This Article From Issue

July-August 2007

Volume 95, Number 4

Page 359

DOI: 10.1511/2007.66.359

The Lie Detectors: The History of an American Obsession. Ken Alder. xiv + 334 pp. Free Press, 2007.

The lie detector, or polygraph, is a true icon of modernity. Packaged in a small James Bond-like suitcase, it is nothing more than an elegant assembly of some basic medical technologies that measure blood pressure, heartbeat, breathing and sweat. Plug it into the wall, though, and voila!—a machine that can, it is claimed, detect human lies by bypassing the manipulative mind and registering the involuntary bodily signs that often accompany deception.

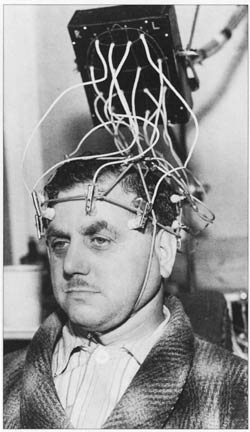

From The Lie Detectors.

The lie detector straddles some of the deepest fault lines in modern culture: between body and soul, mind and matter, human and machine, public and private. Not surprisingly then, pundits have warred long and hard over it. Does it really detect lies? A great deal of data have been assembled through the years in support of the proposition that it does, and an equally large amount has been arrayed suggesting that it does not. Should the lie detector be used? Many have said yes, but only if the machine has been proved totally reliable. Many others have said no—especially if it has been proved reliable! Accurate or not, this is a formidable technology. Thus, despite having been debunked by scientists and denounced by moralists, the polygraph has been embraced by government and big business as a powerful tool of social control and surveillance. The legal system has been ambivalent: The police have routinely used the device to navigate investigations and to secure confessions, but the courts have firmly rejected lie-detector results as legitimate evidence.

Ken Alder's new book, The Lie Detectors, provides us with the first good history of America's convoluted love-hate affair with this machine. Alder, a historian of science at Northwestern University, is careful not to join the pundits' wars and argue for or against the technology. He knows that the detector itself is only one part of the story. A second, indispensable, element is the human operator who conducts the interrogation and interprets the machine's recorded output; whether people perceive the operator as trustworthy strongly affects their willingness to accept the technology. A third factor is the interrogated subject; the more firmly he or she believes that the machine works, the more anxious he or she gets—and the more successful the machine and its operator are. Finally, consider wider society and its attitude: Most countries banned the technology, after all; only America fell in love with it. Why?

Alder does not care for dogmatic answers. Instead he offers us a rich history, organized around the careers of the individuals who conceived, developed and marketed the lie detector. He does not shy away from discussing larger questions about the culture that embraced the machine and allowed it to flourish, but he patiently waits until the developments in his story beg such discussions. The result is a fluent tale, personal yet pensive, well researched yet far from stuffy. This is Alder's distinct style, and it has made him one of the very few academic historians of science who have been able to cross over and attract large numbers of lay readers.

Alder's account begins with a story from the early 1920s, an era that begat various psychological inventions such as the I.Q. test and scientific industrial management. Americans became convinced that science and technology could provide answers to all social problems. In Berkeley, California, the local chief of police, August Vollmer, was leading a campaign that would soon sweep the nation, calling for a more humane police force and a more policed society. As someone who kept abreast of advances in science, Vollmer was especially keen about the new experimental techniques developed by psychologists to detect deception. Thus he took an interest when a rookie cop, John Larson (the first policeman in the nation to earn a doctorate—in physiology), came up with a "cardio-pneumo-psychograph" and used it to interrogate suspects in campus crimes. (Larson had gotten the idea from reading articles by William Marston, a Harvard psychologist and lawyer who was doing experiments to determine whether changes in systolic blood pressure accompanied the telling of falsehoods.) Vollmer was initially skeptical about Larson's device but eventually became an enthusiast and got Leonarde Keeler, the teenage son of a friend, interested as well. It was Vollmer's idea that Keeler would improve the instrument mechanically while Larson validated it scientifically, and he encouraged both young men to put the machine into practice in investigations conducted by the police. Thus was born the modern lie detector—conceived in the psychology laboratory and baptized at the police station.

Larson's and Keeler's stories make up the bulk of the book. Larson was a scientist of unyielding integrity, a relentless seeker of scientific truth and a bitter foe to all charlatans. Keeler, the son of a poet, was quite the opposite: an amateur magician and a ladies' man.

With Vollmer's blessing, Larson took lie detection to the capital of crime, Al Capone's Chicago, and Keeler followed him there. But their roads soon parted. Larson went to medical school and pursued a career in forensic psychiatry. He looked for true knowledge and spent his life trying to use his machine in the service of impartial science. Keeler, who knew better than to search for truth, looked for money and fame; he spent his life fighting injustice for the right price.

Both men were haunted by their invention, for each found deceit wherever he went. Larson found it hidden not only in his mental patients but also at the heart of the scientific establishment he so cherished. He blamed Keeler for prostituting their invention and turning it into a monstrosity, and he died bitter about not having attained the scientific recognition he desired. Meanwhile, Keeler played the machine for all it was worth, becoming America's most famous polygrapher. But he too found deceit, not only in the criminals he interrogated but also in the heart of the only woman he ever loved. Crushed, he turned to alcohol and died young.

Marston also plays a leading role in Alder's history. A tireless self-promoter, he offered his services to the legal system, wanting to assess witnesses' veracity with his technique. Turned down, he moved on to other cultural domains. He teamed with Madison Avenue to test the psychological responses of consumers to particular brands of cigarettes, shavers and razor blades. Later he moved to Hollywood, where he measured viewers' emotional reactions to specific movie scenes. None of these ventures proved a sweeping success, but Marston finally found fame and fortune in the collective imagination of comic-book readers, inventing Wonder Woman, the first female superhero, who was equipped with a magical golden lasso that compelled obedience and forced people to tell the truth.

As we follow Alder's protagonists through police stations and movie theaters, courts of law and of public opinion, psychology and crime labs, sensational trials and private bedrooms, newspapers and comic strips, we are gripped by this tale of a dark American obsession with truth. "We are a nation of sentimental materialists," Alder concludes. In the words of G. K. Chesterton's fictional detective, Father Brown (quoted by Alder), "Who but a Yankee would think of proving anything from heart-throbs? Why, they must be as sentimental as a man who thinks a woman is in love with him if she blushes."

Truth, in the end, is a funny thing. For even when we stumble upon it, how can we be sure that it is the truth? And even if we are sure of it, how can we convince others? In our technocratic age we long for a machine that could cut this Gordian knot—that would certify the truth and make it objective. But we should be careful what we wish for. Private honesty and public rationality are fine democratic ideals, but to expect a machine to produce them is clearly absurd.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.