cores of older and larger groupings of stars. They also suggest that there were probably other OB associations inside each Cepheid complex in the past, and that these older stars are now dispersed.

We now believe that star complexes are the fundamental scale for star formation in spiral galaxies and irregular galaxies, and that the construction of these complexes may extend up to the lengths of short spiral arms. Moreover, the hierarchical relation between OB associations and star complexes appears to continue in the opposite direction, toward smaller scales. Most OB associations contain clumps of smaller clusters (called subgroups by Blaauw), and these often contain even smaller collections of stars. (For example, the double cluster, h and c Persei, is part of an OB association discovered by William Bidelman of Case University in 1943.) These small collections are themselves made of multiple-star systems. All of these observations suggest that star formation is generally clumped into a hierarchy of structures, from small multiple systems to giant star complexes and beyond. OB associations are just one level in this hierarchy.

The hierarchical structure of star clusters helps to explain why astronomers had such difficulty defining star groups, since any such division is arbitrary. But it left an unsettling question: Why are stars arranged hierarchically when they form?

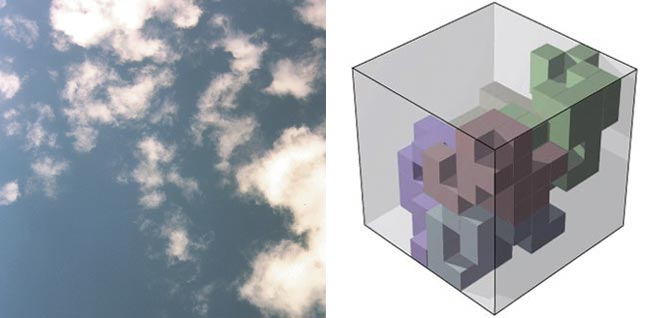

Over the past decade it has become apparent that much of the gas between stars is itself arranged in a hierarchical structure. This structure is evident across a wide range of gas-cloud sizes, from the smallest clumps that can be resolved with a telescope to giant clouds in the Galaxy's spiral arms. The large clumps of gas contain smaller clumps, most of these contain even smaller clumps, and it seems likely that this trend continues below the present limit of telescope resolution. This hierarchical structure is even present in clouds that are not forming stars, so it has little to do with the star- formation process itself. A clue to the cause of this structure comes from a closer examination of its properties.

As it happens, the hierarchical structure of interstellar gas clouds is approximately self-similar for a wide range of scales: The largest clouds are divided into smaller clumps in the same way as the smaller clumps are divided into even smaller clumps. In this respect, interstellar gas clouds are fractal, with a well-defined fractal dimension. The fractal dimension of a hierarchical structure is equal to the logarithm of the average number of subclumps inside each clump, divided by the logarithm of the size ratio of the large clump to the average small clump.

Consider a solid object such as a cube. It is three-dimensional, and its fractal dimension is also three. We can see this by dividing a cube into eight subcubes, with the side of each subcube half the length of the original cube. So there are two subcubes along each width, two along each height, and two along each depth, for 2 x 2 x 2 = 8 total subcubes. The logarithm of eight divided by the logarithm of two equals the fractal dimension of three. Or we could divide it into 3 x 3 x 3 subcubes (similar to a Rubik's cube), giving log 27/log 3 = 3, for the fractal dimension again.

If the partitioned cube is not completely filled, but only five of the eight subcubes are filled and the rest empty, then the fractal dimension is log 5/log 3, which is about 2.3. Now we can make a bigger hierarchy with this fractal dimension by subdividing each filled subcube into eight more and choosing another five of these for further subdivision, and so on down to arbitrarily small scales. The fractal dimension of this whole structure would still be 2.3.

