This Article From Issue

March-April 2003

Volume 91, Number 2

DOI: 10.1511/2003.12.0

Love at Goon Park: Harry Harlow and the Science of Affection. Deborah Blum. xvi + 336 pp. Perseus Publishing, 2002. $26.

From the moment we are born to the end of life, we yearn for enfolding arms to comfort us. We embrace friends and loved ones in greeting and farewell, in times of joy and in times of sorrow. After any disaster, whether an earthquake or 9/11, what do strangers do? Weep and cling to one another as if to a life raft. Touch is the currency of reassurance, conversation, affection, understanding and love.

Americans, however, have resisted acknowledging the power and importance of contact comfort. A need for touch? Us? We are independent, logical, rational; apart from a few loony Californians, we don't need that "touchy-feely" stuff. Indeed, as cross-cultural studies have shown, we are an undertouching society: The groups most in need of touch—infants, children, the aged and the sick—are often those most deprived of it.

From Love at Goon Park.

Only in the past half century have American scientists and physicians started to understand what mothers in many cultures (Mayan, Italian and Japanese, for example) have known for millennia: that touching is as important to health and well-being as vitamin C. As Deborah Blum shows in her superb biography, Love at Goon Park, it was Harry Harlow who opened American eyes to the importance of human affection. (The book's title refers to Harlow's laboratory at the University of Wisconsin, which was nicknamed Goon Park because the address was 600 N. Park, and a handwritten "600 N." could be misread as GOON).

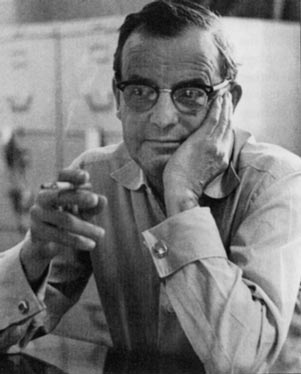

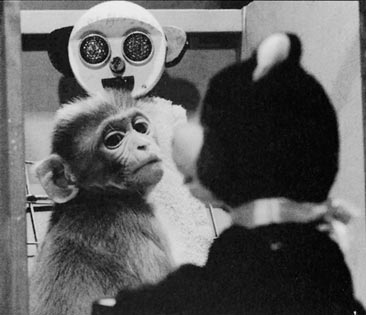

I interviewed Harlow for Psychology Today magazine in 1972, when I was a newly minted Ph.D. and he was already world-famous for research in which he raised baby monkeys with a "cloth mother" (a chicken-wire torso covered in soft terry cloth) or a food-dispensing "wire mother" (a chicken-wire frame with a milk bottle at the top). His photos of the infant monkeys, clinging for dear life to their lifeless but cuddly cloth mothers, were haunting and horrifying. Yet his work showed unequivocally that these babies—and presumably all primate babies, including human ones—needed "contact comfort" and cuddling to become attached to their mothers, thrive physically and have normal relationships; food was not enough. In those days, that was big news.

From Love at Goon Park.

I was pleased to reencounter Harlow, from a distance of decades, through Blum's book on the man and his work. (And I was pleased to find that Blum included parts of my interview in her book, along with comments I made to one of her researchers.) Although he was best known for his "wire-and-cloth mother" studies, Harlow was a giant in 20th-century experimental psychology, and a biography is more than warranted by his contributions to science and his place in the history of science. Like me, Blum was fascinated by his lively but troubled personality and his important but often cruel research. In my conversation with Harlow we wrangled about the ethics of his research—for example, the brutality, in one project, of separating infant monkeys from their mothers and keeping them in terrified isolation—and about his provocatively sexist remarks. "If you don't believe that God created women to be mothers and essentially nothing else," he said to me, "let me prove it to you." The proof consisted of a description of sex differences in monkey behavior, and then he finished triumphantly with the one sex difference he was sure of: "Man is the only animal capable of speaking, and woman is the only animal incapable of not speaking."

This was vintage Harry Harlow, unapologetically inflammatory before the term "political correctness" had been coined. He delighted in baiting me, a young woman coming of professional age during a rebirth of feminism; yet it seemed to me, even then, that he did so in a spirit of intellectual playfulness and provocation rather than meanness. Indeed, Blum shows that Harlow's sexist remarks and jokes seemed to be intended to rile people up and tease them rather than to be a reflection of some truly felt misogyny. In practice, where it counted, his male and female students received equal treatment—that is, he was equally demanding of everyone. He liked strong, independent female students and supported their careers.

