This Article From Issue

November-December 2019

Volume 107, Number 6

Page 376

NO SHADOW OF A DOUBT: The 1919 Eclipse That Confirmed Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. Daniel Kennefick. 403 pp. Princeton University Press, 2019. $29.95.

EINSTEIN’S WAR: How Relativity Triumphed amid the Vicious Nationalism of World War I. Matthew Stanley. 390 pp. Penguin, 2019. $28.

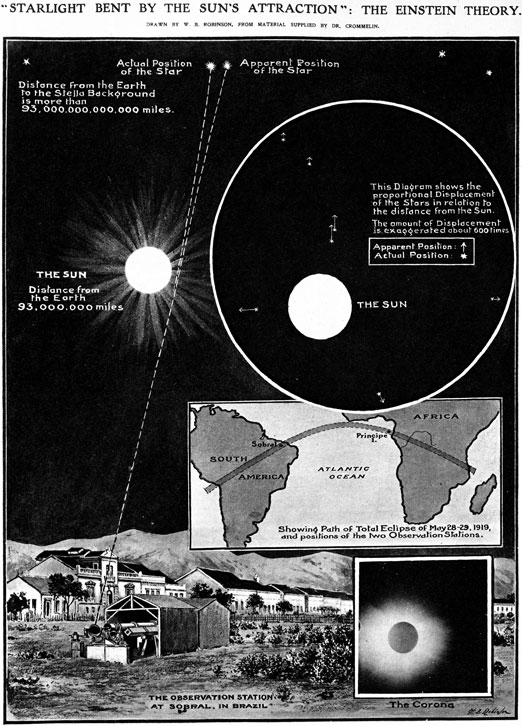

This year marks the centenary of perhaps the most famous pair of expeditions in the history of modern science. In early March of 1919, two parties set out from England for separate locations from which they planned to observe a total solar eclipse on May 29. Their intent was to determine whether the paths of light from distant stars “bend” as they skim the outer edge of the Sun. The darkness brought on by the eclipse would make it possible to see stars near the Sun clearly and therefore to measure changes in their apparent position. If a deflection of starlight by the right amount were found to occur, one of the most famous predictions of Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity would be confirmed. Space would be shown to be curved and light would be shown to travel on a curved path around a massive body.

One of the eclipse parties, led by the English Quaker astronomer Arthur Stanley Eddington, who was director of the Cambridge Observatory, was journeying to the island of Príncipe, off the west coast of Africa. The other group, a team from the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, was being sent to Sobral in Brazil by the Astronomer Royal, Sir Frank Watson Dyson, who was collaborating with Eddington. The two groups reached their respective destinations in late April, leaving them plenty of time to get set up for the eclipse on May 29. The weather at Sobral that day was perfect. On Príncipe it was overcast, but the clouds appeared to part a little, and Eddington professed himself “hopeful.”

Results took considerable time to process, but when they were announced later that year, they were described as confirming Einstein’s predicted amount of deflection of starlight, and the public response was little short of astonishing. “Revolution in Science,” trumpeted a headline in the Times of London. “New Theory of the Universe” and “Newtonian Ideas Overthrown” read the subsequent subheadings. While some may have struggled to follow the technical details of the results, few could miss their political symbolism. Einstein himself would note that symbolism in an article in the Times a few days later, lauding—only a year after the end of World War I—the “high and proud tradition of English science” that led to the testing of “a theory [general relativity] that had been completed and published in the country of their enemies in the midst of war.”

From No Shadow of a Doubt.

Most scientists, particularly in Britain, seem to have been convinced by the claims of Eddington and Dyson. Einstein’s prediction and its confirmation were soon celebrated as exemplars of scientific practice. More than half a century later, however, a backlash against the expedition’s claims began. It came to a head in 1980, when two philosophers, John Earman and Clark Glymour, published a paper titled “Relativity and Eclipses” in the journal Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences. They suggested that Eddington had been blinded by his enthusiasm for Einstein’s work: that he had been swayed by its international symbolism in a world struggling to heal the wounds inflicted by war; that he was biased in Einstein’s favor, because he himself was a pacifist and internationalist; and that this lack of objectivity resulted in Eddington mischaracterizing the data itself.

