This Article From Issue

January-February 2002

Volume 90, Number 1

DOI: 10.1511/2002.13.0

Racing the Antelope: What Animals Can Teach Us About Running and Life. Bernd Heinrich. xii + 292. HarperCollins, 2001. $23.

As a marathoner, I have long held that Homo sapiens is not evolutionarily adapted to run. Compared with just about any four-legged creature of similar size, we seem pathetic.

But in Racing the Antelope: What Animals Can Teach Us About Running and Life, Bernd Heinrich argues otherwise—convincingly. He has near-perfect credentials to make his case: A biologist by profession—indeed, the increasingly rare type who likes to look at whole animals—he has held the masters (40 and older) world record for an ultramarathon (100 kilometers) since 1981 (when it was a world record for anyone of any age). In this, his seventh book, he mixes his academic, athletic and verbal skills synergistically to explore endurance in creatures ranging from the hawk moth to himself.

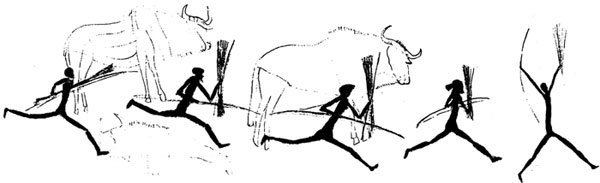

From Racing the Antelope.

Part autobiography, part natural history, part lab notebook of experiments with his own body, Racing the Antelope ranges from the author's formative years in World War II Germany and rural Maine, to the biology of how animals and human beings accomplish amazing feats of endurance, to training for and winning a race the very thought of which makes me cower. All of these facets of the book are interesting, but I was most fascinated with the possibility that Heinrich is right in maintaining that "We are all natural-born runners, although many of us forget this fact."

A two- or three-thousand-year-old pictograph in Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe, shows hunters running, the leader with his arms raised in the universal expression of running triumph. The Penobscot in Maine designated young men specifically as runners to chase down moose and deer. A variety of other Native Americans ran down everything from antelope to bison to black-tailed jackrabbits, and as recently as the 1950s Navajo still practiced running deer to exhaustion. These hunters used endurance to outlast prey that were capable of much greater speed, but only for short bursts.

Heinrich proposes that we evolved to our current form as endurance hunters. At first we may not have been able to catch and bring down any but the weakest prey. Nonetheless, the ability to cover large distances quickly helped us as scavengers to reach carcasses before competitors did. Over time we developed into highly effective hunters, able, perhaps, to outrun enough mastodons to push them to extinction.

Physiologically, Heinrich says, our bodies are exquisitely well adapted for the long run. Our flexible Achilles tendons, our arched feet, our strong big toes all add up to a running gait. We come, on average, with about an even distribution of fast- and slow-twitch muscle fibers—the former provide short bursts of power, and the latter support sustained activity. Yet through exercise we can recruit certain of those fast-twitch fibers for slow-twitch duties. Our lungs, blood and circulatory system supply crucial oxygen to those fibers for aerobic processing, allowing them to burn fat for energy—the long-term solution to fueling our motion.

Of equal importance to aerobic capacity in endurance exercise is the ability to get rid of the heat of metabolism. This is a limiting factor in many species, yet we do it extraordinarily well. Bipedalism, the author suggests, may in part be an adaptation to reduce solar input and increase exposure to convective cooling. Our ability to perspire, which provides evaporative cooling, is unparalleled (we have 3 million sweat glands) and works in tandem with a lack of body hair.

Heinrich also argues that we are psychologically adapted to endurance hunting and therefore running, since we can visualize far ahead and use our imagination to motivate ourselves.

Bernd Heinrich is a superb runner (not to mention writer and scientist), which suggests that his ancestors were as well. Me and mine? My results sheets suggest that it's a good thing I don't depend on running for dinner.—David Schoonmaker

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.