This Article From Issue

January-February 2007

Volume 95, Number 1

Page 78

DOI: 10.1511/2007.63.78

The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More. Chris Anderson. xiv + 238 pp. Hyperion, 2006. $24.95.

If a book about the demise of the best seller becomes a best seller, does that undermine the book's credibility?

Chris Anderson's thesis in The Long Tail is that we have left behind the age when blockbuster movies, top-40 songs and prime-time network television shows determined tastes and habits. No longer do we all read the same books and magazines or listen to the same radio station. Although hits and best sellers still exist, they do not dominate the market or the culture as they once did. It's gotten harder to sell a million copies of one thing but easier to sell one copy each of a million things. "The mass market is turning into a mass of niches," Anderson writes. And yet, for all that, Anderson's own book is not a niche item. Within a few weeks of its publication, the title climbed into the top 100 books in the sales rankings tabulated by Amazon.com. (As it happens, Amazon sales rankings have a prominent place in this narrative; I'll return to them below.)

From The Long Tail.

Anderson argues that commerce has long been ruled by a mentality of scarcity: Physical and economic constraints have limited the variety of goods that could be made available. In the music department of a Wal-Mart, he counted the CDs on display and found only about 4,500 titles. A supermarket might stock 30,000 items, a large bookstore perhaps 100,000. Even in these "big box" stores, shelf space is a scarce and expensive resource. "Today, the average cost of carrying a single DVD in a movie rental store is $22 a year. Only the most popular titles rent often enough to make that back (there's a reason why they call it 'Blockbuster')."

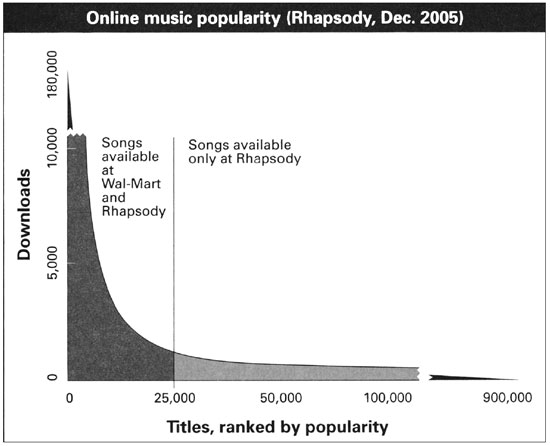

Technology is now breaking this bottleneck; there are improved efficiencies in manufacturing, warehousing and shipping, but the key innovation, of course, is the Internet. For online retailers, inventory costs are dramatically lower. Adding one title no longer means evicting another; there's room for everything. The bookstore at the mall may offer 100,000 titles, but Amazon lists 3.7 million. Contrast the 4,500 CDs at Wal-Mart with 1.5 million songs available through the online music service Rhapsody. A Blockbuster store might stock 3,000 DVDs, compared with 55,000 offered by Netflix. "For the first time in history," Anderson writes, "hits and niches are on equal economic footing, both just entries in a database called up on demand." We have arrived in a "paradise of choice."

But there is a subtlety in this calculus. Are those online retailers broader, or are they just bigger? Consider a hypothetical bookstore where the manager will carry any book that sells at least one copy a year. Now suppose we scale up this store by a factor of 10; the new store—call it Beyond the Borders—has 10 times as many customers, 10 times the shelf space and 10 times the total sales. If the manager maintains the same one-copy-a-year threshold, many more books will qualify for a place on the shelves. Should this expanded store be considered part of Anderson's "long tail" phenomenon? It's true that the larger store offers more variety; on the other hand, the overall shape of the sales curve is unchanged. If Harry Potter outsells Harold Pinter 100-to-1 in the smaller store, the ratio will remain the same in the larger one. There has been no shift in the tastes or preferences of the customers; it's just that there are more customers. This broadening of the market is an interesting development, but it hardly looks like a major social and economic transformation.

Anderson maintains that the changes he is describing are not just an effect of size—that the sales curve for Amazon or iTunes is not simply scaled up but also different in shape, reflecting a wider spectrum of interests. "There are still hits and niches, but the hits are relatively less popular and the niches relatively more so." In other words, the tail is not only longer but also fatter. (Look out, Harry Potter: Harold Pinter is gaining on you.) Unfortunately, quantitative evidence supporting this proposition is hard to come by. And Anderson gives short shrift to some of the most interesting evidence he has at hand—which takes us back to those Amazon sales rankings.

