Learning from Rural Disaster Recovery

By Kristen Fontana

After two record floods swept through Robeson County, NC, in 2016 and 2018, government assistance fell far short of residents’ needs. How can coastal communities prepare for the increasing risk of rising waters?

December 19, 2023

Macroscope Anthropology Economics Environment Ethics Policy Sociology Climatology Social Science

More than 150 hand-written index cards and sticky notes were strewn all over the floor as the TV blared the recent COVID-19 updates. This scene is what research looked like for Tira Beckham, a PhD student in forestry and environmental resources at North Carolina State University (NCSU), in 2020. Sifting through more than 600 pages of interview transcripts, Beckham was conducting a qualitative analysis to study disaster recovery governance in Robeson County, NC, after Hurricanes Matthew (2016) and Florence (2018).

The tannin-rich Lumber River snakes its way along the southeastern border of Robeson County, with its tributaries branching throughout, forming biodiverse cypress swamps and lowland farms and forests. Interstates 95 and 74 intersect in the middle, near the county seat of Lumberton, which harbors a historic downtown and some strip malls. In early American history, white settlers avoided this swampy area, and so it became a haven for runaway and freed slaves and the Lumbee tribe. Today, Robeson County is one of the most diverse counties in the nation, and it has North Carolina's lowest median household income. From December 3, 2019, through September 1, 2020, a team led by Bethany Cutts at NCSU and David Shane Lowry of Biola University in California interviewed 80 Robeson County residents about their experiences with Hurricanes Matthew and Florence through a program called the Project to Building Resilience by Innovating through Diverse Group Engagement (Project BRIDGE). Beckham began to compile, organize, and analyze the interviews soon after.

State Highway Patrol

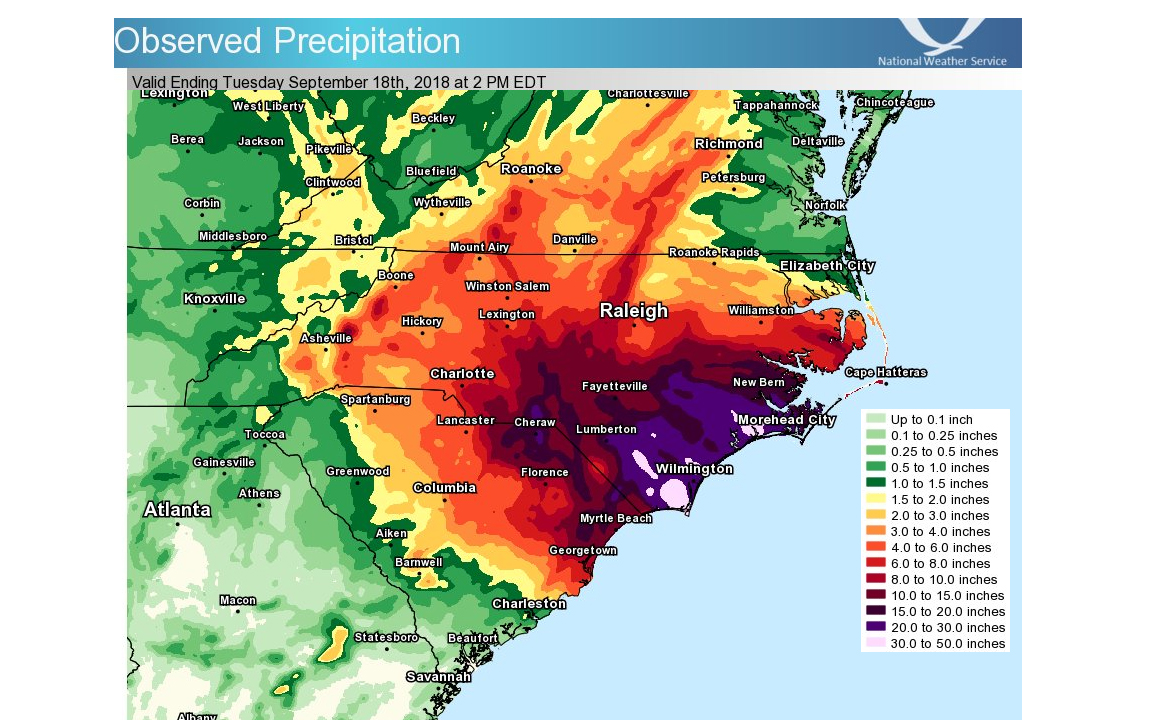

The catastrophic damages caused by Hurricanes Matthew and Florence altered the sociopolitical landscape of North Carolina, shifting priorities to climate-related recovery and resilience, as exemplified through Governor Roy Cooper’s 2018 Executive Order to declare the state’s commitment to fight climate change. Both hurricanes caused record flooding to North Carolina’s rivers. The Lumber River experienced a record high crest during Matthew that was then surpassed by Florence, closing I-95 for weeks.

These extreme weather events highlighted the challenges that rural and socially vulnerable communities, such as Robeson County, face when disaster hits. Because Robeson County is estimated to have a 1 percent chance of flooding in any given year (adding up to a 26-percent chance of flooding over a 30-year period), the community’s lack of resources means that its residents are at a significant disadvantage when it comes to extreme weather events and post-disaster recovery.