We need a little detail to understand Earman and Glymour’s charges. Two instruments had gone to Sobral, but the scientists on Príncipe had only one. What was being measured were tiny displacements in the positions of stars right next to the bright eclipsed Sun, so the observations were not easy to make. As noted, the observations at Príncipe were marred by cloud. Of the 16 photographic plates obtained, only two were usable. The sighting at Sobral, by contrast, was fine, but the astronomers were worried about the troublesome coelostat they used to track the stars as the Earth moved. One set of the Sobral data suggested a deflection of starlight of 1.98 arcseconds, which was a little high but close to the value that Einstein had predicted in 1915: 1.75 arcseconds. The second set of Sobral data gave a mean deflection of 0.86 arcsecond. This was very close to the value Einstein had calculated in 1911 (0.87 arcsecond), before he had incorporated the curvature of spacetime into his general theory. This came to be known, somewhat misleadingly, as the “Newtonian” value, since it relied on the assumption of “Newtonian” space, even though Isaac Newton himself had never made such a calculation. Meanwhile, the Príncipe data, seemingly the least accurate, gave a value of 1.61 arcseconds—a little lower than the 1915 value, but unquestionably higher than the “Newtonian” number. Working through the results in the six months after the observation, Eddington and Dyson came to the conclusion that they should ignore the data from Sobral that seemed to go against Einstein’s full theory, and should rely instead on the data from Príncipe, using the other Sobral data as support. Einstein, they declared, was correct.

From No Shadow of a Doubt.

According to Earman and Glymour, Eddington displayed a clear bias in reaching this conclusion, a bias that “showed in his treatment of the evidence.” Their 1980 paper became the backbone of a discussion of the case in The Golem: What Everyone Should Know about Science, a widely read 1993 book by two sociologists of science, Harry Collins and Trevor Pinch. By the time I began studying the history of physics in the mid-1990s, it had become fairly standard to believe that Eddington had gone substantially further in supporting Einstein than his data really warranted.

A counter-backlash had already begun with the work of historian of science Matthew Stanley, who published an article on Eddington and the 1919 eclipse in the journal Isis in 2003 and then treated the subject more comprehensively in his 2007 biography of Eddington, Practical Mystic. In May 2019, to mark the expedition’s centenary, Stanley published Einstein’s War: How Relativity Triumphed amid the Vicious Nationalism of World War I. In 2012, astrophysicist and historian of science Daniel Kennefick published a defense of Eddington’s methods in an article included in the book Einstein and the Changing Worldviews of Physics, edited by Christoph Lehner, Jürgen Renn, and Matthias Schemmel. Like Stanley, Kennefick has published a book this year for the centenary of the expeditions, titled No Shadow of a Doubt: The 1919 Eclipse That Confirmed Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, in which he has considerably expanded upon and deepened the arguments he made in his 2012 article.

Kennefick’s arguments may be boiled down to three main points. First, Eddington had good scientific reasons to favor Einstein’s gravitational theory, because Einstein’s kinematic theory of special relativity had already posed insurmountable problems for Newtonianism. If Eddington was “biased” toward Einstein, then it was more because of their common scientific interests than on account of their shared politics. Second, as Stanley had already argued, Eddington did not go beyond standard and broadly acceptable scientific practices in deciding to weight some of the eclipse data over others. That said, in judging whether Eddington should have trusted the Príncipe data, some suspicions may remain. Eddington’s “admitted biases,” Kennefick acknowledges, “might have made him especially anxious to extract a result from data that another experimenter would have been tempted to discard.” Concerning the exclusion of the Sobral data, on the other hand, Kennefick makes his third, and most convincing, case in Eddington’s favor. For it seems clear that Eddington was neither present during the reduction of the Sobral data nor privy to the decision to exclude results that seemed most strongly to favor a “Newtonian” amount of deflection. That work was done by Dyson, and it is hard to make a case that Dyson had some unusual bias toward Einstein’s theory or political views.

From No Shadow of a Doubt.

Almost anyone with a scientific soul should thrill to the tale of the 1919 expeditions. Profound scientific ideas mingle with equally profound human stories. Kennefick guides the reader well, although at times details threaten to swamp the central narrative. Those interested in Science Studies (an interdisciplinary research area that considers the social, historical, and philosophical contexts of scientific expertise) will also find in No Shadow of a Doubt abundant material with which to reinvigorate now-classic debates about the ways in which preconceived ideas may or may not shape the acceptance of scientific work. Even if shadows and doubts about the 1919 findings remain, this thoughtful and rigorous book at least lays several old myths to rest.

