This Article From Issue

September-October 2005

Volume 93, Number 5

Page 454

DOI: 10.1511/2005.55.454

Gravity's Shadow: The Search for Gravitational Waves. Harry Collins. xxiv + 870 pp. University of Chicago Press, 2004. Cloth, $100; paper, $39.

A reader who has avidly followed the popular science of the last decade could be forgiven for forgetting that physics is an experimental science. Strings, evaporating black holes, higher dimensions, supersymmetry and quantum gravity are all beautiful ideas, but we should never forget that so far they are only ideas. They make for great reading, but I sometimes wonder how many of the books and papers I have devoured in my efforts to keep up with the latest trends in particle physics will be worth reading 10 years hence.

The whole point of science—and the feature to which it owes all its success—is that no idea is to be believed until it has been rigorously tested by experiment. Thus it is worrying that these days many theorists spend their whole careers on ideas that are untested experimentally.

But if all is not well with theory, at least experiment must be healthy. After all, experiment is a simple thing: Just as in high school, you follow the procedure, and you either get the result predicted by the theory you are testing or you don't. Given enough resources, how could this approach fail? And, although you wouldn't know it from the popular literature, hundreds of millions of dollars a year are spent on experimental physics—much more than is spent on theory.

But despite the several billions invested in particle accelerators and detectors, there have been few truly major experimental discoveries in fundamental physics in the past 20 years. The fields that have continued to amaze are astronomy and cosmology, which are obviously healthy. But the only major addition to our knowledge of the elementary particles these past two decades was the discovery that neutrinos have mass. The list of new particles or effects that have been looked for—and so far not found—is longer: the Higgs particle, supersymmetric particles, dark-matter particles, proton decay, the fifth force, evidence of extra dimensions.

It is, then, very timely that Harry Collins has written a first-class study of how contemporary experimental physics operates. Collins is a distinguished sociologist, and in Gravity's Shadow he demonstrates why it is important to go beyond superficial characterizations of science to study how groups of scientists actually work together and make decisions. Collins has taken as his subject the search for gravitational radiation.

Gravitational waves are ripples in the geometry of spacetime, analogous to electromagnetic waves. Just as moving charges and magnets produce light waves, masses when they accelerate inevitably produce waves in the gravitational field—a field that, as Einstein discovered in working out his theory of general relativity, is exactly the same as the geometry of space and time.

The existence of gravitational waves (unlike that of strings or extra dimensions) is undoubted by experts. The waves are a consequence of the basic physical principles that go into Einstein's theory of relativity—principles that have been precisely tested in numerous experiments. Moreover, the effects of these waves have been seen: Two stars orbiting each other radiate gravitational waves. As a result, they lose energy and spiral in toward each other. For most binary star systems this decay happens very slowly, but for neutron stars, which are extremely compact and dense, and can orbit very close to each other at close to the speed of light, the effect is significant. Moreover, the radio pulses astronomers detect from some spinning neutron stars can be used to track the decay of their orbits. A major triumph of the general theory of relativity is that its predictions of how fast orbiting neutron stars lose energy by radiating it away in gravitational waves have been confirmed to an accuracy of many decimal places.

Of course it would be much better to observe the gravitational waves directly. The challenge is that they are extremely weak. To make waves large enough to be detectable with any instrument we can imagine building on Earth, the most violent events in the universe are required: supernova explosions, the formation of black holes or the collisions of stars. Even so, the effects are tiny: The geometry changes so little that a distance of several kilometers changes by less than the diameter of a proton. To detect such changes requires enormous machines that bounce light back and forth over paths many kilometers long. Efforts to build these gravitational-wave interferometers are currently under way in the United States, Italy, Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Australia, Japan and other countries, whose governments have invested so far more than $300 million in the search to detect gravitational waves. But despite the enormous effort and expense, no waves have been seen.

Harry Collins's book offers an opportunity to understand whether experimental physics is really as simple as we were taught in high school. Naively, we talk about using a particle detector to "see" a particle, or the Wilson Microwave Anisotropy Probe to "see" the cosmological microwave background. But these are complex instruments, built and run by large groups of people. What is "seeing" when the image we are finally shown on the front page of a newspaper is the output of a computer program that is itself the outcome of a decades-long process involving large numbers of people and machines? This is the central question Collins is concerned with.