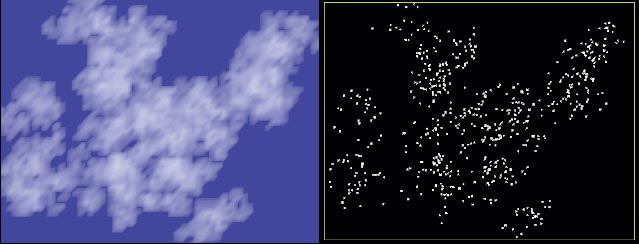

Many attempts have been made to assess the fractal dimension of interstellar gas clouds. A recent study by one of us (Elmegreen), with Edith Falgarone of Paris, used the relative number of clouds and clumps of various sizes to derive a dimension of 2.3. (The example above was not chosen arbitrarily!) This result might not be otherwise interesting to astronomers, except that it is remarkably similar to the fractal dimension of structures seen in the earth's atmosphere, such as the wispy and swirling plumes in jet trails and atmospheric clouds. Indeed, billowy white clouds in the summer sky look a lot like star-forming clouds.

On earth, the self-similar structures in smoke plumes and atmospheric clouds are the result of turbulence. Turbulent motions produce hierarchical structures because the large-scale parts of the motion produce the large-scale concentrations, and the small-scale parts of the motion produce the small-scale concentrations.

Many people think of turbulence as the random jittery motions that toss airplanes around in an unpredictable fashion. But there is also a regular and systematic element to turbulence: Nearby regions tend to move at about the same speed, whereas distant regions move more independently. Very simply, the greater the separation between two fluid elements, the greater the difference in their relative velocities.

Most earth-bound turbulence has a pattern of velocities that increases as the cube root of the separation. This pattern appears to be generally true for incompressible fluids, and for disturbances in air that are at such low pressures that the density remains fairly constant. The relation is a little steeper for astronomical turbulence, with velocity scaling approximately as the square root of the separation. The difference may be the result of larger pressure fluctuations for astronomical turbulence. These fluctuations tend to be so large in space that they actually compress the gas, forming density enhancements. These are presumably the same density enhancements that make newborn star clusters.

The important point is that the velocity structure in turbulent regions of space is scale-free: The same physical processes and the same velocity-separation relations occur over a wide range of absolute scales, from hundredths of a light-year to thousands of light-years. The large velocities on large scales compress the gas into large clumps, and the small velocities on small scales compress the gas into small clumps. If the velocity structure in space is scale-free, then the density structure that results from these motions should be scale-free as well.

We believe this is the reason for the hierarchical structure of gas clouds in space, and for the analogous structure of the birth places of stars. Star clusters of all sizes are formed by the conversion of gas into stars, following the compression of gas into hierarchically distributed clumps in a turbulent interstellar medium.

The link between the hierarchical structure of gas clouds and open clusters is evident in the distribution of their masses. Hierarchical gas clouds have an intrinsic mass distribution in which the number of clouds with masses in a fixed interval M is proportional to 1/M2. So there are 100 times as many clouds with masses between 9 and 10 solar masses as there are clouds with masses between 99 and 100 solar masses, which is a factor of 10 larger. This mass distribution turns out to be the same as the distribution of masses for open clusters, a value we were able to establish in a recent study of large and small clusters in the Large Magellanic Cloud.

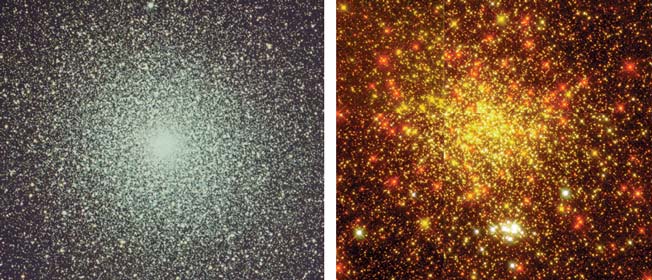

The hierarchical structure of gas clouds and star clusters is apparent in the disk of the Milky Way, but there is another type of star grouping—the globular clusters found in the Galaxy's halo—that appears to challenge some of our ideas about the formation of clusters. Globular clusters are very compact and massive compared to open clusters. They may contain 100,000 to 1,000,000 stars within a volume of space no more than 20 or 30 light-years across. Remarkably, the globular clusters in the Milky Way's halo appear to be as old as the Galaxy itself, perhaps 10 to 15 billion years. For many years astronomers believed that the conditions needed to produce a globular cluster were no longer possible in today's universe. There are a few hints, however, that this is not the case.

