This Article From Issue

January-February 2008

Volume 96, Number 1

Page 64

DOI: 10.1511/2008.69.64

Arsenals of Folly: The Making of the Nuclear Arms Race. Richard Rhodes. xii + 386 pp. Alfred A. Knopf, 2007. $28.95.

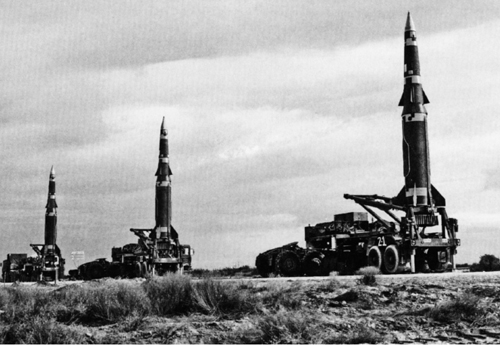

By early 1985, one year before the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in Ukraine, the United States, the Soviet Union and a few other states had together amassed 50,000 nuclear bombs and warheads. These devices threatened destruction 1.5 million times greater than the atomic bombing of Hiroshima 40 years earlier. Future generations of historians will struggle to explain why the leading Cold War states devoted so much treasure to so many of these horrible weapons.

From Arsenals of Folly.

In Arsenals of Folly, a passionate and sometimes eloquent new book analyzing the nuclear arms race, Richard Rhodes focuses on politics, particularly the politics of Soviet-American relations. He begins and ends by blaming American secrecy, aggression and insensitivity. "That arms race," Rhodes writes, "began with the Anglo-American program itself—the Manhattan Project—because the United States and Britain had chosen not to share knowledge of the secret program . . . with the Soviet Union even though it was an ally in the fight against Nazi Germany." Rhodes approvingly quotes Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who, after discussing the possible elimination of nuclear weapons with President Ronald Reagan in 1986, concluded that the Americans

have not abandoned the quest for superiority. That is why they did not have enough character, responsibility or political decisiveness to step over that threshold.

It seems to me that America has yet to make up its mind.

Devoting much of his text to Gorbachev's biography, Rhodes makes a convincing case for the last Soviet General Secretary's seriousness about replacing the nuclear arms race with a commitment to "common security." Gorbachev recognized that the construction of larger and more destructive nuclear arsenals only contributed to the bankruptcy and sclerosis of the Soviet Union. To reform the system—to create a more open, vibrant and effective socialist society—he needed to redistribute resources and talent to address civilian needs. Gorbachev also wanted to draw on scientific and economic cooperation with his West European neighbors rather than engage in military conflict with them. For all of these reasons, early in his tenure as general secretary he became a sincere advocate of seriously reducing, and perhaps eliminating, nuclear arsenals. Rhodes quotes a public letter from Gorbachev to Reagan, released in January 1986, in which Gorbachev proposed "a concrete program, calculated for a precisely determined period of time, for the complete liquidation of nuclear weapons throughout the world . . . within the next fifteen years, before the end of the present century."

Rhodes shows that the Reagan administration, like every American administration after the Second World War, failed to embrace bold measures for nuclear disarmament. Reagan personally favored the elimination of these weapons, but he continued to advocate a policy of American military superiority. He also refused to compromise his vision of a space-based nuclear shield—the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI). Rhodes repeats the conventional criticism of SDI:

Strategic defense was a dream, a fantasy, an uninformed winner-take-all bet that American technology could make miracles happen if only a sufficiently committed leader stepped forward to offer support and run interference. It was a fond wish. . . .

And if wishes were horses, beggars would ride.

Reagan was surely naive, but so is Rhodes in many of his historical assessments. Throughout the book he blames the United States disproportionately for Cold War tensions and the spiraling of the nuclear arms race. Many other authors have pointed to missed American opportunities for negotiation and disarmament, but the Soviet Union and other international actors—particularly China and France—are noticeably passive in Rhodes's narrative. They all seem to follow the United States. This U.S.-centered approach neglects the extensive scholarship published in the past decade that documents Soviet aggression, especially in the 1960s and 1970s. Soviet military maneuvers and interventions, according to this impressive body of research, contributed to strategic insecurity, nuclear tensions and American overreactions. Chinese and French efforts to escape superpower dominance of the international system also furthered Soviet and American insecurities.

