Depicting a Fragmented World

By Julie Sperling

Mosaics provide a window into the Anthropocene.

Mosaics provide a window into the Anthropocene.

I remember exactly when it started. I was going through the daily batch of news clippings at work when I clicked on an article about how some climate trend or other was much worse than scientists had anticipated. That I can’t recall the exact trend is quite telling. I half-heartedly skimmed the article, eyes glazing over, thinking, “Yeah, yeah, I know it’s bad . . .” And then I stopped. Here I was, an environmental policy analyst with Environment and Climate Change Canada (the Canadian equivalent of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency)—someone whose day job centered on being informed about and invested in these topics—and I had reached the saturated, eyes-glazed-over point with the seemingly endless stream of articles about environmental collapse. And if I had reached that point, how were other people supposed to care?

Julie Sperling

As fortune would have it, though I was a bureaucrat by day, I was also a budding mosaic artist by night, and at that point in time I was searching for the big “Why?” that would be the focus of my art. The timing couldn’t have been better, and right then and there I decided I would make art about climate change as a way to help myself and others engage with the subject. And thus my climate change series “Fiddling While Rome Burns” was born. Since that day six years ago, my art has focused exclusively on climate change and, more recently, the Anthropocene—the epoch defined by the human-altered environment.

As it turns out, what began as a gut feeling and a personal reaction is backed by a significant body of research debunking the deficit model of science communication, a one-way approach in which scientists share their research with the “information deficient” public (see “How Climate Science Can Lead to Action,” January–February). The supposition is that people make poor decisions about climate change or other contentious matters because they just don’t know enough. Yet despite ample evidence that simply giving people more facts doesn’t work to change their minds, we continue to try it, believing that if we could just explain climate change or other issues better, or if we could find that one killer fact, we’d somehow convince them to care. As a bureaucrat (yes, I’m still leading a double life all these years later), I get it. Trying to sell something tangible such as an information campaign to my bosses would be infinitely easier than explaining that we need to invest in art in order to reach people on an emotional level.

Art is subjective, messy, and unpredictable. But it’s also an essential part of the dialogue surrounding the climate emergency and the overall collapse of our planetary life support systems. Research has shown that engaging with people based on shared values and experiences can be far more productive than the give-them-more-facts approach. Art, given its subjectivity, can provide a platform for these more tailored, intimate conversations, meeting people where they are and gently nudging them forward. And artists of all mediums around the world are increasingly taking up this challenge; we each approach the topic in a different way.

Personally, I use the medium of mosaic to talk about these big issues. I am, of course, biased, but I think mosaic has a few tricks up its sleeve that make it a very powerful medium with which to explore climate change and the Anthropocene. One of mosaic’s biggest strengths is that it is so materials- driven. My material of choice is stone, but I’ll use almost any material that will help me tell my story, including bullet casings, bones, plastic bags and utensils, e-waste, my old boots, and so much more. If I can cut it, it’s fair game.

Beyond the visual aspects of a material (including its color, texture, and reflectivity), the most important part for me is the meaning behind it and what I can say with any given material. I work with coal and shale a lot, making beautiful things out of “dirty” materials. I use them for their direct meanings—for instance, using coal in a mosaic about black carbon—but I also use them as proxies for the fossil fuel industry and greenhouse gas emissions more generally. I have also used shells that I submitted to my own homemade ocean acidification simulation wherein I stick them in vinegar to degrade them, and I have made an entire mosaic out of just white plastic to highlight the problem of ocean plastic pollution. I used cans of Budweiser and Spam in another piece inspired by the trash that the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration found in the Mariana Trench (see image above). Using these materials allows viewers to get up close and personal with substances they may not encounter in their everyday lives (such as coal) or to see ordinary materials in a different light (the shells, plastic, or beer cans) and connect them with bigger concepts and problems.

Another powerful tool that I employ in my work is what mosaicists call andamento, which refers to the lines, movement, and flow of a mosaic. It’s how we put all those hundreds and thousands of pieces together to tell a story. The ancient Romans set out rules for the composition of a mosaic, but contemporary mosaicists take these classical rules and bend them, break them, and sometimes invent new ones altogether. Composing a clear narrative in any given mosaic requires a dance between the materials and the andamento.

Julie Sperling

In depicting ocean acidification, I created the image of a degrading shell, where the andamento in the middle was very classical, tight, and whole (see image above). Then I started introducing little glitches in the lines—pieces just slightly out of place—that become bigger and more frequent as the spiral moves outward, until at the very edge it is a very loose, somewhat chaotic andamento. This message is reinforced by the shells themselves, which are also intact in the center, and, like the andamento, become increasingly degraded moving outward, with the ones on the edge having sat the longest in the vinegar.

Another of my mosaics is inspired by reports I read about the global state of soil (see image below). I wanted to convey just how thin, vulnerable, and valuable our layer of topsoil is. I created a 15-centimeter-thick band of deep rich brown, representing the topsoil. The use of a relatively classical andamento evokes layers of slow accumulation of this precious resource and serves to provide a point of contrast for the degradation that follows in the rest of the mosaic. The materials transition to red brick and terracotta, and the andamento moves away from lines of precisely cut cubes toward a more chaotic, aggressive style made up of larger, more random pieces to mimic cracked, parched earth.