In the Large Magellanic Cloud there are compact clusters that look very much like globulars. In 1951 Shapley and Virginia McKibben-Nail at Harvard University found a dozen Cepheid variable stars in one of the largest of these (NGC 1866). When this discovery was made it was surprising because it implied that the cluster is relatively young. The young age was also consistent with the blue color of the clusters. Hodge later confirmed that most of the Magellanic "globulars" were indeed quite young. These results were so disturbing to astronomers' ideas about globular clusters that they coined a new term for these objects, blue populous clusters.

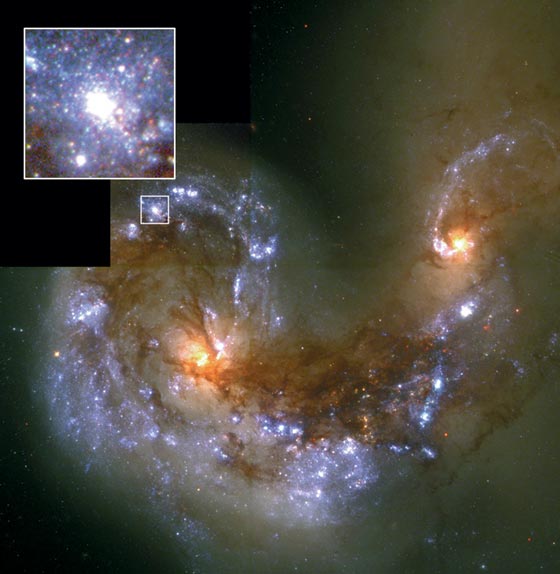

Similar clusters have since been found in the disks of other galaxies, mostly in regions of intense star formation. Recently Bradley Whitmore of the Space Telescope Science Institute and Francois Schwiezer of the Carnegie Institution used the Hubble Space Telescope to uncover more than 1,000 luminous blue knots in the disks of two interacting galaxies, NGC 4038 and NGC 4039. These knots are as bright and blue as halo globular clusters would have been when they formed 10 to 15 billion years ago, but they are caught in the act of forming today, with the oldest age only a few hundred million years!

Some astronomers have argued that blue clusters in merging galaxies are unbound associations that will not evolve into old globular clusters. Like all of the disk clusters (bound or unbound) in our Galaxy, the young globular clusters in colliding galaxies have a scale-free distribution of masses. In contrast, old halo globular clusters have a very different mass distribution, one that is not scale-free but is centered around a characteristic mass of about 100,000 suns. This has prompted van den Bergh to suggest that the young luminous clusters in NGC 4038/4039 are more like Galactic-disk clusters than halo globular clusters.

This argument is difficult to refute, but another explanation for the centered mass distribution of old globular clusters is possible. Several astronomers, including Vladimir Surdin of the Sternberg Institute in 1979, Tadashi Okazaki and Makoto Tosa of Tohoku University in 1995, and ourselves, have conjectured that the whole distribution was born scale-free, but the low-mass clusters have since been destroyed, leaving today's distribution of masses peaked at some intermediate value. This scenario is consistent with theoretical work suggesting that low-mass globular clusters can evaporate or get destroyed by collisions with the galactic disk in a time shorter than the age of the universe, but the high-mass globulars can persist.

The high mass of the young globulars in interacting galaxies raises another question too, because all high-mass clusters in the disks of normal galaxies are unbound. Why should massive clusters be bound only in galactic halos and interacting galaxies?

Even though all star clusters may form by the same mechanism—involving the gravitational collapse of dense cloud cores that are part of an overall hierarchical structure set up by turbulence—there is still a difference between bound and unbound clusters that results from a difference in the efficiency of conversion of gas into stars. If a high fraction of the gas goes into stars, then the mass that remains in the star cluster when the residual gas gets dispersed will be high enough to bind the cluster together gravitationally. If a low fraction goes into the stars, then the final stellar mass will be too low to keep the cluster bound for the relative speeds of the stars.

