This Article From Issue

September-October 2008

Volume 96, Number 5

Page 430

DOI: 10.1511/2008.74.430

FALLING FOR SCIENCE: Objects in Mind. Edited and with an introduction by Sherry Turkle. xii + 318 pp. The MIT Press, 2008. $24.95.

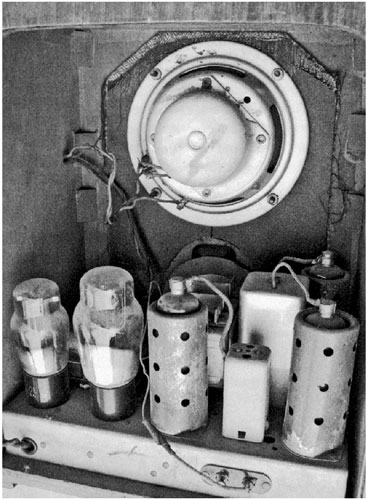

From Falling for Science.

"Some people are oriented primarily toward other people, others toward things." According to this folk belief, those children who gravitate toward "things" include budding scientists and engineers, whose adult relation to the world seems mediated more by scientific objectivity than by human emotion. If there is any truth to this view, much depends on what such object-orientation really means for the individual whose life it shapes.

In her pioneering book The Second Self (1984), Sherry Turkle argued that computers can serve their users not just as mute objects or tools but as alternative personae fraught with inner significance. Over the years since she began teaching at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1976 (where she is now Director of the MIT Initiative on Technology and Self and Abby Rockefeller Mauzé Professor of the Social Studies of Science and Technology), she has asked her students to write an essay responding to this question: "Was there an object you met during childhood or adolescence that had an influence on your path into science?" She has collected 51 of the more than 250 resulting essays (composed between 1979 and 2007) in her new book, Falling for Science: Objects in Mind, which she describes as "a book about science, technology, and love"—specifically, the ways the love of science may begin with a beloved object. Turkle rounds out this collection with eight essays from senior scientists responding to the same question, and the book is framed by her own extensive introduction and epilogue, which are eloquent statements in their own right.

The student essays open an interesting window into the inner lives of bright, scientifically oriented young people (15 of them women), who recall their favorite "objects," often formative toys and games, from the vantage point of their current lives. Their strikingly vivid descriptions also evoke the human milieus and associations within which these significant objects were embedded. The reader is left to wonder about the relation between the students' eventual careers and their early passions. Fully 41 of the 51 students have ended up in some strongly computer-centered field; none have become biologists, physicists or chemists, for instance, although the senior scientists who contributed essays include two biologists and an architect. Would the essays of students whose paths were not so predominantly linked with computers have looked different? Turkle says that the ones in this volume are representative of those she received. Could it be that, for this generation of MIT students, all science is essentially computer science?

Some of these students' chosen objects are what one might expect—LEGOs, sand castles, bikes, computers—but some are less obvious: chocolate meringue pie, the human body, a fly rod, My Little Pony (a toy pony with plastic mane and tail), siaudinukai (three-dimensional objects made by threading straws on string, a traditional Lithuanian craft). Turkle draws attention to the nuance and variation even within the seven essays that mention LEGOs.

Turkle's perceptive comparison of early "transparent" computers with the relative "opacity" of recent computer interfaces leaves one to wonder how this change might affect the way in which young people approach science through computers. Yet despite the lure of artificial digital worlds, she notes, young people are "always brought back to the physical, the analog, and of course, to nature."

This striking assertion leaves us to wonder about the relation between these generational, technological shifts and the ways "nature" may remain available to us. Indeed, some students recollect going back in time to rediscover the beauties of "transparent" vacuum-tube electronics. Perhaps the primal encounter with mud, sand and string will never be eclipsed, even by the most dazzling digital display. The generational comparison invited between the essays of the senior scientists and those of the students seems to bear out Turkle's conclusion that children's encounters with concrete as well as virtual reality will remain endlessly fruitful.

As Turkle notes, this fruitfulness has to do with the passion felt for an object, which can go beyond being a mere thing, taking on the aura of a love-object. The various notes of emotion in the students' stories challenge us to read them with commensurate responsiveness. As we do so, deeper questions emerge: What does it really mean to form such an emotionally charged relation with a (presumably nonhuman) object? In her introduction, Turkle mentions psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott's seminal concept of the "transitional object," which she reminds us is an object that "the child experiences both as part of his or her body and as part of the external world." For many children, transitional objects mediate between the object world and the human world: We learn to endure separation and loss through the beloved stuffed animal whose comforting presence helps lead us back to the human world again. In the light of this familiar story, these students' objects can be seen to mediate transitions to lives in science whose human dimensions we are only beginning to explore.

We need to think much more about how and why these objects can sustain such deep human feeling and, ultimately, what the full relation is between things and people. The students' stories suggest a spectrum of such relations, so that one wonders whether "object" and "human" can really be disconnected. Turkle's thought-provoking collection represents an admirable invitation to further exploration of science and human sensibility, of the mysterious web of human choice and feeling. There is much to ponder in her striking conclusion that "at a time when science education is in crisis, giving science its best chance means guiding children to objects they can love." This book shows us the human side of science that emerges when we develop strong feelings about the things of this world.

Peter Pesic, who is Tutor and Musician-in-Residence at St. John’s College in Santa Fe, New Mexico, is the author of Labyrinth: A Search for the Hidden Meaning of Science (2000); Seeing Double: Shared Identities in Physics, Philosophy, and Literature (2002); Abel’s Proof: An Essay on the Sources and Meaning of Mathematical Unsolvability (2003); and Sky in a Bottle (2005), all published by The MIT Press. He received the 2005 Peano Prize and is a Fellow of the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.