This Article From Issue

March-April 2021

Volume 109, Number 2

Page 120

LAZY, CRAZY, AND DISGUSTING: Stigma and the Undoing of Global Health. Alexandra Brewis and Amber Wutich. 270 pp. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019. $34.95.

In settings ranging from global health projects to general medicine, well-intentioned practitioners often demean those they seek to help. Health workers may infantilize adults by telling them simple health truths they already know; they may project contempt toward a person simply for having been born into a setting or way of life that the individual is powerless to change; or they may use shame as a tactic for changing behavior. Lazy, Crazy, and Disgusting: Stigma and the Undoing of Global Health examines the effects of such practices in three quite different areas—obesity, mental illness, and domestic sanitation—devoting a section to each. Vignettes of victim-shaming are combined with discussions of health-shaping practices and social psychological research on health norms and the impact of stigmatization—labeling that can leave a person feeling unvalued, undesirable, or unwanted. For obesity, the label is “lazy,” for mental illness it is “crazy,” and for lack of sanitation it is “disgusting.”

The book provides an accessible, synthetic, and critical examination of the health effects of shame and stigma, one that was already long overdue when the book was published in 2019. That was before the onset of the current pandemic. The topic is of even more pressing concern now, when the public’s health depends so much on the behavior of individuals.

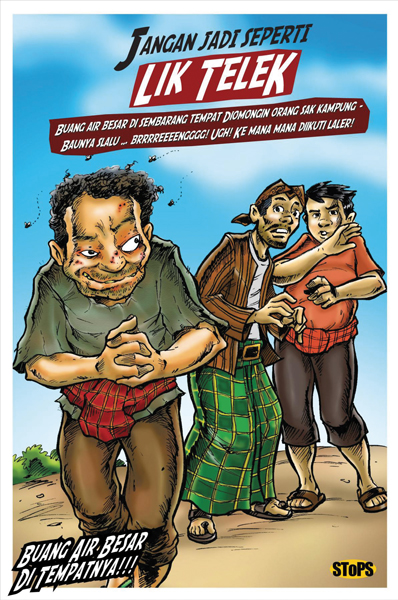

The authors, medical anthropologists Alexandra Brewis and Amber Wutich, explain that they conceived the project that resulted in the book in response to practices used in Community-Led Total Sanitation programs in Bangladesh and elsewhere. Such programs discourage open defecation by representing it as “disgusting,” hoping that this shaming will encourage communal investment in sanitary infrastructure such as toilet blocks and piped water. Brewis and Wutich note that these blame-laying approaches, which often ignore the constraints imposed by a lack of resources, have adverse effects on communal relations and the self- esteem of individuals. Such practices are ineffective, they argue, and may undermine the success of the projects.

From Lazy, Crazy, and Disgusting

In highlighting the counterproductive nature of some well-intended approaches, the book makes a legitimate point. But as I will try to show, that point is a limited one. It is impossible to avoid admonition in public health, and it is as important to explore ways of bringing about positive change as it is to avoid measures that are counterproductive.

Often Brewis and Wutich state their conclusions in strong terms, declaring, for example, that “Shame in all its forms needs to be removed from the public health tool kit, because it too easily misfires.” But then will come a caveat—in this case, “at the very least until the social stigma and longer-term impacts . . . are adequately tracked and addressed.” They recognize handwashing as “a pragmatic, central goal of global public health,” but they want readers to appreciate that shaming people for not washing their hands has a “dark side,” because it can result in the dehumanization of people unable to access soap and water.

In addition to exploring the harm done by shame, the authors campaign for a research agenda that is too often neglected: the integration of cultural social science into public health development projects and into health care institutions more generally. They call for fuller development of stigma epidemiology, which would lead to routine preparation of “stigma impact statements.”

They recognize some of the reasons such integration seldom takes place. Funding agencies give preference to projects tackling well-focused problems that can be addressed quickly and have clear, near-term outcomes; idealistic researchers, committed to change, have those same priorities. But if they lack insight into the local culture, researchers and health workers will find it difficult to get a sense of what it might be like to walk in the shoes of the residents even for a day, much less a year or a lifetime. They may instead resort to a simplistic, demeaning response: “That’s bad; don’t be that way.”

A book such as this, aimed at the general reader and focused on the harm done by health-shaming, cannot be expected to explore thoroughly the methodological problems involved in measuring that harm. The authors ask, “Is sanitation for all worth the painful, damaging humiliation and rejection of some?” The question is not merely rhetorical, and if stigma assessments are to be integrated into health planning, costs and benefits will need to be measured. As matters of social science methodology, the difficulties in performing such evaluations are formidable—they involve arriving at definitions, choosing means of measurement, agreeing on null hypotheses, controlling confounding factors, and so forth.

Similar difficulties arise in assessing the effects of admonitions in individual lives. I am thinking about null hypotheses when I assess my diet and exercise regimen: Even if I have lost no weight, might I have gained more weight without the regimen? Professional ethics are implicated too. One expects truth-telling from a clinician. At my dental checkup, I want the hygienist to chastise me if I am flossing haphazardly. Do I floss more diligently after being chastised? Perhaps. Response to shaming is not an either/or matter. I may respond more positively to one messenger than another, even when the message being delivered is the same.