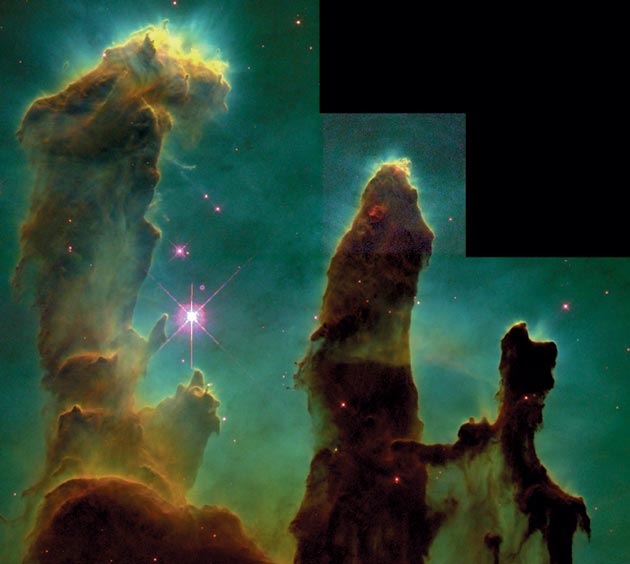

Star birth is a violent event, and the efficiency of star formation depends on how readily the young stars destroy the cloud in which they formed. When the gas finally collapses into a star, it drags in magnetic and turbulent energy, often forming a dense orbiting disk around the star. This disk stretches and shears the gas even more, pumping more energy into magnetism and turbulence. As a result, the stellar collapse builds up enormous pressures that get released in the form of flares, winds and jets. Some of these bursts probably resemble solar storms, but they are much more violent in a young star. A violent and irregular wind like this can disrupt the low-density gas around a star. Young, massive stars are also extremely bright and hot, and this radiation can heat the surrounding gas, causing enormous amounts of it to move away. As a result of all this activity, young massive stars push away the residual cloud around them, limiting the amount of gas available for new stars in that region.

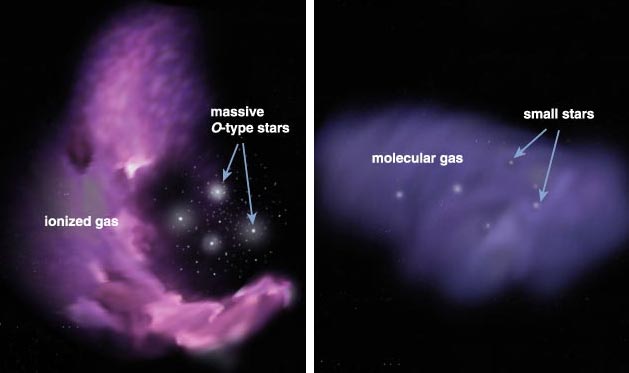

There seem to be two situations where star birth is not quite so disruptive, and then the efficiency can become high enough to allow a bound cluster to form. One arises for rather small clouds, where few massive stars get a chance to form. The Pleiades cluster, for example, probably formed in a small cloud because its total stellar mass is less than 1,000 suns. The other situation arises for clouds of any mass in extremely high-pressure environments. This is where globular clusters form.

An important component of this idea is the observation that massive stars are extremely rare. Stars that are massive enough to disrupt the surrounding cloud are not likely to appear in a cluster consisting of a few hundred stars. Perhaps only one in 1,000 stars has sufficient mass to be destructive. Small clouds, which form only a few hundred stars, can often survive the entire birthing process without getting destroyed, producing a small bound cluster.

In fact, all bound clusters in normal galaxy disks have total stellar masses less than several thousand suns. This is precisely the threshold dividing small clouds that are not likely to form massive O and B stars from large clouds that are likely to form such stars. All larger star groups either have or once had massive stars. These stars always lead to rapid cloud disruption in normal galaxy disks, and this causes the stars to disperse in the form of short-lived OB associations.