Like particle accelerators and dark-matter detectors, gravitational-wave observatories require collaborations of hundreds of scientists, working in many different universities spread across the globe. But even with huge investments and large teams of scientists, the experiments are hard to do. The signals being looked for are rare and must be distinguished from millions of spurious events. Often you cannot tell just from the raw data whether anything has been seen or not. Very likely the signature you are seeking will be, just by chance, mimicked by noise in your instrument. How do you decide when you have registered a rare signal often enough to be sure that you are seeing something besides the random effects of noise in your detector?

When the difficulty of the experiments is combined with the social dynamics of large teams, things get very far from high school science. To take just one question, raised by the historian of science Peter Galison: How does a large collaboration decide when an experiment is finished? Do they vote? That seems hardly good enough—scientific truth is not a matter of the view of the majority. But if consensus is sought, what about the few cautious holdouts who will always insist on waiting for more data before announcing a result? And should we worry that the group may be more likely to embrace an analysis of the data that agrees with what the theorists want than one that disagrees?

Indeed, what happens when a good scientist believes that he or she has made a discovery but fails to convince colleagues? The shadow in Gravity's Shadow is just such a story.

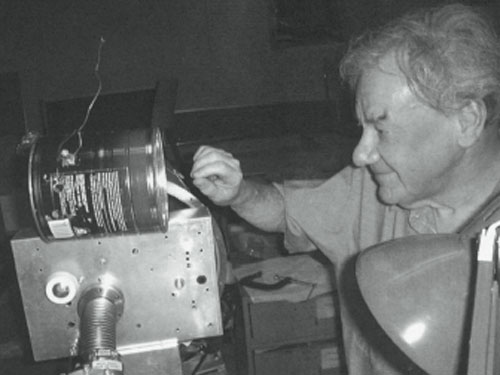

The pioneer of gravitational-wave science was an American experimentalist named Joe Weber, who announced in 1969 that he had detected gravitational waves—not with enormous machines, but with furniture-sized devices that he and a few students had built and operated in their lab. The problem was, when other physicists tried to replicate Weber's results, most of them couldn't. Even more unhappily, when they analyzed his experiments, they concluded that his electronics were too noisy to have seen what he claimed. The outcome, sensitively related by Collins in what is the emotional core of the book, was tragic. Had Weber been willing to accept the judgments of his colleagues, he would have ended his life loved and admired as the pioneering founder of a field of science. Instead, his insistence that he was the only one who could do the experiment right forced him to embrace a series of more and more unlikely and implausible hypotheses, which alienated him from those who had followed in his path.

Collins's book is long and full of detail, but it is an entirely rewarding read. Just like the physicists he studies, he has made the search for gravitational radiation his life's work. For three decades, he embedded himself in the community of gravitational-wave researchers, interviewing all the key scientists, visiting their labs, and attending many conferences, workshops and meetings. Funding agencies and scientists opened their files and archives to him. The resulting narrative is as provocative as it is convincing. There is a lot written by philosophers and others about how science is supposed to work. But this is the one of the very few books I've read that tries to help the reader understand what really goes on these days in the world of big science.

Not surprisingly, the answers to the question of how science works are not simple. One response is that scientists apply well-tested methods, which necessarily lead to an increase in truth; politics and sociology play minimal roles, for the processes by which scientists arrive at truth are foolproof enough to mitigate against the complexities of other human endeavors. At the other end of the spectrum is the relativist's belief that contemporary science is nothing but academic politics—to be comprehended as a sociological phenomenon that no more approaches truth than do the activities of other organized communities. In the early 1990s there was a very public argument between these two poles, which was dubbed the Science Wars.

Collins's book is an overdue antidote to both kinds of naiveté. He dubs himself a "methodological relativist," but he insists that this means only that as an observer of the processes by which scientists make decisions and come to agreement, he cannot himself try to reach his own views as to what is true or false in the science. The aim of his study is not to decide whether Weber or his critics were right. Rather, it is to understand the processes by which a community of scientists came, uncomfortably but almost unanimously, to the conclusion that its founding member was wrong.

The second half of Gravity's Shadow is about how the search for gravitational waves was taken up after Weber. With the consensus that Weber fooled himself came the realization that it would take huge machines, costing hundreds of millions of dollars, to actually see gravitational waves. Thus the search for these waves, which started as small science in one professor's laboratory, ends up as a paradigmatic example of big science. The present American detectors, which are part of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) project, have been built and are run by a process that seems more akin, in organizational style, to a big industrial project than to our romantic notions of what happens in an individual scientist's laboratory.

