Regeneration on Tree Mountain

By Robert Chianese

Fusing artful beauty with functional utility could help heal the environment, and restore our humanness.

Fusing artful beauty with functional utility could help heal the environment, and restore our humanness.

DOI: 10.1511/2013.104.350

In previous issues I analyzed major works of Earth art that I found more aesthetic than ecologic. Now, I wrap up this series of columns by looking at examples of Earth art that are deliberately green—that actually help restore the Earth. Agnes Denes has been creating these kinds of works for decades.

Denes gained notice in the United States for Wheatfield—A Confrontation (1982), a two-acre field of grain she planted on an empty, four-acre lot right next to the World Trade Center towers. She cleaned the land, covered it with 200 truckloads of soil, and then hand planted seeds that reaped 1,000 pounds of wheat. Denes then shipped that wheat to 28 cities around the world as part of an art show about ending world hunger.

The “confrontation” of her project’s title refers to the challenge the wheat field posed to the financial capital of the world and its obsession with accumulating wealth rather than serving human needs. This is in-your-face Earth art pushing a comprehensive environmental agenda.

Denes is a visionary whose work, she proclaimed to me, cannot be fully characterized by the label “restoration Earth art.” I agree. She incorporates science, mathematics, and philosophical pronouncements into her work, which has both a conceptual basis and direct social and ecological effects through built-in public involvement. However, many of her projects do involve restoration and reclamation—components I find missing in so many examples of Earth art.

The health of the planet is in a precarious state and cries out for such restoration more than ever. Earth artists often use natural materials and forms just to dazzle us with their imaginative constructions. They may have to stretch themselves to embrace this more complicated phase of their movement, making art that emulates Earth processes, as Denes surely has.

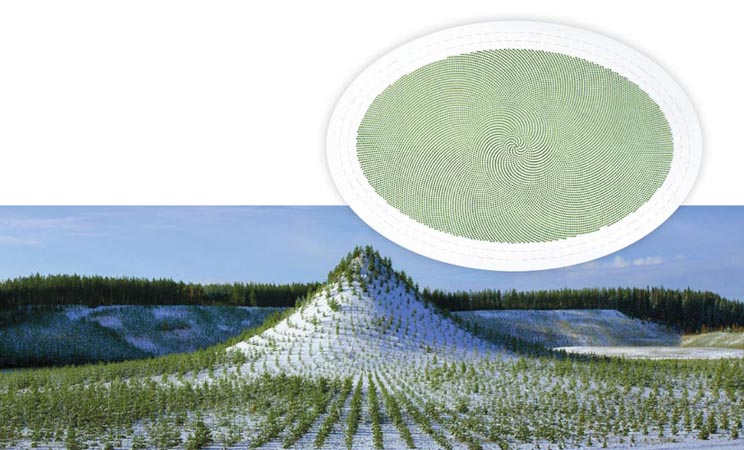

© Agnes Denes/Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects, New York

Her Tree Mountain—A Living Time Capsule (1996 to the present) brings together essentials of her Earth art on a scale that is hard to imagine. She had a mountain of soil piled into an elliptical cone over a gravel pit near Ylöjärvi, Finland; it measured 420 meters long, 270 meters wide, and 28 meters tall. She then had 11,000 people plant 11,000 trees in a golden section and “sunflower/pineapple” pattern around her mathematically designed mound; convinced the Finnish government to promise to preserve it for four centuries; and gave the tree planters and their heirs the right to pass on their living legacy of a tree for at least 20 generations. That is the time-capsule element of Tree Mountain. In her artist’s statement, Denes says:

The forest will be kept for the next 400 years, thereby creating the first manmade virgin forest. It will take that long for the environment to re-create itself. The 11,000 people who came to plant the trees received a certificate valid for four centuries that they can leave to their children as custodians of the trees. My forests are mathematical in order to combine the human intellect with the majesty of nature. I restore the land, rejuvenate it, and fill it with wonders of new human understanding.