The formation of globular clusters, which are both massive and bound, requires a different environment. Globular clusters are so massive (100,000 suns or more) that they must certainly have contained massive OB stars when they formed. The relative fraction of high- and low-mass stars seems to be about constant everywhere, so it would be unlikely to have differed much in the early universe when the halo globulars formed. Indeed, the young globulars found in interacting galaxies contain massive stars. Many of these globulars are so young that the massive stars have not yet had time to evolve and explode as supernovae.

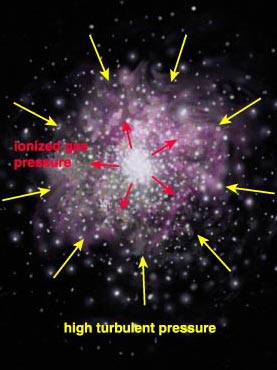

If massive stars are so destructive, what holds a cloud together as it forms a globular cluster? The key to this problem seems to be the way in which massive stars destroy their clouds. They do this primarily by heating the gas to a rather uniform 10,000 degrees Celsius, the temperature at which hydrogen (the main constituent) becomes ionized. During this ionization, the single electron in each hydrogen atom gets removed by an energetic photon. The electron typically comes off the atom very quickly, and the energy of motion from many such electrons rapidly heats the cloud, causing it to expand and disperse as an ionized nebula. The Orion nebula (M42) around the O stars in the young Orion cluster is a prime example. Once most of the hydrogen atoms in the region have lost their electrons, the stars can only heat the gas further after the atoms have recombined with their electrons. Then the gas and the stellar photons reach an equilibrium where photon heating and collisional excitation of atoms balance atomic cooling from the emission of low-energy recombination photons and other photons.

Gas at 10,000 degrees has a random thermal motion with a speed of about 10 kilometers per second. In normal galaxy disks, this motion greatly exceeds the escape speed of a star-forming cloud, so the ionized gas easily disperses the dense, cold gas. At very high pressures, however, all star-forming clouds of a given mass will have much higher velocity dispersions when they are in equilibrium with higher surface pressures.

If the pressure of the environment exceeds 1,000 times the local pressure in the interstellar medium near the sun, then clouds that are massive enough to make a globular cluster will have an escape speed greater than the thermal speed of ionized gas. In that case, the ionized nebulae formed by embedded stars will not readily disrupt the clouds, and star formation will proceed up to a high efficiency, even with massive stars. The result is a dense and massive bound cluster.

We can determine the pressure needed to produce a globular cluster in two ways. First, the clusters themselves tell us most of what we want to know, because they have an effective pressure today that is produced by the motions of their stars. This pressure is essentially GM2/R4 (where G is the gravitational constant, M is the cluster mass and R is the cluster radius). When we calculate these values for globulars in the Milky Way, we find that the pressures are 1,000 to 10,000 times that of the local interstellar medium. This pressure of stellar motion is a remnant of the pressure of the gas in which the stars formed.

Second, we can infer the pressure in the galactic halos at the time when the old globular clusters formed. This pressure must have been very large because all of the galaxy's gas had to have a very high velocity dispersion—comparable to the speed observed in today's galaxy rotations (200 kilometers per second)—in order to be in the halo in the first place. This is because a spheroidal gas cloud, like a young galaxy, has nearly isotropic random velocities, so the material can be carried against gravity to equal distances in all directions. This is very different from the present-day galaxy disk, which is thin because the gas velocities are low perpendicular to the disk, and much larger, because of rotation, parallel to the disk. With such fast random motions in the young galaxy, all of the clouds that formed by turbulent compression also had to be at very high pressures, easily exceeding 1,000 or 10,000 times the local interstellar pressure. The origin of this high pressure in the clouds was essentially the crashing and mixing of high-speed turbulent flows; the pressure inside and outside each cloud would equilibrate. Thus the globular clusters that formed in the young halos of galaxies were forged at extremely high pressures.

Courtesy of Harlow Shapley. Digital version provided by Knut Olsen, Paul Hodge and Don Brownlee.

