This Article From Issue

March-April 2012

Volume 100, Number 2

Page 172

DOI: 10.1511/2012.95.172

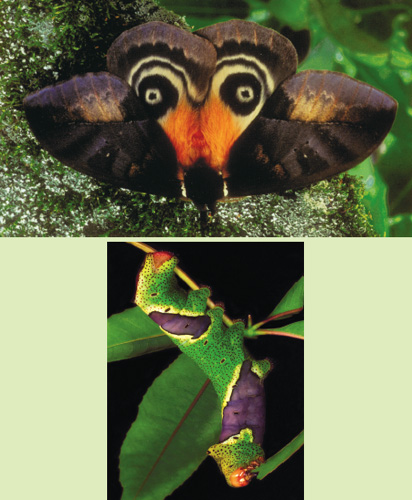

Last spring, the periodical cicadas emerged across eastern North America. Their vast numbers and short above-ground life spans inspired awe and irritation in humans—and made for good meals for birds and small mammals. Such snacks do not come without cost, however: Cicadas emit extremely loud shrieks when captured. Perhaps the pattern of the giant silk moth Citheronia azteca (below) evolved to resemble a cicada as a form of Batesian mimicry—imitation by a nonpoisonous species of a poisonous or unappetizing one. So Philip Howse speculates in Giant Silkmoths: Colour, Mimicry and Camouflage (Papadakis, $40 paper), in which he and photographer Kirby Wolfe showcase these members of the Saturniidae family.

Wolfe offers notes on collecting and raising silk moths. But the book’s wealth of photographs serves as collection enough: Viewing page after page of stunning moths from all over the world, I felt the guilty pleasure of seeing more of these creatures than one would ever normally encounter. Caterpillars are well represented also. The markings of the Titaea lemoulti caterpillar (below, bottom) break up the shape of its body, making it harder for predators to see.

Above (top), a male Automeris egeus moth displays its eye spots. Many silk moths’ eye spots look eerily like owl eyes. But the mimicry may not offer as much protection as one might hope. Howse notes, “There are reports of large numbers of saturniid moth wings, including those of the luna moth (Actias luna), beneath an owl’s nest.”

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.