The integration of cultural social science into public health development projects and into health care institutions more generally is too often neglected.

For Brewis and Wutich, shaming and other forms of stigmatization reflect the “powerful moral overtones” that pervade public health, and that fact dismays them. But a moral commitment has been and remains central to a field committed to progressive change; their book is itself an example. They say surprisingly little about the differing moral situations in the three domains they have chosen to discuss. With regard to sanitation, an area in which behaviors affect the transmission of infectious disease, a case can be made for admonitions, but that is not so in the realm of mental illness—there can be no warrant for heaping shame on people who may already see their lives in terms of what they are not able to be. The authors imply that obesity is, in principle, subject to personal choice in the same way that hygienic behavior is; but they go far to represent obesity as intractable, and they emphasize the difficulty of losing weight. They maintain that antiobesity efforts that “aren’t overtly blaming or shaming” may nevertheless be objectionable because those efforts “fully embrace the idea of individual responsibility in ways that likely reinforce stigmatizing beliefs.” If, as that statement implies, “individual responsibility” does not affect health, then admonitions are clearly moot. However, in many cases (in lifestyle-related diabetes, for instance) individual responsibility clearly does play a role.

And if we jettison admonition, what’s left? The authors tend to see health education (on the risks of tobacco, fast food, sugary drinks, and the like) as “soft stigma.” In focusing on what to avoid, they overlook deeper questions of how health-related behaviors and sensibilities are shaped. The social science their book presents is mainly empirical, consisting of surveys relating feelings of shame to various variables. The chief theorists on whom Brewis and Wutich rely are the anthropologist Mary Douglas and sociologist Erving Goffman, who produced half a century ago work that remains seminal, particularly for shedding light on shame, a term often used in a way that conflates the expression of admonition with the dehumanizing abjection and hopelessness that may result from admonition. Those are two separate things, and it is the latter that is the real concern here.

The insights of both of these theorists are more ambiguous and unsettling than Brewis and Wutich acknowledge. They agree with Douglas’s hypothesis that “hygiene stigma” is about maintaining “statuses and boundaries” rather than infection-avoidance, but they stop short of recognizing, as Douglas did, how important those statuses are. For Douglas, internalizing a sense of shame was concomitant with community life and helped communities avoid unresolvable conflicts. Brewis and Wutich cite Goffman’s stark descriptions of the routine dehumanization of patients in asylums, but they ignore his exploration of the power roles that can transform an empathetic and stigma-deploring trainee attendant into someone whose professional identity is predicated on the dehumanization that results from the separation of “us” from “them.”

Can and should we hope to escape shame? Even in a world where global media shape identity, shame remains powerful in community interactions. It can be a tool of liberation, sanctioning the claim for bodily autonomy in the #MeToo movement. And I believe that it can have value as a tool of public health: “You ought to be ashamed” is a correct response to people who refuse to wear a mask during a pandemic, asserting their right to exhale viruses into others’ faces.

As Brewis and Wutich admit, it is difficult to destigmatize health practices. Nevertheless, they do offer some options for promoting health that avoid creating stigma. Instead of using stigma to keep people with contagious diseases at a distance, you can give them paid sick days that allow them to stay home from work, or you can put them in hospital isolation units. You can carefully craft the language of public health messaging to eliminate stigmatization. You can teach providers how to use empathy to improve provider-patient communication and rapport. And with input from anthropologists, you can individually tailor global health programming for each local community. Obesity can be addressed through structural changes, such as making cities more walkable, eliminating food deserts, and addressing poverty.

Lazy, Crazy, and Disgusting often pits the individual against social forces. An alternative focus on humanization within communities might reveal that in a setting where autonomy is valued, admonition and judgment could act to transform complacency and fatalism into realistic aspiration and greater self-esteem.

As a historian of public health influenced by Goffman and Douglas, I am struck by some cases in which shaming has worked. Over time, it proved effective in antispitting campaigns for controlling tuberculosis. A “soft stigma” regarding diet and lifestyle followed publication of the results of the Framingham Heart Study, and it improved heart health. Shaming played an important role in the great sanitary revolution of the 19th century, when people came to envy and want to emulate those who had running water and toilets. The success of that revolution required not just adequate finance, effective technology, and strong leadership, but also realistic aspirations to have better and healthier lives. Brewis and Wutich recognize, but in my view do not sufficiently emphasize, the great extent to which social and economic circumstances determine whether admonitions are demeaning or constructive. Social epidemiologists following in the footsteps of Richard G. Wilkinson and Ichiro Kawachi have demonstrated that the stress and helplessness that accompany even the perception of inequality are themselves detrimental to health.

When I follow my dog, plastic bag in hand, shame is my guide. I am following Immanuel Kant’s categorical imperative of acting as I wish all would act. I am reinforcing community. Yet the guarantor of my self-esteem and respectability is ultimately that bag. And it is only by accident of circumstance that I need not use it for my own wastes, as residents of many shantytowns around the world must do. Like me, they are seeking cleanliness and embodying community by doing so.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.