In a history of the arms race that fills more than 300 pages of text, Rhodes devotes less than two pages to the Cuban Missile Crisis. He depicts Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, and the Soviet leadership as a whole, as defensive in their efforts to redress the strategic imbalance in nuclear-delivery vehicles. Although there is some truth to this assessment, it fails to take into account the enthusiasm, the belligerence and even the utopianism that accompanied Khrushchev's rational, but also reckless, decision to station nuclear weapons on an island so far from traditional areas of Soviet interest and so close to the United States. Washington's successful efforts to force the removal of the Soviet missiles surely humiliated Khrushchev, as Rhodes writes, but the experience also fueled American anxieties about Soviet and Cuban aggression, especially outside of Europe. Two years later, when President Lyndon Johnson confronted a series of difficult decisions surrounding the future of South Vietnam, he believed he had to "stand strong" in Southeast Asia, as John Kennedy had in Cuba, for both political and strategic reasons. American belligerence had its internal sources, but it was also a reaction—a reasonable one at the time—to Soviet moves.

The same could be said of the U.S. stance in the 1970s, when Moscow participated in a string of military interventions in Angola, Ethiopia and Afghanistan, among other places. Rhodes savages Richard Perle and other people he refers to as "conservatives"—including some in the Democratic Party—for exaggerating the Soviet threat. From a post-Cold War perspective, this argument is persuasive. It does not, however, account for the serious and legitimate anxieties that American policy makers felt at the time. In the aftermath of the fall of Saigon and the Soviet nuclear buildup of the 1970s—including greatly expanded capabilities for delivering warheads between continents—it reasonably appeared to some observers that Moscow was on the march. Hawkish conservatives such as Perle were not the only people who called for a military response to Soviet aggression in the 1970s. Even President Jimmy Carter, a skeptic of the value of nuclear weapons and an advocate of détente, believed that Moscow's interventions required a strong American response. Reacting to new Soviet rocket deployments in Eastern Europe, Carter authorized the placement of American intermediate-range, nuclear-armed missiles—the Cruise and Pershing systems—on the western half of the continent. As in other decades, the American nuclear buildup of the 1970s and 1980s was deeply influenced by Soviet actions. Rhodes distorts our understanding of the period in his polemical attack on conservative (or neoconservative) policy makers.

Arsenals of Folly is filled with the kind of compelling, emotional descriptions of nuclear events that readers are accustomed to finding in Rhodes's many distinguished books. His account of the 1986 Chernobyl disaster in the opening chapter should be required reading for all those who seek to understand both the risks of nuclear power and the long-term consequences of poor oversight. The passion, the clarity and the attention to telling detail that Rhodes brings to Chernobyl is the greatest strength of this book and of his body of writing as a whole.

Political and strategic analysis, however, is not Rhodes's strength. He depicts the arms race as a failure of political will. Gorbachev is his hero because he appears to make the personal commitment to nuclear disarmament that his predecessors and counterparts rejected. This historical assessment is, in the end, too simplistic: Weak leaders (for example, Truman, Eisenhower, Johnson and Brezhnev) made the arms race. Strong leaders (especially Gorbachev) worked to unmake it.

Political will and leadership surely mattered, but they were not dominant. The nuclear arms race was a competition that neither side wanted but neither managed to avoid. It reflected the profound insecurities of the United States and the Soviet Union after the Second World War, and their inclination to expect the worst of their adversaries. This was a classic "security dilemma," where each state built more nuclear weapons in self-defense, but each act of self-defense contributed to the adversary's insecurity and inclination to deploy more weapons. Uncertainty and misperception, as much as personality, drove the Cold War. These factors explain the policy consistency across decades and administrations.

The reason that the United States, the Soviet Union and a few other states had a total of 50,000 nuclear warheads in 1985 is that they saw no better alternative in what they took to be an insecure and threatening world. Rhodes captures the tragedy of this circumstance. A study of the causes of the arms race, and of its endurance, awaits another book.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.