This Article From Issue

September-October 2006

Volume 94, Number 5

Page 469

DOI: 10.1511/2006.61.469

Doctor Franklin's Medicine. Stanley Finger. xiv + 379 pp. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006. $39.95.

Few personalities swept a more luminous arc through 18th-century America than did Benjamin Franklin. An autodidact, polymath, patriot and successful businessman, he was wealthy enough at the age of 42 to retire from commerce and devote the rest of life to philanthropy, diplomacy and science. Among many achievements, he may have been the first to have the powerful insight that the various manifestations of electricity are a single phenomenon best understood as a kind of fluid.

Franklin's celebrity was due to his formidable intelligence, unparalleled energy and admirable assiduity, and also to circumstance: He owned a printing press, and his literary alter ego, Poor Richard, had something to say about almost everything of interest to a broad, Colonial audience.

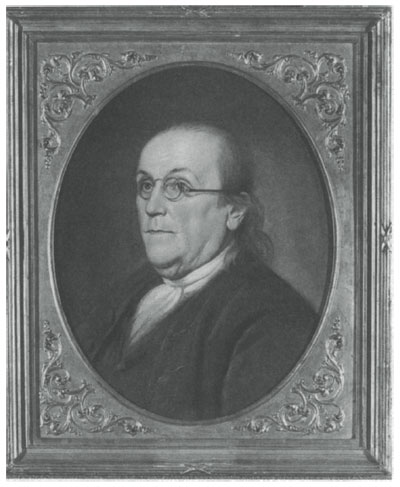

From Doctor Franklin's Medicine.

Franklin also actively sought fame, and some of his renown was self-created: He dissimulated humility while inwardly belittling it. "I cannot boast of much Success in acquiring the Reality of this Virtue, but I had a good deal with regard to the Appearance of it," he wrote candidly in his Autobiography. He smoothly ingratiated himself with many of the best thinkers and doers of his time, without seeming to try, but trying all the while, especially in his younger years. To gain the attention or favor of someone important, he suggested, one should ask to borrow a book from that person's library—a marvelously disingenuous method of flattering even the most wary. He also counseled that older mistresses are to be preferred because they are so much more grateful.

In short, Franklin's oversized personality was ambiguous and complex.

In Doctor Franklin's Medicine, eminent neuroscientist and medical historian Stanley Finger admirably lays out Franklin's association with the medical advances of his time. The book's introduction opens with an account of an event that is almost cinematic—the uncloaking of Mesmerism. In what was presumably the first use of the blind protocol in modern times, Franklin and a committee of other notables conducted a test of Franz Anton Mesmer's theory that an invisible fluid, animal magnetism, permeated the universe and could be directed into objects, which could then be used to cure illness. A blindfolded boy, asked to identify which of several trees had been "magnetized" by one of Mesmer's followers, was unable to do so correctly.

The remainder of the book is organized chronologically and by scientific discipline. Finger describes Franklin's contributions to the emerging recognition of the health benefits of exercise and fresh air, the promotion of inoculation against smallpox, the establishment in America of the first hospital and then the first medical school, the formation of scientific and medical societies, the understanding of airborne contagion and lead poisoning, the resolution of the struggle between theorists and pragmatists in medicine, and advocacy for the therapeutic role of music. The last chapters deal with Franklin's more intimate connection to medical conditions from which he personally suffered: presbyopia, gout, a chronic skin disease (presumably psoriasis) and bladder stones. We see Franklin develop through his own experience a sobering appreciation of the limits of medicine.

As Finger conducts this fascinating tour of medical history, he enlivens the narrative with information that is often useful and always interesting. What does the word "inoculation" have to do with the eye? What is "small" about smallpox? Why is gout so named? Numerous other fascinating anecdotes and little histories demonstrate a broad scholarship and an eclectic passion for knowledge. The book's extensive endnotes facilitate entry into both the primary literature of Franklin studies and the intellectual history of his time.

Doctor Franklin's Medicine is a valuable and entertaining work. However, Finger wisely concedes in his preface that this is not a definitive book on Franklin's contributions to medicine; he hopes others will undertake that project. I hope so too.

Franklin's dazzling career has led to the creation of an apparently solid edifice, which no doubt conceals some element of myth, and my only quibble with the book's assessment of Franklin's contributions to medicine is that it may not be critical enough. Finger does not dwell on the complexity of his subject's character and generally takes the Franklin mythology at face value. For example, did Franklin independently invent (or reinvent) the blind protocol that is so important to modern scientific method? Or was the protocol the contribution of Antoine Lavoisier, the even more brilliant father of modern chemistry, who served with Franklin on the committee that helped to debunk Mesmerism? The latter may be true, but as Finger points out, Franklin's signature appears above those of his colleagues on the final report. One would have to dig deep to find the truth.

Franklin the scientist deserves further scholarly scrutiny, not to diminish him but to reveal the man as he was. Within the past decade or so, a number of authors have begun to demythologize that other meteor of the 18th-century American firmament, Thomas Jefferson. I hope someone will follow Finger's advice and untangle the multiple strands of Franklin's contributions to the development of scientific medicine. Was he an innovator or a popularizer? A scientist or a gifted enthusiast? I expect he was some of each.

Franklin's brilliance is unquestioned, but how much of it is reflected light?

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.