This Article From Issue

March-April 2021

Volume 109, Number 2

Page 118

THE APOCALYPSE FACTORY: Plutonium and the Making of the Atomic Age. Steve Olson. 336 pp. W. W. Norton, 2020. $27.95.

In The Apocalypse Factory: Plutonium and the Making of the Atomic Age, science writer Steve Olson walks readers through the development of nuclear weapons science, chronicles the construction and operation of the primary plutonium production complex for U.S. nuclear weapons, follows its product as it undergoes fission above cities and deserts, and gives us a small glimpse of ongoing efforts to deal with the domestic fallout of contaminated bodies, buildings, water tables, and soils. He does this from the perspectives of those involved, while describing the relevant science and engineering in engaging and approachable ways. This embodied perspective becomes particularly compelling as Olson describes the immediate aftermath of the Nagasaki bombing through the eyes of a surgeon who survived the blast.

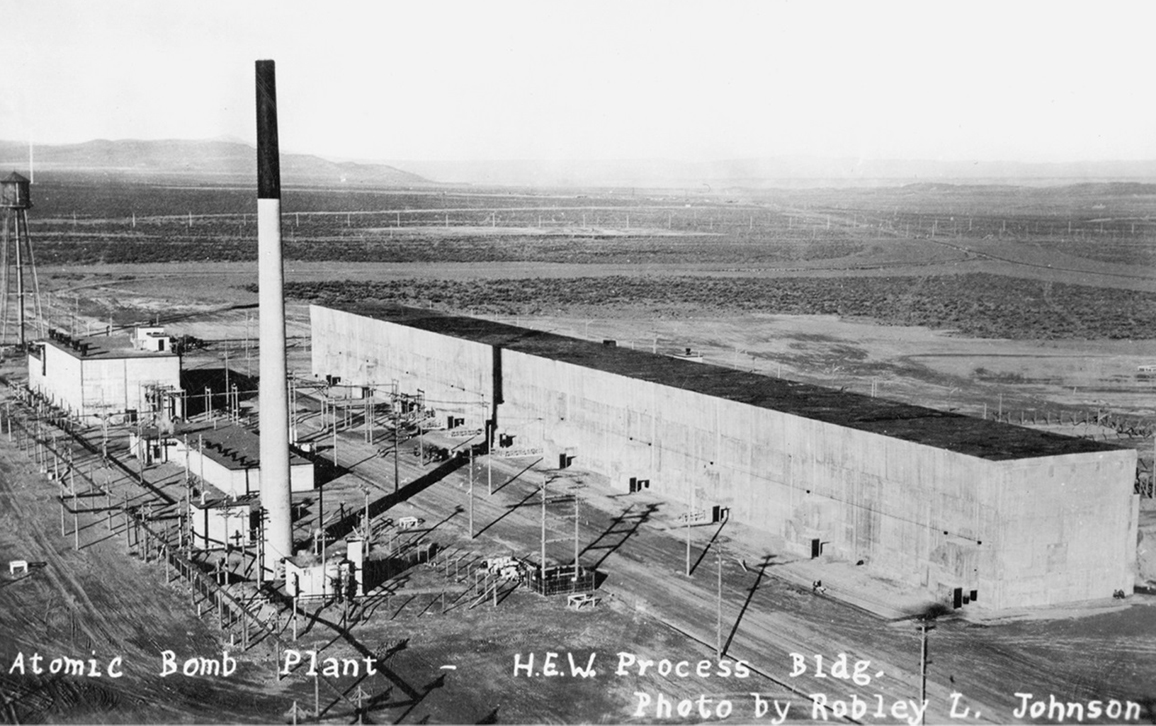

Olson is attempting to address a tendency in the historiography of nuclear weapons to focus on laboratories such as Los Alamos and the eminent physicists who worked there, rather than on sites of production and the engineers, chemists, and others involved in ushering in the nuclear era in which we still find ourselves. The “factory” referred to in the book’s title is the nuclear production complex known as the Hanford Site, which abuts the Columbia River in southeastern Washington State near Olson’s childhood home. Although the bomb that was tested at the Trinity Site in New Mexico and the “Fat Man” bomb that destroyed Nagasaki were designed and assembled at Los Alamos, the plutonium fueling those devices and most subsequent nuclear weapons made in the United States was produced on the banks of the Columbia in reactors cooled by its waters.

Olson mostly focuses on Hanford’s origins and early years, arguing that the site holds vital lessons for survival and repair in the nuclear era. Elucidating the book’s title, he notes in an epilogue that

in the Bible, an apocalypse is not the final battle between good and evil--that's Armageddon. . . . An apocalypse is a revelation—literally an uncovering—about the future that is meant to provide hope in a time of uncertainty and fear."