Blum feels the same ambivalence about her subject that I did. Was he someone one could "like"? "Easy question, tricky answer," she says in her preface:

He makes me laugh, even secondhand. He makes me think about friendship and parenthood and partnership in ways that I never had before. He still seems to me an edgy companion. And he seems wholly real. So, like Harry, the answer is complicated. Sometimes I do like him, sometimes not at all. In the end—it's the both that makes him such a terrific subject for a biography—exasperating, sometimes, enchanting other times, never boring. And his weaknesses give a curious strength to his work—he was bitterly honest, sometimes to his own detriment. He was willing to take his personal problems—loneliness and isolation and depression, even—and use them in his research.

This paragraph illustrates why this book is so good both as a contribution to the history of science and as a biography. Blum avoids the twin temptations of hagiography and character assassination. She gives us the strengths and weaknesses of Harlow's character and work, placing both in the context of what was happening in psychology and in the larger culture. Harlow made many discoveries that were pioneering, indeed heretical, at the time: for example, that monkeys use tools, solve problems, and learn and explore because they are curious or interested in something, not just to get food or other rewards. But his greatest contribution was his demonstration of the power of "mother love" and the necessity of contact comfort—and the devastation that ensues when an infant is untouched, unloved, neglected.

Was Harlow the first to demonstrate this need? No, both René Spitz and John Bowlby had, much earlier, shown how infants raised in orphanages sickened and failed to thrive if they were fed but never cuddled. Was experimenting with monkeys, by raising them in isolation with only wire or cloth "mothers" and causing them anguish that no observer could fail to see, essential to make the same point? Probably not. I feel about Harlow's studies as I did about Stanley Milgram's famous studies of obedience to authority, in which large numbers of people inflicted what they believed to be serious pain on another person because the experimenter told them to. Did we not have enough examples from history to confirm that, as C. P. Snow observed, "more hideous crimes have been committed in the name of obedience . . . than in the name of rebellion"? What Harlow and Milgram were able to do, however, was to make the case for their findings dramatic, compelling and scientifically incontrovertible. Their evidence was based not on anecdote, however persuasive the story, but on solid, empirical, replicated data. As Blum shows, that's what it took to begin to undermine a scientific worldview in which the need for touch and cuddling—physical expressions of mother love—was ignored.

Love at Goon Park is utterly devoid of the psychobabble and post-hoc psychodynamic reasoning that are the hallmarks of most journalists and many historians who attempt psychological biographies. Blum has written an invaluable story for all students of psychological science, for she shows how science is really done and how its findings are used and often misused. Scientific discoveries are a result not only of a bloodless progression from hypothesis to experiment to refinements, but also of the investigator's personality and passions, and of lucky accidents—who happened to be where, when; who was lucky enough to work with whom. Science also depends on knowing when to follow your hunches and when to change direction, and on knowing the difference between an obstacle in your path and a dead end. Blum brings all of these elements of scientific discovery to life in Harlow's story.

For example, she shows that in spite of Harlow's difficult personality, his drinking problems and his bouts of severe depression, he was the consummate scientist and mentor, supporting his students through good ideas and failures. His graduate student Leonard Rosenblum had been working on an experiment that involved building a large, complicated maze that would allow him to measure the social and intellectual behavior of monkeys. Rosenblum worked for months with no results, and one day Harlow came by and said, "Rosenblum, take a sledgehammer to that thing and get rid of it. . . . You've got to know when to quit." Rosenblum was shocked but realized Harlow was right. "If you cling to errors, you never learn the right way. It was a very difficult lesson," Rosenblum told Blum. "I was embarrassed and ashamed. But he didn't see it that way." Rosenblum went on to devise a crucial variation of Harlow's paradigm, raising infant monkeys with the chance to play regularly with their age mates. These babies grew up to be as socially healthy as those raised with real mothers.

One annoying problem for scholars who read this book is the dreadful compilation of notes at the back, which are not even keyed to pages, let alone paragraphs, making it often impossible to track a source for some particular assertion. A more general problem in the text is Blum's tendency to imply that the "bad old days" of narrow-minded, misguided psychological advice are past—such as advice based on the radical behaviorism of John Watson and his school. We understand, we say, so much more about the importance of bonding, contact, attachment! Yes, we do, but we are no less vulnerable to today's social pressures and cultural values, or to the misuse of science on behalf of vested interests—especially the many vested emotional, political and economic interests involved in contemporary child-rearing practices and notions of "correct" mothering.

In Blum's hands, Harry Harlow emerges, for all his flaws, as the kind of scientist who is an endangered species: willing to speak his mind and speak it clearly, free of cant or jargon, no matter whom his remarks offended; willing to follow his data where it took him, even against the tides of popular opinion. He would never get tenure today.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.