Short takes on three books

By David Schneider, Brian Hayes, Greg Ross

How Everything Works: Making Physics Out of the Ordinary · Another Day in the Frontal Lobe: A Brain Surgeon Exposes Life on the Inside · The Structure and Dynamics of Networks

How Everything Works: Making Physics Out of the Ordinary · Another Day in the Frontal Lobe: A Brain Surgeon Exposes Life on the Inside · The Structure and Dynamics of Networks

DOI: 10.1511/2006.62.571

HOW EVERYTHING WORKS: Making Physics Out of the Ordinary. Louis Bloomfield. John Wiley & Sons, $40.

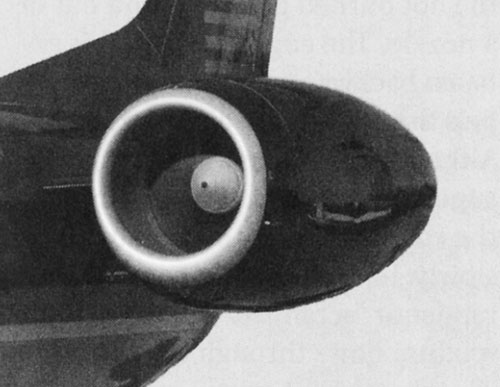

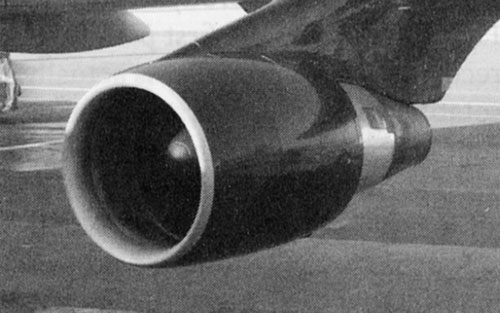

From How Everything Works.

Books on how things work often adopt a format that gives equal space to each device described. So the flush toilet, say, might get the same number of words devoted to it as the internal-combustion engine, even though the latter is far more complicated. In How Everything Works: Making Physics Out of the Ordinary, Louis Bloomfield avoids that trap by taking just as long as he needs to explain things. And that's exactly what he does, explain things, his chapters having such titles as "Things That Involve Light," "Things That Move With Fluids, "Things That Involve Chemical Physics" and so forth. The result is something of a cross between those familiar (and often less-than-satisfying) how-it-works guides and a full-blown physics textbook.

Although Bloomfield demonstrates considerable knowledge about the history of science and technology, his aim is clearly to explain how things work rather than how they were developed. Thus his treatment of the transistor very appropriately jumps straight to the field-effect transistor, which is fairly easy to understand, without first explaining its more complex predecessor, the bipolar transistor.

From How Everything Works.

Bloomfield also shows excellent judgment about how far to dive in. (One exception here is his cursory treatment of magnetic resonance imaging, a technology that is admittedly very difficult to explain in anything other than a superficial manner.) His section on the microwave oven, for example, helped me finally to understand how a cavity magnetron works. Bloomfield also straightened me out on the difference between a turbojet engine (above, right) and a turbofan engine (left), a distinction I hadn't at all appreciated. And he even clued me in on why the front fork of a child's bike isn't curved forward. All but the most hard-core technophile should find many similar moments of enlightenment in this delightfully informative book.—David Schneider

ANOTHER DAY IN THE FRONTAL LOBE: A Brain Surgeon Exposes Life on the Inside. Katrina Firlik. Random House, $24.95.

"Colloid cysts are fun to remove," writes neurosurgeon Katrina Firlik. "You have to have some fun with your job, or why do it?" Confronted every day with matters of life and death, Firlik is determined to take pleasure where she can find it, and her book offers a friendly, witty and remarkably candid tour through a brain surgeon's daily life.

Firlik describes her role as "part scientist, part mechanic," and her topics range from removing a nail from a carpenter's head to imagining future advances like the "brainlift," a memory-boosting technology worthy of a science-fiction novel. She illustrates her points with harrowing and often poignant tales from her own experience, leavening them with engaging asides on consciousness, evolution and the nature of mind.

It's a welcome perspective on a male-dominated specialty. Of the 4,500 neurosurgeons in the United States, only about 200 are women, and they are not always received gracefully. When Firlik was applying for a residency, one interviewer asked her, "How do you know you can handle all the big drills?" She meets these comments with admirable patience, crediting earlier woman surgeons "who must have had it harder—much harder—than I did."

That air of determined hopefulness pervades and elevates her story. Dealing daily with tumors and strokes can be depressing, she writes, but her familiarity with trauma has ultimately enhanced her appreciation of ordinary existence: "I've see people in every state of neurological decline and I've seen death, over and over again. And this makes me feel lucky about life, every day."—Greg Ross

THE STRUCTURE AND DYNAMICS OF NETWORKS. Edited by Mark Newman, Albert-László Barabási and Duncan J. Watts. Princeton University Press, $49.50.

The science of networks is in a golden age—or maybe one should call it a gold rush. Physicists, mathematicians and assorted others who study networks have been staking claims and digging up some bright nuggets of novelty. The boom began in the late 1990s, when methods of mathematical graph theory were first applied to very large networks, most notably the Internet and the World Wide Web. These structures were found to have some surprising patterns of connectivity; for example, they are "small world" nets, where seemingly remote nodes are linked by relatively short paths. Later investigations found the same properties in many other networks, from interlocking boards of directors in the corporate world to gene-regulation networks in the living cell.

Although the field is young, it seems there is now enough material to justify a retrospective volume of key papers. This collection, edited by three of the pioneers, reprints more than 40 contributions, placed in context by thoughtful introductory material. A few of the papers hark back to the pre-gold-rush roots of the field. One of these early works is remarkable: a 1929 short story by the Hungarian writer Frigyes Karinthy, which foreshadows the famous "six degrees of separation" experiments of Stanley Milgram. (One of Milgram's articles is also included.)—Brian Hayes

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.