The Long Tail began not as a book but as a magazine article in Wired (where Anderson is editor in chief), and then it took on a second life as a blog at the Web site longtail.com. A major topic of discussion both in the article and on the blog was analysis of the ranking that Amazon assigns to every book in its online listings, with hourly updates. Authors obsess over these numbers but can never be quite sure what they mean. When I last checked, The Long Tail was ranked No. 240. Does that mean it outsold all but 239 other books in the preceding hour, or does the rank represent cumulative sales over some longer period? More important, what does the ranking reveal about the actual number of copies sold? Amazon won't tell, and so others have tried to calibrate the rankings by "reverse engineering." One technique is to place orders for a title and observe the effect on the ranking. For a book languishing near rank 600,000, buying five copies boosted the ranking to 4,467, though only briefly.

The point of this exercise is to discern the shape of the Amazon sales curve: the number of copies sold as a function of ranking. In the Wired article, Anderson concluded that 57 percent of book sales at Amazon.com come from titles ranked beyond 100,000. This estimate suggested that the tail is extraordinarily long and fat, providing an outlet for a vast assortment of works that in years gone by would never have found readers. After the article appeared, however, skeptics challenged the 57-percent figure; even Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon, disputed it. There followed a lively and thoughtful exchange of ideas at longtail.com.Relying largely on the work of Morris Rosenthal of Foner Books, Anderson eventually revised his estimate, suggesting that titles ranked beyond 100,000 account for between a fourth and a third of all books sold by Amazon.

Reading the spirited discussions at longtail.com gave me high expectations for the book version of The Long Tail. I was disappointed to discover that almost none of the ingenious "forensic economics" has survived the journey from blog to book. The main text carries just the bland assertion that "about a quarter of Amazon's book sales come from outside its top 100,000 titles." An endnote gives a perfunctory account of where this number came from but offers no quantitative clue to what it means. And the meaning is not at all obvious. Anderson emphasizes that the titles beyond rank 100,000 would not be found in a typical bookstore, but that fact alone doesn't prove that sales have migrated from the "short head" to the long tail. As noted above, some lengthening of the tail could be expected simply because Amazon is the biggest bookstore ever. To show that the tail is fatter as well as longer—that buyers have abandoned Potter for Pinter—we need to look at the mathematical form of the sales curve.

Regrettably, Anderson is not at his best when it comes to presenting mathematical concepts. He puts off discussing the matter at all until halfway through the book, then explains that the sales curve is a power law, which he defines as "a curve where a small number of things occur with high amplitude (read: sales) and a large number of things occur with low amplitude. A few things sell a lot and a lot of things sell a little." This statement isn't wrong, but it's singularly unhelpful. It applies equally well to any other plausible function for describing the sales curve, such as an exponential or a log-normal distribution. These alternative distributions are not mentioned in the main text, although they do turn up in an endnote. The note confuses matters further by suggesting that a power law is a kind of exponential. (It's not. In one case x is raised to a power; in the other, x is the power something is raised to.)

Does it really matter whether the sales curve is a power law or something else? If "long tail" is just a buzzword, perhaps not. But the term does have a specific meaning in statistics, where it refers to a distribution with infinite variance; what this comes down to, roughly speaking, is that in a long-tailed distribution even the most improbable events will probably happen. Unbounded variance is crucial to generating the endless variety of "niches" that Anderson celebrates. Only a power-law distribution has this property; more specifically, the distribution must be such that the abundance of the xth-ranked item is proportional to 1/x α, with α greater than 0 but less than 2. Determining whether or not these criteria are satisfied by a given data set (such as the reverse-engineered Amazon sales figures) can be a delicate undertaking, and estimating the numerical value of α is even harder. Anderson chooses not to pursue the question. And so, strangely enough, in The Long Tail we never really learn whether the tail is long.

Even if the mathematical underpinnings are lacking, though, Anderson may well be right about the waning influence of the hit parade and the greater scope for ideas without mass-market appeal. I hope so. I also hope he is not too disappointed that his own book has failed to escape the short head and find a suitable niche out in the long tail.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.