Sharing in Science

By Karen Louis, Lisa Jones, Eric Campbell

Are research results freely shared?

Are research results freely shared?

DOI: 10.1511/2002.27.304

Over the past two decades, one of the notable features of the landscape of science in the United States has been the growth of research relationships between academia and private industry. These arrangements have in turn been the subject of considerable research. But there have been few studies examining one aspect—the effects they might have on the sharing of research results in science.

Openness in the sharing of research results is one of the norms of modern science. The assumption behind this openness is that progress in science demands the sharing of results within the scientific community as early as possible in the discovery process. Scientists communicate their results so that others may build on previous work to move knowledge forward. Moreover, open communication lets other investigators challenge, verify and widely disseminate results. Yet it is also argued that some secrecy is necessary in science to protect intellectual property and govern the uses of the research. Previous research suggests that most scientists are actually ambivalent, believing in both openness and some secrecy.

In a recent survey, we looked at sharing and secrecy in the fast-moving field of genetics, where industry-academic collaborations are widespread. We wondered whether there is an association between faculty members' opinions about the importance and timing of sharing research results, and their relationships with industry. And we wanted to assess the consequences, both positive and negative, of prepublication sharing of research data or materials. We asked, for instance, whether the progress of individual research projects, or of students' careers, had been affected by the sharing or withholding of results.

A related issue is the degree to which scientists benefit personally and financially from their research. The increasing involvement of university-based scientists with industry over the past two decades raises different questions about openness and personal interest. Corporate sponsors of university research restrict early publication to protect their financial interests; university policies often support this practice to protect the university's right to patent research results. Individual faculty members are increasing their personal stake in the commercialization of their research as they become involved in new start-up companies or serve on industry boards of directors.

The population of geneticists used in the study was drawn from a stratified random sample of 3,000 respondents to a larger survey of university-based life scientists. The subsample of 1,820 members of genetics and human genetics departments used for this paper excludes people not currently active in research—clinical faculty members who had not published at least one article in the National Library of Medicine's MEDLINE database in the three years preceding the study. Of the qualifying sample, 50 percent are full professors, 28 percent associate professors, and 22 percent are assistant professors; 75 percent are male, and 25 percent are female. Respondents were administered an anonymous, largely closed-ended survey. The response rate for the overall survey was 64.5 percent. Key results are as follows:

Sharing research with other scientists

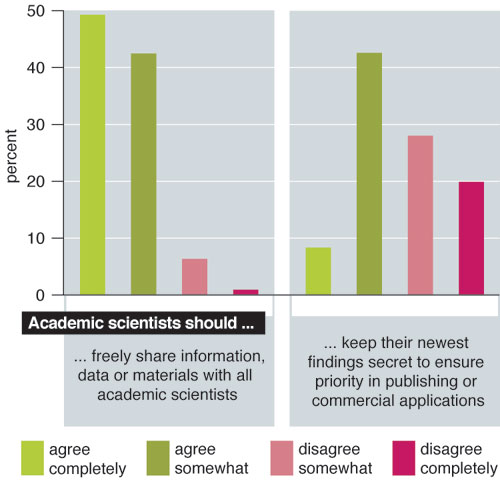

There is evidence of continuing normative ambivalence about openness and disinterestedness. Virtually all geneticists believe that scientists should share their results freely with all peers (49 percent "agree completely," and 42 percent "agree somewhat" on a 4-point scale) and should be motivated primarily by a desire for knowledge (73 percent "agree completely" and 24 percent "agree somewhat"). In addition, 68 percent indicate that they are personally "very willing" to share with other academic scientists. Nevertheless, a substantial proportion also believe that scientists should keep their newest findings secret to protect their priority (51 percent "agree completely" or "somewhat") and should also receive direct, personal benefits from their scientific discoveries (47 percent "agree completely" or "somewhat").

A significant proportion—approximately 30 percent—also report that, within the past three years, they have withheld research results from other academic scientists prior to publication on at least one occasion. The most common reasons given for withholding were to protect their own ability to publish (67 percent of those who withheld indicated that this was "very important") or that of their students (75 percent responded "very important"). In contrast, 21 percent indicated that it was "very important" to withhold to honor agreements with industry sponsors.

Practical constraints other than scientific priority or potential commercialization enter into the decision to share or not. More than two-thirds indicated that the extra effort involved in sharing prepublication results was a "very important" or "moderately important" factor in influencing their behavior. Distrust of other academics is also a salient issue for many. For example, 28 percent indicated that they did not share because they believed that others would not reciprocate ("very important" or "moderately important").

Sharing and relationships with industry

Most university-based geneticists—79 percent—have some financial relationship with industry. We asked respondents to indicate the industry roles that they had in the past three years that had potential for personal gain through financial remuneration (company ownership, service on a board of directors, consulting, etc.), and 35 percent reported one or more. We also asked about industry support for faculty work (grants, gifts, etc.), and 70 percent had received some professional support within the past three years. Nearly all of those who had personal-gain relationships with industry also had private research support.

Relationships with industry are weakly associated with attitudes about openness and personal interest. For example, there was no difference between those who have no industry relations and those who have them when asked about willingness to share "information, data or materials with other academic scientists," nor was there any difference between the groups regarding the importance of keeping their newest findings secret to ensure priority. The only area of difference is that those who had no industry relationships were more likely than their peers to "agree completely" with the statement that "academic scientists should be motivated by the desire for knowledge and discovery rather than by financial gain."

