Pandora's Baby, Bicycling Science, The Mapmaker's Wife and more . . .

By David Schneider

Short takes on eight books

Short takes on eight books

DOI: 10.1511/2004.48.0

In the late 1970s, in vitro fertilization offered new hope to infertile couples and revolutionized our conception of conception. Robin Marantz Henig recreates the cultural and scientific climate of the infancy of that technology and draws some striking parallels to current cloning controversies in Pandora's Baby: How the First Test Tube Babies Sparked the Reproductive Revolution (Houghton Mifflin, $25). Doctors, lawyers, politicians and bioethicists wrangled with the potential risks, warning of slippery slopes. But less than a year after the birth of the world's first test-tube baby, in England in July of 1978, the U.S. government decided to allow this procedure. In a brisk and engaging style, Henig profiles the desperate couples, the pioneering—and occasionally irresponsible—doctors, and the often unscrupulous journalists drawn to the technology. Unfortunately, she devotes too much space to a 1973 civil lawsuit brought by a woman who considered the contents of a test tube to be her "baby" and a reclusive doctor who fabricated some of his results. The case, although it fueled a media frenzy and demonstrated how quickly people would embrace in vitro fertilization, contributed little to the history of how science changed our notion of where babies can come from.—F.D.

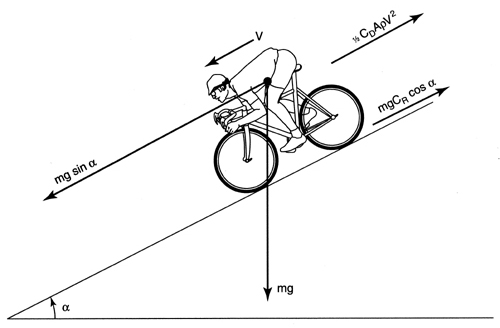

From Bicycling Science.

The next time someone uses that old saw "it's like riding a bicycle" to describe the ease of accomplishing something, direct them to David Gordon Wilson's Bicycling Science (The MIT Press, paper, $22.95). Not that Wilson and his contributor, Jim Papadopoulos, have made cycling more complicated than need be; rather, they have in 477 pages laid down everything the technically curious cyclist could want to know about his or her pastime. Is it physically possible that your buddy hit 100 kilometers per hour descending? (See right.) Can the heat generated by rim brakes burst a tire? You need only turn the page to find the answer.

This third edition of this bicyclist's bible is no rehash of the previous offerings in 1974 and 1982. In his preface, Wilson notes that Papadopoulos's expertise was particularly welcome in completely rewriting the chapter on "Steering and Balance." Here and in "Human Power Generation," for another example, a scan through the references reveals how much is new: About half the citations postdate the second edition's publication. But Bicycling Science does much more than scientifically dissect cyclists, cycling and bicycles. It gently dispels the mythology that so commonly surrounds bicycle technology, while encouraging the passion riders feel for the sport and the ingenuity and whimsy so often displayed by cycling's innovators.—D.R.S.

From The Mapmaker's Wife: A True Tale of Love, Murder, and Survival in the Amazon.

In 1733, France sent a team of scientists to colonial Peru on a momentous mission: to measure a degree of longitude near the equator. By comparing this with a degree measured in France, the academy could put to rest a longstanding dispute about the shape of the Earth. Was it flattened at the poles, as Newton argued, or elongated, as Descartes believed?

The team's adventures are recounted in Robert Whitaker's meticulously researched The Mapmaker's Wife: A True Tale of Love, Murder, and Survival in the Amazon (Basic Books, $25). Whitaker captures the voracious curiosity of the expedition's Enlightenment scientists, "set loose in a savant's playground." Together they explore South America, catalog its wildlife, document its culture and languages, and scale new heights in the Andes. Voltaire called their success "a model for all scientific expeditions to follow."

Whitaker contrasts this with the dark tale of Isabel Godin (right), who crossed the continent to rejoin her scientist husband in French Guiana after the expedition. Godin entered the Amazon jungle with a party of 40 and emerged four months later, exhausted, starving and alone. Her ordeal in the forest highlights the real dangers of colonial exploration and points up the achievements of what France called "the greatest expedition the world had ever known."—G.R.

From South Sea Islands: A Natural History

Photographer Rod Morris and zoologist Alison Ballance treat readers to a visually rich and wide-ranging tour in South Sea Islands: A Natural History (Firefly Books, $35). The package is so attractive, and the message—that isolated archipelagos show the many vagaries of evolution—is so forcefully illustrated, that it is easy to turn a blind eye to the occasional slipup in the text. What stickler cares, after all, that Hawaii, one of the stops on this 13-chapter journey from Fiji to Easter Island, is in the Northern Hemisphere? What does it matter that mammals evolved more than 100 million years before the authors say? And so what if the book fails to acknowledge Wallace and credits Darwin in unsophisticated ways? It is still full of many splendid details about the plants and animals seen on these (largely) tropical islands, such as the spectral tarsier from Sulawesi shown left. And having so many locales covered together provides a wonderful sense of the rules by which nature operates—and the exceptions to those rules.—D.A.S.