National Weather Service

After natural disasters, residents often rely on federal assistance for social and economic recovery. But for Robeson County, as well as other poverty-stricken areas hit by such storms, that path was not an option. “Especially in these rural, low income, small towns, community leadership is more important than government leadership.” Beckham says. “These residents depend on their community leaders because federal assistance and governments have failed them over the years.”

“These hurricanes are supposed to happen once every 100 years, but instead are happening much more frequently, and we are becoming unprepared,” explains Beckham. Inland flooding from Hurricanes Matthew and Florence inflicted severe social, economic, and agricultural disruptions throughout the county. For example, during Hurricane Florence, nearly two million gallons of sewage spilled in Lumberton and the town of St. Pauls, contaminating Big Marsh Swamp and the Lumber River. Many residents were left stranded as severe flooding damaged more than 500 structures in the county.

National Weather Service

As Beckham and her team reported in the October 2023 issue of International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, when disaster strikes, residents of Robeson County rely more on community leaders rather than their government for support. In discussing hurricane experiences, one Robeson County community activist shared that she had to post a call for help on Facebook, just for a county commissioner to come and hand out toothbrushes. Such minimal efforts from the county government were echoed by another interviewee who shared that food brought by the government had no use without the means to prepare it because of widespread power outages. Beckham and her colleagues’ analysis highlights the shortcomings of the county government’s hurricane response and emphasizes the important role of local leaders in providing effective disaster recovery support.

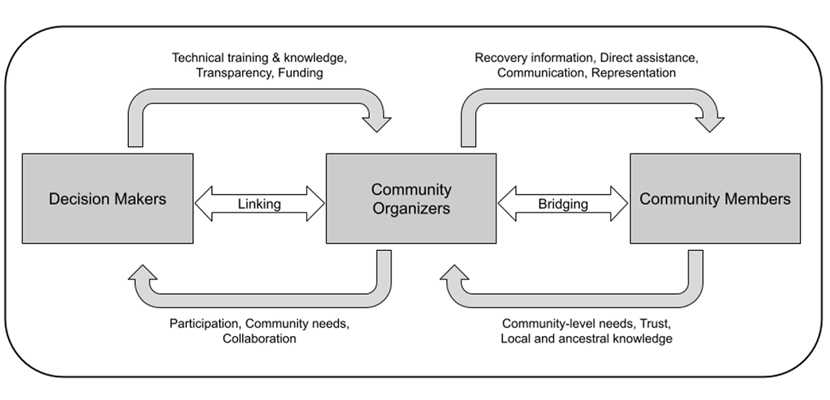

“Churches, in particular, play a huge role in the way that rural low income communities recover from disasters,” Beckham says. The study found that these community leaders not only have the trust of the residents, but also the commitment and determination to help the region recover from natural disasters. Community-level leadership, the researchers say, allows for two-way communication when developing effective solutions to support recovery efforts and increase resilience. Conventional leadership, on the other hand, offered a top-down approach that didn’t incorporate the local expertise of community organizers and thus perpetuated inequities. Beckham and her team found that by incorporating community leadership into the decision-making process, these low-resource communities can develop a sense of empowerment and autonomy over the disaster-recovery policies pursued in their region.

From the Project BRIDGE interviews, a series of mini-documentaries were developed to inform disaster recovery and planning decisions in Robeson County. Through sampling and participant recommendations, Beckham selected a subset of 30 interviews with disaster-recovery leaders who were self-identified or participant-recommended. Coined the BRIDGE Builder dataset, this subset consisted of county and city governments, nongovernmental organizations, religious entities, local businesses, educational institutions, and others from six cities across the county.

Image from Beckham et al., International Journey of Disaster Risk Reduction 96:103942.

Using qualitative analysis software, along with her handwritten index cards, Beckham developed a codebook that organized the Robeson County disaster recovery system into four emergent themes: actions, relationships, recognition, and resources. With this codebook, the research team developed a clear understanding of the current disaster recovery system in Robeson County, where there is room for improvement, and what barriers impede effective recovery efforts. Increased communication, transparency, efficacy, and efficiency were identified as desirable behaviors and actions Robeson County residents would like to see from their governmental leaders. Participants identified opportunities for cooperation and reciprocity through developing and maintaining relationships of trust between community members and decision-makers. Areas for improvement in Robeson County’s disaster recovery efforts also included better recognition for low-income and communities of color, who feel that their needs are not being adequately addressed in decision-making. All participants acknowledged the need for additional financial assistance to support local recovery efforts and the creation of community-level resilience and recovery planning efforts. To improve resources, community organizers identified the need for technical training and community climate recovery education. Such findings can inform improvement of disaster recovery in other rural areas, which face many of these same issues.

Disaster recovery governance can be complex, especially in socially vulnerable regions such as Robeson County. Beckham and her colleagues found that active participation of rural community leaders promotes recovery efforts that address the direct needs of the residents and fosters community strength and autonomy. Beckham hopes that findings from this secondary analysis will encourage decision-makers to work collaboratively with the community to build resilience for the next storm.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.