Relationships with industry are associated with more secretive behavior. We defined secretive behavior as self-reports that the respondent "usually" or "always" intentionally withheld pre-publication information from other scientists. Geneticists with industry relationships were somewhat (but significantly) less likely to share with their university peers and students than were scientists with no relationships or relationships that were limited to funding their university work. This includes venues such as seminars in their own departments, at other academic institutions and at professional meetings. We emphasize, however, that the percentage of faculty members that always or usually withheld information is a minority in all groups. For example, 12 percent of those with no industry relationships, 15 percent with professional funding, and 19 percent with personal gain relationships reported "usually" or "always" holding back at professional conferences.

The main disruption in scientific communication owing to secrecy and self-interested behavior is between university and industry scientists. The nearly 80 percent of faculty members who had any financial relationship with industry are less likely to share with their industrial counterparts than those who had no relationship (31 percent compared to 16 percent), and those who have personal-gain relationships are less likely to share than those with only professional support (34 percent contrasted with 29 percent).

What happens when scientists share their pre-publication results? Most of what we know to date consists of urban legends, most of which focus on "scooping" or losing scientific priority. Our survey shows that geneticists who have shared research information before publication report both positive and negative outcomes. For example, more than 52 percent indicated that sharing had led to collaboration and new publications, 41 percent said that it permitted them to perform research that would otherwise have been impossible, and 38 percent wrote new grants as a consequence. In contrast, 35 percent report being "scooped," 15 percent reported that a student's work had been compromised, and 15 percent indicated that they were impeded in efforts to commercialize their research.

Geneticists with industry relationships were more likely to experience both positive and negative consequences of sharing. To give some examples, 28 percent of those with no industry relationships reported being "scooped" contrasted with 40 percent of those with personal-gain relationships, whereas 2 percent of the former said that they were unable to commercialize their research compared with 7 percent of the latter. On the other hand, 41 percent of those with personal-gain relationships reported that sharing permitted them to perform research that would otherwise have been impossible, compared to 31 percent of those with no industry relationships, and 60 percent of the personal gain group said that sharing led to publications, compared with 43 percent of the no-industry relations group.

Our survey suggests that geneticists live with a complex set of personal beliefs about the ethical underpinnings of their work. They engage in multifaceted decision-making about both openness and personal interests in scientific research. On one hand, scientists are seen, as Robert K. Merton put it, as having "a passion for knowledge, idle curiosity, altruistic concern with the benefit to humanity." The search for scientific truths enables scientists to explore all information regardless of where it might lead. In contrast, the best scientists are often noted for their intense devotion to their particular line of inquiry: "Science ought to be personal to its core ? emotional commitment [as opposed to disinterestedness] can also be viewed as a necessary condition for the development of science," wrote Ian Mitroff in his 1974 philosophical study of Apollo moon scientists.

Scientists generally agree with the belief that the advancement of science is based on disclosure of results, but are usually discriminating about what to share, with whom and when. They believe that investigators should be motivated primarily by a desire for knowledge, but do not, generally, view this as inconsistent with the idea that personal payoffs from research results are acceptable.

Twenty years ago, when we first began to look at academic-industry research relationships, the involvement of private corporations in university research was generally regarded as a threat to basic research. Since then, accumulating evidence suggests that "hot fields" such as genetics have adapted with relatively few consequences to external and internal demands to monitor the effects of such relationships. This study puts some concerns to rest and raises others that deserve more discussion.

The results indicate that financial relationships with industry that involve research funding entail little risk to scientific openness and disinterestedness. There are no systematic patterns of either attitudes or behavior that indicate that this (now normative) relationship has negative consequences. Relationships that are also enhanced by the potential for personal financial gain do seem to increase the risk of secretive behaviors slightly, but the differences are relatively slight.

Two issues that deserve further discussion stand out, however. First, it is clear from the results that a very large proportion of geneticists—irrespective of the kinds of relationships they have with industry—deliberately withhold findings, methods and materials from their colleagues. The only groups from whom most scientists never withhold this information are students and postdoctoral fellows in their own departments. Secrecy, in one form or another, is the norm, despite protestations about the need for openness.

It is, however, also important to point to the "half full" finding that sharing continues to payoff for most of those who practice it. Those who share are able to reap the rewards of greater productivity and more rapid scientific advancement. The question that we cannot answer is whether this benefit accrues to open sharing (for example, at conferences), or, as we suspect, only to semi-public sharing within a small group of trusted colleagues.

Scientists need also to look at the reasons why more public openness may be declining, and to grapple with the fact that industry and commercialization are merely a small element of reluctance to share. We suggest that the following are more important than the corruption of individual work by the hope for financial gain:

Sharing is burdensome: Prepublication information needs to be "cleaned up" before it is shared, for reasons ranging from protecting scientific priority to protecting patients. The financial costs and time associated with sharing are increased, according to comments on the surveys, by increasing federal and university regulations, which are not factored into the increasingly competitive grants process.

Sharing poses real scientific risks: The "urban legend" of scooping is validated by this survey, in which over 30 percent of the respondents indicate that either their own or a student's intellectual work has been appropriated.

Sharing is undermined by decreasing trust: Scientists' experience is that even if they share, others may not reciprocate. Once denied by another scientist, will they be always gun-shy?

This research was sponsored in part by the National Human Genome Research Institute, Grant #1ro1hg01789-01.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.