Interface Facts

By Katie L. Burke

Video games allow people all over the world to do scientific research

Video games allow people all over the world to do scientific research

DOI: 10.1511/2012.99.463

People spend 300 million minutes every day playing Angry Birds, one of the world’s most popular video games. What if we could tap into that energy to solve real-world puzzles? In 2003, Carnegie Mellon University computer scientist Luis von Ahn, now known as a crowdsourcing pioneer, asked this question and answered it with the ESP Game, in which people score points by giving an image the same label as someone else. By 2006, 10 million images had been labeled, and that year Google bought the game, launching von Ahn’s career.

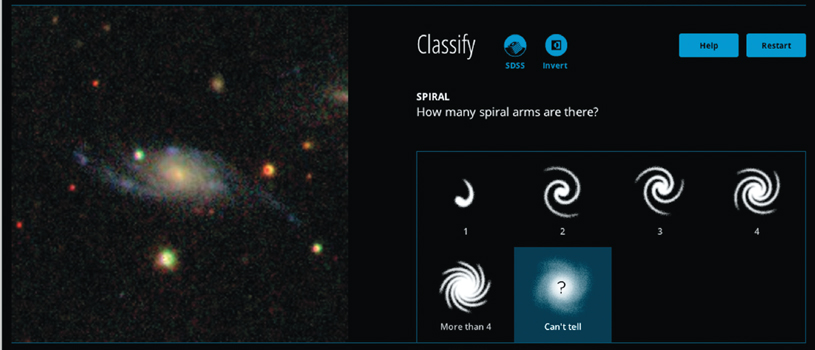

Photograph courtesy of GalaxyZoo.org/SDSS.

In the wake of ESP Game’s success, scientists across a variety of fields caught on: When they needed information from large datasets that could not be collected by a computer, people could help. Although public participation in scientific research is not a new idea—for example, the Audubon Society’s first Christmas Bird Count took place in 1900—the advent of greater computing power and the Internet have facilitated faster, more widespread information sharing than ever before. Not just hundreds could participate, but hundreds of thousands could interact through a web interface. The field of citizen science took off.

The success of early computer-based citizen science projects, such as Stardust at Home, showed that huge numbers of people around the world were willing to contribute computing power and time to making discoveries. In Galaxy Zoo , launched in 2007, participants classify images of galaxies by shape, and that information is used to extrapolate their history. Galaxy Zoo was an unexpected success: Twenty-four hours after the project launched, it was clocking 70,000 classifications per hour. Chris Lintott of Oxford University, one of the creators of Galaxy Zoo, says: “We were completely overwhelmed and pleasantly surprised by the sheer number of people who wanted to help.” Galaxy Zoo resulted in discoveries such as the Voorwerp, a strange, giant gas cloud noticed and named by Dutch schoolteacher Hanny Van Arkel. Galaxy Zoo astronomers are using the Hubble Space Telescope to figure out the nature of the Voorwerp and smaller Voorwerp-like gas clouds. “It looks like nothing I’ve ever seen. They’re much more crazy complicated structures than we ever thought,” explained Lintott.

Collaborating with colleagues from around the world, Lintott went on to create the Zooniverse , an Internet home for popular citizen science projects across disciplines. In the Zooniverse, anyone can participate in research on whale calls, weather as recorded in wartime ship logs or new planets. “These projects create very personal connections to an often quite obscure category of science,” Lintott explains. The group has another compelling reason to run these diverse projects: to study what people want to do and what they are good at. Lintott notes, “I was incredibly grateful that all these people wanted to classify galaxies, but I didn’t understand what magic thing it was about Galaxy Zoo that made it work. You can think of all the projects in the Zooniverse as an exploration of that space.”