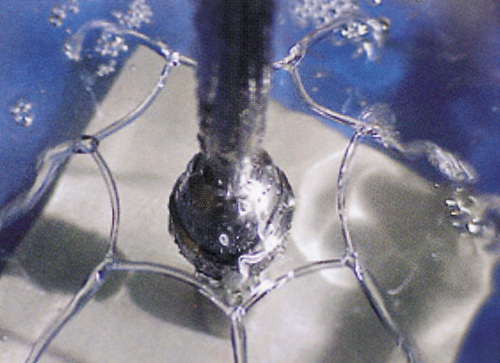

From A Gallery of Fluid Motion.

The many images collected by M. Samimy, K. S. Breuer, L. G. Leal and P. H. Steen, editors of A Gallery of Fluid Motion (Cambridge, $95 cloth, $35 paper), delight both the mind and the eye. These pictures, all winners of the "photo" contest held each year by the American Physical Society's Division of Fluid Dynamics, reveal everything from turbulent vortices in gas flames to polygonal umbrellas in fluid sheets (the latter is shown right). With each picture comes the short description that accompanied the winning entry when it was first displayed at the APS-DFD annual meeting. Written by the original investigators, these brief summaries authoritatively describe the physics behind these invariably intriguing, and often beautiful, depictions of fluids in motion.—D.A.S.

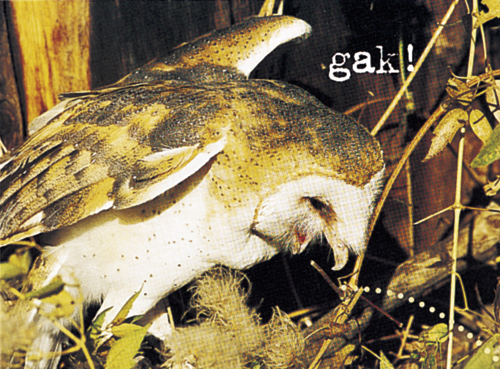

From Owl Puke.

Jane Hammerslough's Owl Puke (Workman, $13.95) imparts new meaning to the phrase "takeout food." This biology lab in a box, complete with a foil-wrapped ball of owl vomit, a bone-sorting tray and a guidebook detailing the birds' behavioral and culinary habits, should entice the 8- to 12-year-old set. It offers hands-on exploration of a modern circle of life: Owls eat their prey whole. Then, in the owl's gizzard, the indigestible parts (fur and bones) get compressed into "a smooth package of puke" that is regurgitated. Fungi, beetles and moths use this matter for food and shelter. And entrepreneurs (the guidebook informs us) sell it online for $1.65 per pretreated pellet (with a minimum 10-pellet order, please).

Fortunately, there's more to Owl Puke than a dried ball of vomit. Fully illustrated chapters covering important owl attributes and predator-prey relationships make the unwrapping of the pellet more meaningful. And young readers with a pair of tweezers, a magnifying glass and the patience to deal with small rodent bones can have a hoot putting together a skeleton.—F.D.

From M. C. Escher: Visions of Symmetry.

There is something oddly pleasing and intriguing about the interlocking forms that make up the artwork of Maurits Cornelis Escher. The repeating patterns display a range of symmetries that surprised and delighted mathematicians and crystallographers when the artist's work became widely known in the mid-20th century. Among these mathematicians was Doris Schattschneider, author of M. C. Escher: Visions of Symmetry (Abrams, $29.95), who couldn't stop wondering how the artist was able to produce images that captured many concepts in crystallography—some of which Escher had anticipated by 20 years! Schattschneider eventually found the answers in Escher's unpublished notebooks of 1941–1942, which she reproduces with translation and explanation in this revised edition of her 1990 book. This work contains more than 150 of Escher's images, many of which have not been published elsewhere. Although Escher usually performed his magic on flat surfaces, his talent also extended to three dimensions in wood carvings, such as the sphere "Heaven and Hell" (left), which he made in 1942.—M.S.

The Geese of Beaver Bog (Ecco, $24.95) is a true story about Peep, Pop, Jane and Harry—wild Canada geese (Branta canadensis) who've come to nest at a beaver pond near the woodsy Vermont home of author Bernd Heinrich. A biologist and astute observer of nature, Heinrich learned to identify the individual geese by their faces and then proceeded to chronicle their personal relations over several seasons as they took mates, raised young, formed alliances and squabbled with one another. Along the way he was witness to high drama: rejected spouses, mate swapping, jealousy, abandoned offspring and even what appeared to be goose depression after the surprising murder of some innocent goslings. Although Heinrich admits that his work with the geese is not hardcore science, there is much that students of animal behavior will learn by reading this insightful naturalist's thoughts on the personal lives of geese.—M.S.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.