Julie Sperling

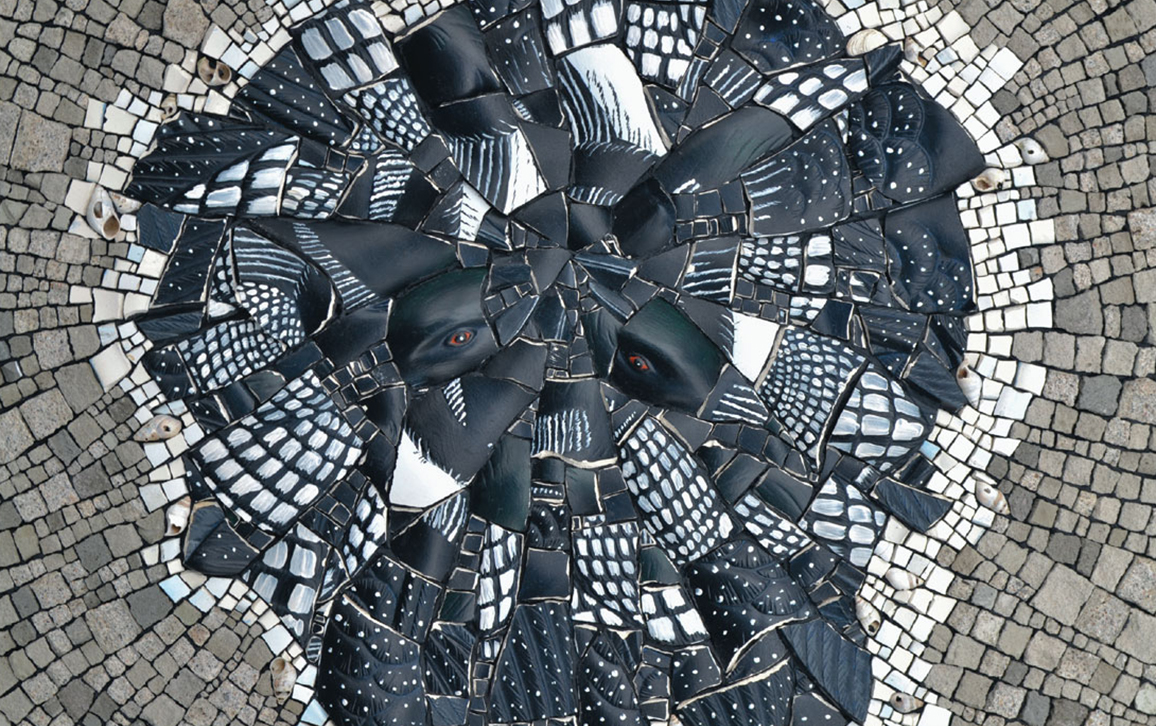

Finally, in telling the story of the mass extinction currently threatening many species, I created an explosion out of a broken ceramic loon against a background of traditional andamento made from concrete foraged from the side of the road (see image below). Again: two different styles of andamento, two different materials imbued with meaning. By using the official bird of Ontario (my province)—the common loon—I endeavored to make the message hit close to home for people: Loons are not among the animals we tend to associate with extinction, yet their populations have been declining for several decades. The concrete background is a nod to how changes in land use, such as urbanization, are a driving factor in this biological annihilation. And staring straight out from the center of the piece are the loon’s haunting red eyes, challenging the viewer to hold its gaze and not look away.

Julie Sperling

One of the strengths of mosaic is that people slow down and spend time with it, because it can be explored on so many levels. Viewers can study its textures and its geographies, they can examine individual pieces of a material, they can follow a line of andamento start to finish, they can take in the entire composition . . . Being able to hold people’s interest and curiosity on several timescales provides me with an opportunity to engage and tell a story. More often than not, that story is told in an abstract way. For me, that approach has been the best way to wrap my own artistic brain around these massive and complex issues. It is also a way to communicate that isn’t too preachy or didactic (which can be off-putting) and that doesn’t offer easy answers, because there are no easy answers to these challenges we’re facing. Abstraction allows me to start a dialogue through art and create space for contemplation, questions, and emotion.

I don’t want to alienate the viewer, so I try to walk the line between beauty and destruction. At first glance, I want my work to welcome people, to make them feel comfortable, to encourage them to spend time with my work. But as they are drawn in and begin exploring the mosaics, I want them to realize that something is amiss. That’s a beautiful shell, but . . . why are those other shells so corroded? Those are incredibly delicate, lace-like tendrils, but . . . they’re made from plastic? (See image below.) That black and white part looks so quilt-like, but it’s a jumble of bird, and it won’t stop looking at me. As an artist, I think that place of gentle discomfort can be a very productive one for the viewer.

Julie Sperling

Though I didn’t know it when I set out on this path, I have come to understand just how powerful mosaic can be as a medium for depicting complex global challenges. I started this body of work to fight disinterest and apathy, and over the years I’ve had the pleasure of hearing from people about how my art has expanded their awareness or changed their actions. However, all that quiet time in my studio, slowly, painstakingly putting each mosaic together piece by piece, has also ended up creating space for me to contemplate and wrestle with these issues. In working to engage others, I have also managed to re-engage myself.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.