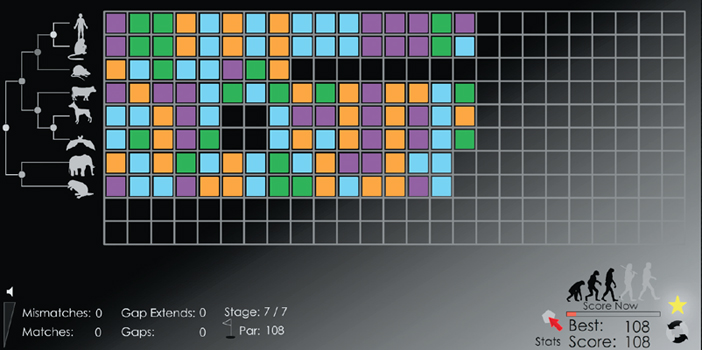

Online citizen science games are modeled after video games that motivate participants to score points and achieve new tools and levels. For example, FoldIt , a game based on Rosetta at Home and launched in 2008, prompts players to decipher potential 3D protein structures associated with particular pathologies, such as a retroviral protease enzyme key to virus propagation in a form of AIDS found in monkeys. (An interview with the lead designer of FoldIt, Seth Cooper, will be posted on American Scientist ’s website.) With such high-profile successes, more online citizen science games were launched. In 2010, the Tetris-like game Phylo debuted, prompting players to win points for correctly aligning related DNA sequences. Mathieu Blanchette of McGill University, a member of the team that created Phylo, explains, “The main goal of Phylo is to bring together computers and humans, make each do what they are good at, and put the results together to get something better than either could get alone.” A March 2012 paper in PloS One announced that 70 percent of the alignments in the game had been improved by the more than 26,000 registered Phylo users, as well as tens of thousands of unregistered users.

Photograph courtesy of Phylo, McGill University.

But what works for one citizen science project will not necessarily work for another. FoldIt players must invest large amounts of time advancing through tutorial levels before they have the skill to contribute to real-life research. Players seem undeterred by this requirement: FoldIt has some 240,000 registered users and counting. Alternatively, Galaxy Zoo and Phylo are interfaces where users need no prior knowledge of the science and can spend a few minutes of their time in order to contribute to research. Said Phylo collaborator Jérôme Waldispühl of McGill University, “The simplest puzzles are as useful as the most complicated ones for improving our alignments.” In contrast to FoldIt and Phylo, Galaxy Zoo and other Zooniverse projects are deliberately not structured as games—they lack scores or levels. As Lintott explains, “The instinct to play a game is incredibly powerful, and once you trigger that, it’s very easy to switch somebody’s motivation from ‘I want to help science’ to ‘I’m playing this game.’” According to Lintott, when that motivation switches, the best and worst players are more likely to stop playing. Therefore, only some online projects benefit from a game interface.

Perhaps no one should have been surprised that people participating in these projects do not balk at complex problems, even ones that require programming and simulations. Zooniverse collaborators expanded Galaxy Zoo’s idea into Galaxy Zoo Mergers, in which users control simulations of galaxy collisions. “We discovered by accident that if you give access to as much information as you can behind a task, people take it and run an awfully long way. You find people who would never have dreamed of reading textbooks or searching scientific literature wandering through the web because it’s their galaxy and they want to know about it. Providing the tools for that sort of deep exploration has become important,” says Lintott.

The field of computerized citizen science is advancing quickly, altering how research is done as well as how science is perceived and taught. “We’re living in a society where human and computer are fully integrated,” says Waldispühl. The Zooniverse has recently released a few new projects and will be releasing more in the coming months. Phylo is opening an interface with which researchers will be able to submit genome sequence alignments they need help improving. Some FoldIt creators went on to launch EteRNA , a game for designing RNA. The Zooniverse team is also using information garnered from their games to improve computers’ ability to identify visual patterns, so that the most difficult and unusual tasks are delegated to humans. Lintott predicts, “The next generation of datasets is going to be even bigger, and so we’re going to need to split the work between humans and computers, even with hundreds of thousands of people helping.”

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.