This Article From Issue

September-October 2007

Volume 95, Number 5

Page 444

DOI: 10.1511/2007.67.444

The Cigarette Century: The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product that Defined America. Allan M. Brandt. viii + 600 pp. Basic Books, 2007. $36.

It is a bold move to give a book on the role of cigarettes in the 20th century the subtitle "The Rise, Fall, and Deadly Persistence of the Product that Defined America." Rise-and-fall stories, whether about empires, sports heroes, political leaders or business titans, make for a compelling narrative. But can a consumer product—one that "defined America," no less—serve as protagonist? That is the challenge Allan M. Brandt, a professor of the history of medicine at Harvard Medical School, sets for himself in his new book, The Cigarette Century. In it he tracks the emergence of smoking as a mass phenomenon in the United States, its growth to near-iconic cultural status and the increasing malevolence of its popular image toward the end of the century.

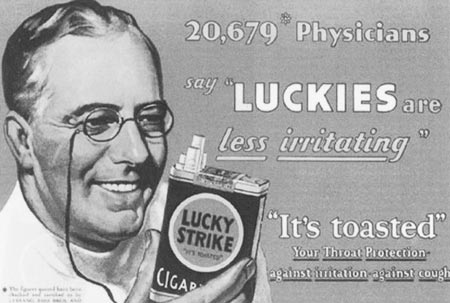

From The Cigarette Century.

Like any good yarn, the tale of the cigarette as it emerges from its early days—when it was the largely overlooked sibling of forms of tobacco use that were considered more manly (chew, pipes, cigars)—benefits from a larger-than-life figure, James Buchanan ("Buck") Duke. Duke, who "almost single-handedly invented the modern cigarette," was cut from the same cloth as the captains of industry who achieved a more enduring prominence at the start of the 20th century: He was salesman, entrepreneur and efficiency devotee; he had the vision to capitalize on new technology (particularly the automated cigarette-rolling machine); and he was driven by an unquenchable thirst for monopolization. Duke set the tone for an industry that would relentlessly seek new markets through inventive advertising in the early decades of the century. A particularly striking example of this was the promotion of smoking as a symbol of the liberated woman.

But the story line has its dynamic tension as well. From the outset, Duke and the burgeoning industry were challenged by antismoking advocates—a reform movement, partly energized by the health concerns of the Progressive era, but more strongly influenced by the moralizing impulses that animated the Prohibition era. Indeed, for a brief time, a sizeable minority of states enacted a ban on tobacco alongside the nationwide prohibition of alcoholic beverages. These moralistic strictures, however, soon ran their course, overwhelmed by an advertising strategy perfectly attuned to the pleasure-seeking ambience of the post-Great War era. In virtually every corner of American life, from the movies to the military, the cigarette would become a symbol of romance, relaxation and sociability.

And so things stood until mid-century, when a new and daunting challenge confronted tobacco companies: an emerging body of scientific evidence that smoking is unhealthful. Brandt carefully traces the scientific advances as research on laboratory animals and epidemiological studies of human populations steadily built the case for associating lung cancer, and later a host of other diseases, with cigarette smoking. Just as the cigarette broke new ground in consumer advertising, so did investigation of its health consequences bolster the authority of population-based studies of the etiology of disease. Indeed, the data collected in those investigations redirected the field of public health from its long tradition of focusing on infectious diseases.

From The Cigarette Century.

The landmark surgeon general's report of 1964 gave an authoritative stamp to the link between smoking and lung cancer, but the tobacco industry did not take the new science-based challenges lying down. Turning once again to advertising and promotion as a counterstrategy, the industry moved aggressively in two directions: With much fanfare, they introduced and promoted filter cigarettes, as well as mentholated and "lite" variants, in an attempt to undercut health concerns generated by the new scientific findings. At the same time, they went on the attack, vigorously recruiting scientific "experts" who claimed that the case for associating tobacco use with lung cancer had not been proved. More studies were necessary, the industry and its experts argued, before any causal inferences could be drawn (although, strikingly, they offered no studies as counterevidence).

Always creative, the industry also moved beyond the scientific "controversy" (as they labeled it) to create new images for the late-century smoker to identify with—most notably the Marlboro Man, a virile, independent "free spirit" evoking traditional American values, and Joe Camel, a "cool customer" designed to appeal to the urban smoker and to captivate children and teens.