Denes’s grand project required support of a multigovernmental agency—the United Nations—and the Finnish Ministry of the Environment. Works like this one force governments, foundations, benefactors, and the public to reconceive the role of art in our lives. Talk about civic engagement!

I am not proposing that all Earth art must produce a growing, living, green thing. Other famous works that I have examined in this series—such as Robert Smithson’s salt-encrusted jetty, Andy Goldsworthy’s curvy stone wall, or Michael Heizer’s massive rock—can bring our desensitized relationship to the land to fuller awareness. We need that, but maybe less so as the fate of the Earth becomes all too apparent. Earth art might commit itself to performing some of the actual remediation work, where ecological function complements aesthetic design.

Denes almost embraces a radical belief that, in our calamitous, postmodern world, art must be appropriately “malignant,” never “benign.” Quoting her again: “Beauty is the sure bearer of weakness, and usefulness is a killer. Art should be above all that, it should nauseate, disturb, arouse, and so on.”

But then, she reverses herself: “Okay, why not, but I feel that beauty can also be so brilliant and breathtaking that it disturbs. And art can be useful in an ailing world and natural, not artificial and still be great art.”

Denes offers a profound corrective, a new aesthetic for our time: a beauty that disturbs in its brilliance, and a natural usefulness that can help heal an ailing world. Tree Mountain does that. Its scale and its green reality—a new vast forest—can awe us with overwhelming beauty; this used to be called the “sublime.” The use of the forest not for products but in its natural state defines it as a healing resource for those who wander through it, reflect on it, sense it, watch it grow and evolve, and thereby receive a sort of convalescence.

Because of its overwhelming presence, Denes’s work might suggest that restoration Earth art needs to play out its drama on a grand stage. But it can also perform effectively on a more accessible scale.

A small art park near my home in Ventura, California, incorporates an elegantly humble work titled Pepper Tree Garden (2008), which passively cleans runoff water by channeling it through a rocky trough planted with native filtering plants. Water then swirls around a large shallow basin, its sides lining the drain with wire-secured limestone wedges. These eight patterned gabions of limestone deacidify the water before it sets out on its underground return, via a drain system, to the ocean miles away. Water-cleansing sections of landscaping like this are known as bioswales. Signage in the park explains that Pepper Tree Garden sits at the end of natural hillside drainage and over a water-pumping station for hillside residences. It therefore extends and complements natural water flow in the area.

City-sponsored eco-artist Kathryn Miller, in collaboration with Andreas Hessing, chose pieces of limestone that hold fish fossils for the basin structure, perhaps to connect the ancient fish with the modern ocean fish the cleansed water helps maintain. This imaginative blending of paleontology and biochemistry yields effective and pleasing results. Local botany and basic principles of hydrology are all the rest of the science required to make the bioswale work.

The utility of Pepper Tree Garden as a natural rainwater purifier is obvious. Its beauty stems from its simplicity, plainness, and directness—standard attributes of good style in many endeavors. We’re back to “form follows function.” Such a traditional aesthetic connects beauty with utility: At appropriate scale, Pepper Tree Garden forms the terminus of the natural slope that contours the park, drawing us and everything else to it. The white octagon, with its lollipop shape and decorative fossil stonework, contrasts with the green growing things around it. Is it an umbrella for catching rain? The built and the natural coexist and complement each other, with beneficial environmental effects.

Such Earth art points the way to using art, environmental science, and basic engineering for ingenious, low-cost projects. The future of restorative Earth art may lie with both modest works like Pepper Tree Garden and the grand eco-artistry of renowned figures such as Denes. Fusing science and art can stimulate both to help green the planet in very earthy ways.

Restorative Earth artworks may more broadly revive that older aesthetic wherein beauty and utility serve each other as forms of healing. Denes finally steps forward and champions such an aesthetic, even though postmodernists might find it quaint. Pieces such as Tree Mountain and Pepper Tree Garden may wind up redefining both art and our relationship to the environment—recovering the latter from neglect and damage, while replenishing our humanness, diminished by our modern disconnections from the natural world.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.