This Article From Issue

January-February 2007

Volume 95, Number 1

Page 77

DOI: 10.1511/2007.63.77

Jane Goodall: The Woman Who Redefined Man. Dale Peterson. xii + 740 pp. Houghton Mifflin, 2006. $35.

Dale Peterson has given us a beautiful book—a flowing, detailed biography of Jane Goodall that clearly explains her insights and why they created a watershed in the scientific understanding of animals. His portrayal of her is highly complimentary, even worshipful; but then, Goodall deserves the praise. Peterson has achieved the tour de force of conveying Goodall's charisma while explaining the significance of her science—and indeed, why neither would exist without the other.

"Dale Peterson knows me better than I know myself," Goodall says. Peterson coauthored a book with her and edited the two volumes of her letters. With this biography, readers will know her too—and many will wish for even more.

Peterson proceeds at a leisurely pace, going into great detail about Goodall's childhood and early career. She doesn't sight her first wild chimpanzee until almost 200 pages into the text. Not until page 546 do we reach the crisis in research at the Gombe Stream Reserve, the night in May 1975 when "forty intruders, dressed in gray military fatigues and carrying rope, hand grenades, and AK-47s" kidnapped four American students and carried them off to the guerrilla camp of Laurent Kabila, future prime minister of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Peterson, however, gives short shrift to Goodall's career since her decision in 1985 to turn from research to activism, compressing the past two decades into a mere 80 pages.

The book opens with a description of Goodall giving a lecture, her blond ponytail now silver, her figure spare and upright, her voice limpid as clear water, her phrases focused like the sharpest binoculars. Afterward scientists and laypeople line up with her books to get an autograph—and to tell her what she means to them. "A young girl with braces on her teeth: ‘When I was in sixth grade, I had to do a research project. I did it on chimpanzees. And you!'" Another listener says simply, "May the universe bless your work."

Then we meet the child Jane, born Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall on April 3, 1934. She grew up in an unremarkable middle-class home in unromantic Bournemouth, in a household of strong women. Her racing-driver father was away much of the time, then joined the military and was posted overseas, eventually writing to request a divorce. The small girl dreamed of working with animals in Africa like her hero, Doctor Dolittle. Only a few teachers, however, and perhaps only with hindsight, recognized her extraordinary intelligence and powers of concentration.

Having no money for university, she trained as a secretary—and then grew to be an astoundingly accomplished flirt, to judge by the number of her beaux and even fiancés. (But none of them seems to have made as permanent an impression as her dog, Rusty.) Here Peterson perhaps underplays how much the culture of the 1950s directed young women's ambitions toward marriage. Goodall's giddy youth in part shows how successful she was at what was then the expected career path.

In 1955, Goodall was invited to Kenya by a school friend. She eventually saved enough money for the voyage and arrived in Nairobi in 1957, on her twenty-third birthday. There she met archaeologist Louis Leakey and quickly won him over, along with many others. One letter home exclaims, "What the devil am I to do with all these middle aged married men? They hang in multitudinous garlands from every limb and neck I've got." With difficulty she persuaded Leakey to confine his role to paternal kindness. Eventually he offered her the chance to study wild chimpanzees at the Gombe Stream Reserve on the shores of Lake Tanganyika (which later became part of Tanzania).

Here we begin to see the importance of chance in Goodall's life. Her accomplishments now seem inevitable, but with a day-to-day account they appear most unlikely. Back in England, Goodall took a crash course in primatology with John Napier, a comparative anatomist, to prepare for her fieldwork. At the same time, unbeknownst to Goodall, Leakey was offering her job to an American graduate student who, unlike Goodall, had a degree in anthropology. Fortunately for Goodall, the student eventually turned down the offer. Goodall, meanwhile, had found a fiancé, although the relationship would not survive her long absence.

When Goodall finally headed to the field in the summer of 1960, the Tanganyikan authorities would not let a white woman camp alone at Gombe, so her heroic mother, Vanne, came along as chaperone. There were other difficulties: the first trip was only financed for four months; Jane carried fuzzy borrowed binoculars and an inadequate camera; and once she was finally established, the chimpanzees were mostly invisible.

Day after day she clambered to a vantage point above her camp where she could survey the wooded valleys. "The Peak," as Goodall began referring to this spot, sits high in the rift mountain range that rises from the lake—no wonder at times it was less tiring to sleep there overnight than to trek down to camp and up again. Zoologist George Schaller and his wife, Kay, visited in October. It was "really nice to talk to someone," Jane wrote home, "who didn't think I was completely crazy." Schaller, fresh from watching the vegetarian mountain gorillas, remarked that if Goodall spotted chimps eating meat or using a tool, she would have the clout to continue her study.

She would witness both within just a few weeks of the Schallers' visit. She discovered meat eating, meat sharing and tool making (in this case, dipping long stalks of grass into termite mounds to "fish" for termites) in that first brief season. After Goodall reported this last finding to Leakey, he sent his famous reply by telegram: "Now we must redefine ‘tool,' redefine ‘man,' or accept chimpanzees as humans."