Brandt skillfully weaves together the book's dual leitmotifs: pervasive and pathbreaking industry reliance on advertising to shape consumer demand, countered by challenges from antitobacco forces. The two sides were at loggerheads, and there would be no serious breakthrough in reducing the appeal of tobacco until the 1960s, when antismoking efforts in the legislative arena came to the forefront.

As tobacco entered the realm of politics, however, the industry once again proved to be an indomitable and ingenious foe. In the mid-1960s, Congress did enact a law requiring that cigarette packs must carry a warning, but it was exceedingly tepid ("Caution: Cigarette Smoking May Be Hazardous to Your Health") and was linked to a preemption provision that precluded any stronger measures by federal or state regulators. Soon thereafter, the Federal Communications Commission required broadcast media, under the "fairness doctrine," to counter cigarette advertising with health messages. In part because those antismoking spots were so effective, the industry eventually acceded to legislation eliminating all tobacco broadcast advertising and shifted its promotional resources to print media, sporting events and point-ofpurchase displays. As Brandt documents, the tobaccocontrol movement's efforts to get Congress to act proved to be a nonstarter; the industry, with its virtually unlimited resources and legislative contacts, simply overwhelmed the opposition.

But no amount of money could make the growing body of scientific evidence go away. Recognizing the threat, the industry leaned more heavily on another theme that resonated (like the rugged individualism of the Marlboro Man) with the American character: freedom of choice. This line of advocacy, however, which the industry trumpeted both in opposition to product regulation and as a defense to lawsuits, was not without risks; after all, the logical implication of freedom of choice was that there were reasons not to choose smoking. The smoker's right to opt for the pleasures of smoking was used as a trump card against both paternalistic risk regulation and injury claims. The strategy rested uneasily alongside the industry's continuing vehement assertions that no such risks had been established.

In the end, the fortress of freedom of choice proved not to be impregnable, but it fell for reasons entirely apart from its shaky foundation in logic. Two distinct lines of attack led to the industry's undoing in the realm of public opinion and hastened a precipitous drop in smoking rates, from nearly half of the adult population in the early 1970s to about 20 percent now.

One front addressed the health consequences of environmental tobacco smoke for nonsmokers. Again the industry waved the banner of "not proved." But in sharp contrast to smokers, nonsmokers with health-based claims could not be accused of having brought their affliction on themselves, nor could attempts to protect nonsmokers be branded as paternalism. By the mid-1970s, states and localities had begun to enact a wide variety of bans on smoking in public places, based on concerns about secondhand smoke that stood the freedom-of-choice argument on its head. Smoking was on its way to becoming a marginalized activity.

The second assault was aimed directly at the freedom-of-choice argument, focusing on the addictive character of nicotine. Ironically, it was not the pathology of addiction itself that proved devastating to the industry, but the internal business documents uncovered during pretrial discovery for various lawsuits, revealing that companies had manipulated nicotine content and were explicitly committed to rejection of evidence-based addiction studies.

Indeed, the irony can hardly be overstated. The documents have led to mixed results in litigation: a comprehensive multistate financial settlement of health reimbursement claims, but no breakthrough in class-action or individual lawsuits, in which the industry has more than held its own. More critically, the documents eventually yielded a mountain of much-publicized information on industry efforts not just to manipulate nicotine content, but also to obfuscate health-risk data and target vulnerable populations of potential smokers, especially impressionable young people. By the end of the 20th century, the emerging tale of hypocrisy and deceit had led to the perception that tobacco was an outlaw industry.

These documents serve as the foundation for much of Brandt's narrative—and not surprisingly, the book offers a harsh indictment of the tobacco industry (and, in a closing chapter, condemnation of the strategies companies are employing to recruit smokers in less-regulated markets overseas). In its particulars, Brandt's recounting of the place of smoking in American life and politics covers familiar territory for those who have closely followed the unfolding saga of tobacco over the past decade or have read previous historical accounts, particularly Richard Kluger's 1996 book Ashes to Ashes. But Brandt has an acute eye for the larger cultural and institutional dimensions of the tobacco narrative. And rather than organizing his material in a strictly chronological fashion, he wisely takes a multifaceted approach, portraying smoking as it has intersected with American culture, science and law. The Cigarette Century is thus a thought-provoking account of tobacco as a key defining constituent of life in America over the course of the 20th century.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.