In colliding galaxies the pressure is also high because the interaction causes gas to accrete into the central regions, where it ends up with an extremely high column density (a high mass per unit area in the disk). This accretion is driven by the loss of angular momentum through torques exerted on the gas by strong gravitational forces from spiral arms that are generated by the interaction. Because the pressure in any self-gravitating disk is essentially the gravitational constant G multiplied by the square of the mass column density, the pressure in these regions is also extremely high, again about 1,000 to 10,000 times the local value.

The young globulars in the Large Magellanic Cloud probably formed because this galaxy is interacting with the Small Magellanic Cloud (another satellite galaxy of the Milky Way). Every 100 million years or so the two Magellanic galaxies come close to each other, causing strong tidal forces to agitate the interstellar gas inside each galaxy. This increases the local pressure and causes the formation of young globular clusters. As it happens, the distribution of the ages for the observed globulars is consistent with the estimated collision rate between the two galaxies.

Young and old globular clusters form in essentially the same way as open clusters (such as the Pleiades) and OB associations (such as Orion)—in a hierarchical fashion dictated by turbulence in the gas within a galaxy. The key difference between globular clusters and open clusters is the ambient pressure in which they form. Whether a cluster was made 15 billion years ago or in a more modern universe, the basic processes of turbulence and star formation appear to have changed little.

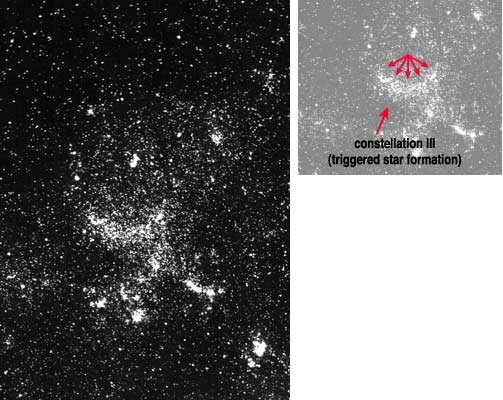

The hierarchical structure of gas described here may be responsible for the spontaneous formation of star clusters in all turbulent environments and at all epochs. But not all star formation is so free of environmental stimulation. There is another mode of star birth that follows the direct compression of gas by an outside source. This happens if there are hot young stars or supernovae to move the gas around, leading to the formation of new gas clouds out of low-density material, or to fast collapse and star formation inside pre-existing clouds.

There are many examples of such "triggered" star formation in our Galaxy and other nearby galaxies, including the Large Magellanic Cloud, where an arc of bright stars, 15 million years old, was triggered by pressure from a 30 million- year-old OB association located at the center of its curvature. The old association has long since dispersed, with only a trace of intermediate-mass stars and one Cepheid variable remaining. A third generation of stars formed later, as a big ring of clusters and nebulae that currently surrounds the arc. Similar arcs and rings of star formation have been seen in other galaxies as well. Some recent radio maps of the Large Magellanic Cloud and other small galaxies reveal so many holes and rings that their gaseous disks resemble Swiss cheese! We are now studying these regions.

The possibility of triggered star formation in galactic spiral arms is also under consideration. Spiral density waves explain well the regular spiral structure of spiral galaxies, but there is still a question of whether young stars concentrate in the spiral arms because most of the gas is there or because the spiral compression leads to some additional triggering. We have known for some time that the formation of stars in spiral arms is characterized by giant concentrations, somewhat equally spaced along the arms. Many of these are the star complexes that we discussed earlier. Such large-scale structure in a spiral arm is too regular to be fractal, and it may not be related to turbulence at all. Instead, it is probably the result of a gravitational instability in the spiral compressed gas.

In most locations, triggered star formation coexists with spontaneous star formation. Usually the triggering mode forms clouds that are turbulent and fractal on the inside, even though they may be regular in some way on the outside. Cluster formation proceeds inside the clouds as we have described above. This gives complicated but picturesque images, making the study of star formation interesting and challenging for a long time to come.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.