As Collins tells the story of how science by lone seeker became science by international committee, he provides us with the material to think hard about the meaning and cost of the transition. And these are questions we should be asking. No one believes that a large advertising agency or a Hollywood film studio can easily produce art with the lasting value that a single painter may achieve in his or her studio, even if people of equal talent are employed. Why do we believe that organizing scientists into groups and teams run by professional managers will easily result in discoveries of the same import as used to be made by heroic pioneers such as Galileo and Faraday?

From Gravity’s Shadow.

Indeed, the story Collins tells is very much about the conflict between science as done by individuals and science as done by modern large-scale organizations. And unfortunately, Weber is not the only tragic figure in the drama. Some of the key ideas and techniques that make the present detectors possible were invented by the Scottish physicist Ron Drever. But halfway through the development of LIGO, he was forced out of the collaboration because he refused to stop voicing his objections to the decisions of the project directors, who necessarily spent more time with schedules, budgets and reports than they could with equipment in the lab. Drever was convinced that the right path was to build incrementally, through the careful testing of larger and larger prototypes. Other scientists disagreed and insisted that the need to keep the project on time and within budget required them to freeze the design, even if everyone involved knew it was suboptimal.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of Collins's book is that he tells this part of the story in a way that makes the reader sympathize with all participants. This balance is the fruit of his many years of interaction with the scientists: He understands that the issue is not good and bad individuals but an inevitable conflict between different modes of organizing creative work.

One of the most fascinating parts of the story is what has happened since the conflict was resolved. After spending $300 million, LIGO is on schedule and is starting to report data. But the version presently being run, the initial LIGO, is not expected to be sensitive enough to ensure that it will detect gravitational waves. Given presently accepted estimates of the strengths and frequencies of events that cause the waves, there is a reasonable chance that it will see nothing.

There is an upgrade called Advanced LIGO that could make detection of gravitational waves more likely. It is not yet funded, and we can only hope that the U.S. Congress will have the vision to support it.

The reader is bound to ask, however, How was a decision reached to spend hundreds of millions of dollars of the public's money to build an experiment when it was understood that it might well see nothing? Part of the answer is that the scientists involved were able to assure the National Science Foundation (NSF) that the upgrade to Advanced LIGO, which was to be based on technologies then under development, would be able to increase sensitivity to the point that detection of gravitational waves would become likely. But the decision to go ahead before these technologies were ready and before Advanced LIGO had been funded certainly contained elements of risk both for the scientists and for the NSF.

Collins makes it clear that it is not his job to second-guess the science or the decisions of policymakers. We will know in a few years whether the risk paid off. But it is Collins's job to show us how scientists and decision makers invent the contexts, intellectual and organizational, within which decisions about science get made, and Gravity's Shadow does this better than any book I have ever read.

As Collins tells it, only part of the answer lies in the need to keep to schedules and budget. At least as influential was that the scientists leading the project feared repeating the embarrassment of Weber's false discovery. Weber's shadow thus appears to darken the whole enterprise. If you build too ambitiously, your experiment may not work, or you may not understand the data well enough to know whether you have seen anything. Better to be very careful and see nothing, but know for certain that you see nothing, than to risk announcing a false discovery. When one takes into account these kinds of risks, it becomes understandable how, within the LIGO collaboration, it came to seem more rational to first build a machine that had a low chance of achieving success.

Of course, even if the initial LIGO finds nothing, some science will have been done. One of the arguments made for the huge investment in LIGO, when there was already indirect evidence that gravitational waves exist, is that it might discover something completely unexpected: Perhaps the dark matter produces huge bursts of gravitational radiation, or perhaps there are unknown processes that produce more energy in gravity waves than light. It was argued that every time a new technology has opened an observational window, something surprising has been seen.

In the end, this is a book that raises important questions about big science without pretending to answer them. Is the present system really the best way that funds could be allocated and priorities set in science? There is certainly room to wonder whether, if it is not okay to invest heavily in theories that make no experimental predictions, there might also be something troubling about huge investments in experiments that are not sufficiently sensitive to ensure that they can discover anything. On the other hand, perhaps the path that the LIGO scientists chose is the only way the project could have been run. After all, if science cannot progress without risks being taken, then big scientific collaborations must be able to take big risks as well.

What is certain is that we cannot address these kinds of questions without a detailed understanding of how decisions are actually made within the large communities that make up contemporary science as well as within the government agencies that support scientists. Harry Collins has shown us in this book that it is possible to do the kind of careful, sensitive scholarship that makes mature reflection on such questions possible. This is a book that everyone who cares about the future of science should read.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.