This Article From Issue

March-April 2001

Volume 89, Number 2

DOI: 10.1511/2001.18.0

Making Waves: Stories from My Life. Yakov Alpert. xvii + 260 pages. Yale University Press, 2000. $30.

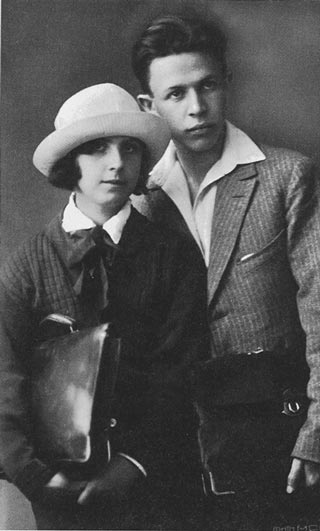

In Making Waves, Yakov Alpert, a pioneer in several fields of radio and space-plasma physics, provides a gripping firsthand account of life in the Soviet scientific community from the time of the Bolshevik revolution through the collapse of the Soviet system. This memoir, whose dust jacket features a sketch of Alpert gazing soulfully at the reader, invites comparison with Roald Z. Sagdeev's 1994 autobiography, The Making of a Soviet Scientist (which I reviewed for Sky and Telescope in December 1994, and which Alpert discusses in an appendix). Alpert's sincerity and cordiality in paying tribute to many of his scientific godfathers and colleagues, who were genuine heroes of Soviet science, stand in stark contrast to Sagdeev's penchant for self-advertisement.

From Making Waves

Under the totalitarian Soviet regime, Alpert did not receive even a small fraction of the decorations that were lavished on his fortunate contemporary Sagdeev, who was designated a Hero of Socialist Labor and won the Lenin Prize. Nonetheless Alpert led a distinguished life, one hallmarked by honesty. Despite the fact that he was stripped of any chance to expose his talent on a large scale during the prime of his career, Alpert realized his scientific gift, eventually achieved prominence and accomplished many things.

His life was extremely tough. He experienced the repression and unofficial anti-Semitism of the Soviet regime. Several times his activities were brutally discontinued; for example, he was expelled from the Institute of Physics. A general in the KGB (the Soviet secret police and intelligence agency) and others in the Communist hierarchy obstructed his path and tried to erase him from the history of science, but in the face of such challenges, he courageously stood by his principles. Finally he became a refusnik, a person forbidden to leave the country. Like Andrei Sakharov and many other Soviet dissidents, Alpert was deprived of his right to work in his profession. Yet even under such difficult circumstances, he remained a scholar and continued to do research. He held seminars in his home for years; more than 50 refusnik mathematicians and physicists participated, many of them notable representatives of the oppressed Soviet scientific community.

Although Alpert does not present an analytical overview of Soviet research, he does offer a sound, honest vision of the ups and downs, and the positive and negative aspects, of Soviet science, especially physics.

A proficient scholar, Alpert worked with a number of great physicists (among them some Nobelists) and scientific leaders, such as Pavel Alekseyevich Cherenkov, Semyon E. Khaikin, Peter Kapitsa [Pyotr Leonidovich Kapitsa], Sergei Pavlovich Korolyov [Korolev], Igor V. Kurchatov, Lev Davidovich Landau, Mikhail A. Leontovich, Leonid Isaakovitch Mandelshtam, Nikolai D. Papalexi, Sakharov, Igor Yevgenyevich Tamm and Sergei Ivanovich Vavilov. All are vividly featured in the book's pages, as are some engaging denizens of the art world. Unfortunately, most of these figures are not well known to American readers.

Alpert's lucid, thought-provoking view of Soviet physics will be of interest to a broad audience. Although he is not a historian of science, Alpert is an honest eyewitness to Soviet scientific development. The book's jacket includes enthusiastic praise from luminaries Arno Penzias, Joel L. Lebowitz and former Soviet dissident Yuri Orlov. Orlov observes that "Alpert's book is filled with historically priceless details hitherto unknown even to his fellow scientists because of the closed nature of Soviet society" and reminds us that "these details must not be lost."

Nowadays Alpert is a senior scientist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. This year he will celebrate his 90th birthday. On behalf of all his fans, from the bottom of my heart, I would like to wish him health and many more years of productive creativity.—Alexander Gurshtein, Astronomy, Space Research and History of Science, Mesa State College, Colorado

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.