In Part 1, “The Road to Hanford,” Olson guides us through the scientific discoveries and early days of the Manhattan Project. We see events largely through the eyes of chemist Glenn Seaborg, who first isolated plutonium using the highly toxic chemical processes later employed on an industrial scale to separate plutonium from the spent fuel of Hanford’s reactors. As Olson relates Seaborg’s contributions, he weaves into that story descriptions of some of the most consequential years of nuclear chemistry, the creation in secret of the first nuclear reactor (Chicago Pile 1), and the sometimes-tense relationship between scientists and military officials, which continued into the postwar period.

From The Apocalypse Factory

In Part 2, “A Factory in the Desert,” Olson describes the construction and early operation of the Hanford Site, the Trinity test of the first atomic bomb, nuclear weapons design at Los Alamos, and the contentious discussions about how and whether to use these new weapons. We see these events not just through the eyes of nuclear scientists but also from the perspective of workers and military officials. Olson does a particularly good job of introducing physicist Leona Woods, a neglected figure in the historiography of the Manhattan Project. Woods was a young physicist from Illinois who worked alongside Enrico Fermi on the Manhattan Project and was often the only woman in the room. She was instrumental in solving the xenon poisoning problem that almost led to the failure of Hanford’s B Reactor, which was the first industrial-scale reactor in the world. Finally, we also visit Tinian Island (the launching point for the atomic bomb attacks against Japan) and follow the crew of the Bockscar (the B-29 bomber carrying “Fat Man”) as they fly toward Nagasaki.

Part 3, “Under the Mushroom Cloud,” is the most powerful portion of the book. In it, Olson describes the bombing of Nagasaki and its aftermath as seen through the eyes of Raisuke Shirabe, who was a surgeon at the Nagasaki Medical College Hospital. We witness his initial confusion and terror as his office becomes a blinding whirlwind when the bomb is detonated, as well as his efforts to evacuate and care for survivors, and his reunion with the surviving members of his family. We are with him as patients, including his son, begin to die mysteriously of what turns out, of course, to be radiation sickness.

At times, the reader loses track of the fact that the scientists, engineers, workers, and others whom Olson so sympathetically describes are building weapons of mass destruction that will eventually be used in what many regard as war crimes. Olson doesn’t quite take a firm stance on such matters, but by letting us see the consequences of their work through Shirabe’s eyes, he eliminates the abstraction with which these events are so often spoken of. Seeing the bomb from the perspective of embodied survivors has a more powerful impact than do casualty figures, descriptions of airplane cockpits, and discussions of war strategy.

In Part 4, “Confronting Armageddon,” Olson writes about Hanford’s Cold War history, the struggles of the local communities that were exposed to Hanford’s emissions, the beginning of environmental remediation efforts at the site, and the work of the B Reactor Museum Association and others who have made Hanford into a site of historical preservation and education.

There is a tendency in the telling of Hanford’s history—and the history of nuclear weapons more broadly—to focus on origins. The Manhattan Project is always rightfully treated as an important historical event, but the Cold War–era nuclear complexes and the era of remediation and tenuous survival in a world with nuclear weapons and nuclear wastelands are just as relevant and interesting. Indeed, Olson seems to indicate that the most significant “apocalypse” might be found in the much longer era of repair in which we now find ourselves. “We have many more things to clean up in this world,” he says. “Hanford’s cleanup, if done persistently and well, could provide an object lesson in making the Earth whole again.”

Like Olson, I also find hope and lessons for the future in the monumental effort to address the legacies of plutonium production on the Columbia Plateau. But I wish that he had devoted more pages to this complicated, contentious, and even heroic work of repair. Readers would have benefited, for example, from a deeper dive into the fascinating science and engineering of the remediation happening at Hanford now. However, remediation is nearly always accorded less prestige and attention than bomb making.

There are also many important lessons to be learned from the postwar Indigenous history of the site, but unfortunately, Olson says relatively little about that history. Hanford is the site of major violations of the treaty rights of the Yakama, Umatilla, and Nez Perce nations, who have long-lasting religious, cultural, and historical ties to the area. In the United States, the nuclear complex and nuclear history have impinged on Native American lands and bodies in a number of places, including at the proposed repository at Yucca Mountain in Nevada. Hanford’s continuing violation of treaties, the politics of consultation with federal agencies, and the ways in which the arguments of tribal governments are too often ignored—these are topics that deserve a book of their own. Attention to this history would also have the beneficial effect of complicating the pervasive assumption that environmental remediation is a technical project that can be easily divorced from social, cultural, and political issues.

Despite these missed opportunities, The Apocalypse Factory is an excellent and engaging introduction to the history of Hanford and the Manhattan Project. Readers will appreciate Olson’s ability to describe complicated scientific and technical matters while connecting them to both biography and history. He also leaves readers with a vitally important imperative that is too often treated as hopeless idealism: the need to abolish nuclear weapons through the international control of the products of apocalypse factories such as Hanford.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.