At the heart of Kennefick’s book are the two 1919 expeditions. At the heart of Stanley’s book are two struggles and the twinned biographies of two men: Eddington and Einstein. One of the struggles is portrayed as being largely Einstein’s alone, his “personal war”: the effort not only to produce his theory of general relativity, but also to convince others of its value, particularly in the context of a world-encompassing conflict. This personal war was taking place during World War I and was intertwined with that conflict. “Without the Great War,” Stanley writes provocatively, “relativity would not be as we know it, and Einstein’s name would not be synonymous with genius.”

Of all the allies that Einstein would make, Eddington would be the most important, even though their connection turned on slight events. Word of German developments in physics was hard to come by in Britain. Eddington learned of Einstein’s new theory not from Einstein himself, but from the director of the Leiden Observatory, Willem de Sitter, who sent Eddington a letter summarizing general relativity and discussing its implications. That letter marks the first time, Stanley tells us, that general relativity “leaped the trenches,” reaching Allied hands. De Sitter had chosen the perfect recipient. Not only was Eddington one of the few people in Britain capable of understanding the theory and its forbidding mathematics, he was also one of the few scientists in Britain willing to pay attention to, and even celebrate, a “German” theory. Eddington would learn relativity from de Sitter across the summer and fall of 1916. He also learned of Einstein’s politics. “I was interested to hear,” he wrote his Dutch colleague, “that so fine a thinker as Einstein is anti-Prussian.” Einstein became the perfect symbol for Eddington’s struggle against the “vicious nationalism” of his compatriots. German science could not be dismissed when Einstein could be made to represent the value of brilliant scientific internationalism.

Kennefick does a fine job of explaining the significance of the 1919 expeditions to science and international politics. Stanley manages to convey—in prose that captures both scientific and emotional complexity—what general relativity meant to the men who made it famous. Interested readers probably already know this story in Einstein’s case, for it has been told many times, although rarely as well as in Einstein’s War. What the expeditions meant to Eddington, however, is far less well-known, and Stanley explains it through a seemingly unlikely mechanism: Eddington’s attempts, as a Quaker and hence a pacifist, to be recognized as a conscientious objector. (Einstein, too, was a pacifist, but as a Swiss citizen, he was spared conscription.)

Eddington was originally given an exemption from military service. The exemption had been applied for by the University of Cambridge, on the basis of the importance of Eddington’s scholarly work at the observatory. The university had little interest in the public relations fiasco that would follow if the press reported that one of its most illustrious dons refused to serve. Eddington found the exemption insufficient. He was refusing to fight because of his religious convictions, and he wanted this fact registered. He filed his own form as a conscientious objector, but the university apparently made sure that it was never processed.

In 1918, however, the government revoked all occupational exemptions. Eddington would have to make his case to the Cambridge Tribunal. That case would be complicated, but it boiled down to a single, intractable point of contention. Eddington refused— repeatedly—to have his exemption accepted solely on the grounds of his national importance, rather than on the grounds of his religious beliefs. The tribunal, however, refused to accept that Eddington had grounds, as a scientist, to make a religious claim. Eddington could either be a scientist or a Quaker. He could not, as far as the tribunal was concerned, be both.

In the end, however, Eddington did accept an exemption on occupational grounds: Dyson managed to convince the tribunal that the eclipse expedition was of such national importance that Eddington should be excused from military service. Eddington went along with this compromise because, Stanley explains, Eddington saw his expedition itself as “a kind of pacifist statement— it was a way to demonstrate to the world of science that pacifism and internationalism was superior to patriotism and war.” The expedition—which combined Swiss-German theorizing and British observation—was brilliant science and Quaker service.

Stanley’s is a superb book, one that scientists, historians of science, and the general public will enjoy in equal measure. It is written for a wide audience. Those wary of technical jargon will be delighted by Stanley’s lucid explanations. With almost all books written in a generalist vein, there is some worry about what might be lost—however much else is gained—by not dwelling on the details provided in the academic work on which they are based. Einstein’s War, however, is that very rare work from which I came away understanding the scholarly literature better for having had its context presented to me in gripping and readable prose.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.