Leakey was able to use Goodall's breakthroughs to secure new funding from the National Geographic Society. Goodall continued her studies and eventually recorded the male display she called the "Rain Dance." After a year of work at Gombe, she wrote in a letter home that "now life is so wonderful. The challenge has been met. The hills and forests are my home. And what is more, I think my mind works like a chimp's, subconsciously. . . . It's most peculiar." As Peterson adds,

Perhaps her most impressive accomplishment was to recognize that chimpanzees have minds in the first place. . . . [N]ot that these apes eat meat, make and use tools, dance wildly in the rain, and all the rest, but rather that they do such things as active and willful beings with personalities, beings who inhabit an intellectual world similar to our own. . . . That slowly appreciated truth was the real magic behind her first year at Gombe.

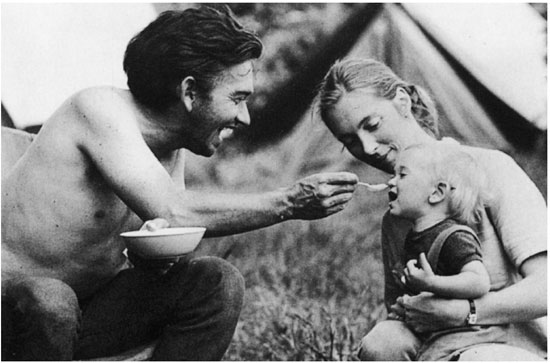

From Jane Goodall.

The saga continues. Goodall may seem the poster girl of the National Geographic Society, but over the years its board repeatedly came within inches of withdrawing its support. She met and, in 1964, married photographer Hugo van Lawick, aided him in his work on the Serengeti, and bore and raised their son. But the couple separated in 1972, and the marriage ended in divorce. Goodall fell in love with Derek Bryceson, a minister in the government of Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere. Bryceson and Goodall were married in 1975, but, tragically, he died of cancer in 1980. Goodall juggled love, motherhood and the details of her husbands' lives, not to mention the repeated financial and personal crises of the Gombe Stream Reserve, along with the perpetual struggle for time to write the next book or article. Her story is much more complicated than the idealized picture of beautiful Jane alone in the wilds.

In addition to recounting Goodall's life, Peterson describes the state of primatology at the start of her career: the behaviorists' icy denial of innate disposition, and the seminal work of Wolfgang Köhler, Robert Yerkes, Harry Harlow, Adrian Kortlandt and the Japanese primatologists who followed the teachings of Kinji Imanishi. Peterson also summarizes Goodall's contributions to the field:

Jane Goodall had demonstrated that it was possible to live and walk freely among wild chimpanzees, and that a person—even a bare-legged, pony-tailed, young female one—could over time and with great effort construct a critical understanding of what wild apes do, how they live, and who they are. . . . She propagated the idea that wild chimpanzees have emotions similar to those of humans. . . . [S]he was the first or among the first proponents of the idea that chimpanzee behavior exists in a cultural context. . . . Jane Goodall practiced and taught a science that combined the cold purity of traditional European ethology with her own warm embrace of intuitive and ethical ways of thinking.

Goodall's continuing influence derives from more than just the huge network of primatologists who have worked at Gombe and the ongoing research on both chimpanzees and baboons at the reserve. She would probably cite instead the success of her Roots and Shoots Clubs in 40 countries, which give young people inspired by conservation the opportunity to reach out to their peers in other nations. She would describe the changes in housing and care of captive apes that have come about as a result of her campaigning. Perhaps most of all, she would discuss the work of the Jane Goodall Institute, which is now a principal source of support for a million people who live close to the Gombe Stream Reserve. The institute deals with everything from reforesting eroding hillsides to education for girls to breeding hybrid oil palms that bring cash into the local economy. It is there that the Roots and Shoots Clubs and the adults who work as development agents or full-fledged researchers connect the practical needs of human life with the survival of Gombe chimpanzees and their islanded reserve.

It is impossible to visit Gombe today without seeing the area and the chimpanzees through the prism of Hugo van Lawick's photographs and Goodall's writing. Gimli, a two-year-old chimp, picks up the end of a stick, a sketch of a future when he will hurl branches in charging display. Beside him stands Flint, immortalized in just the same gesture 40 years ago. Gremlin, the matriarch, commandeers a newborn grandchild, clearly convinced that she is a better caretaker than young Gaia, the baby's mother. The infant's pink starfish hands clutch its grandmother's belly fur just as Gremlin clung to her own mother, Melissa, three decades before. Gremlin's family owes their continued, apparently timeless, existence to Jane Goodall—and to the understanding that the Jane Goodall Institute helps to create among the humans around them.

Come back to the lecture that opens the book. The silver-haired wise-woman knows how to hold an audience in her hand. Her hearers gasp and weep. But the basis of her hold is not mere personality. It is the force of her insight and the urgency of her message.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.