This Article From Issue

May-June 2016

Volume 104, Number 3

Page 182

DOI: 10.1511/2016.120.182

RUST: The Longest War. Jonathan Waldman. ix + 290 pp. Simon and Schuster, 2015. $26.95.

Those who combat rust for a living tend to agree on one point: It isn’t exciting.

In Rust , journalist Jonathan Waldman’s absorbing book on oxidation, workers in the corrosion business treat this claim like a mantra, even as their own words and actions contradict it. Bhaskar Neogi, the engineer responsible for the integrity of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, observes, “You can’t be in this business if you’re looking for excitement.” This, just hours after he drove through a flight-canceling snowstorm from Anchorage to Valdez to witness a high-tech vulnerability-sensing robot finish the last leg of its roller-coaster journey through the full length of the 800-mile pipeline.

John Carmona, proprietor of the Rust Store, contributes more cognitive dissonance. “Our products don’t make Christmas lists,” he says. “A gallon of rust remover isn’t necessarily exciting.” Yet his business, which he started in 2005, expanded steadily throughout the Great Recession. His inventory once took up two shelves in his garage; today it occupies a 10,000-square-foot warehouse. Over the years he’s become a kind of Dear Abby of rust, fielding a continual stream of inquiries—from the peacemaking spouse fretting over offending rust stains to a caller trying to eradicate staining at the stadium where the Indianapolis Colts play.

Then there is Dan Dunmire, head of the U.S. Department of Defense’s Office of Corrosion Policy and Oversight, who insists, “Corrosion’s not a sexy topic.” Yet he brings a singular energy to combating corrosion—“the pervasive menace,” as he calls it—enthusing, “My job is to make boring things fun.” His work has sent him around the globe, and he has won the admiration of NATO colleagues who base their practices on his, using a model they’ve named after him. The corrosion business opened the door for him to collaborate with one of his idols, actor LeVar Burton, on a series of training videos. What’s more, the U.S. Government Accountability Office has estimated that Dunmire’s projects average a 50-to-1 return on investment, shaming many a high-tech startup. The experts seem prepared to fade into the background, yet the importance of their work is conspicuous—much like rust itself.

Happily, Waldman ignored his subjects’ warnings about the topic’s potentially soporific effect and forged ahead, yielding an entertaining book crammed with fascinating tidbits and essential information. The World Corrosion Organization estimates the global annual cost of corrosion at $2.2 trillion, more than 3 percent of gross domestic product worldwide. The group states that this figure includes only corrosion’s direct costs, “essentially materials, equipment, and services involved with repair, maintenance, and replacement” of corrosion’s usual suspects, such as pipelines, bridges, vehicles, water mains, and sewer pipes. Not included, the organization notes, is the cost of “environmental damage, waste of resources, loss of production, or personal injury resulting from corrosion.” Nearly every organization, whether public or private, contends with corrosion. Waldman notes that “only a small portion of Fortune 500 companies—those in finance, insurance, or banking—are privileged enough not to overtly deal with corrosion.” For even these fortunate few, “corrosion is a major concern where their servers are stored.”

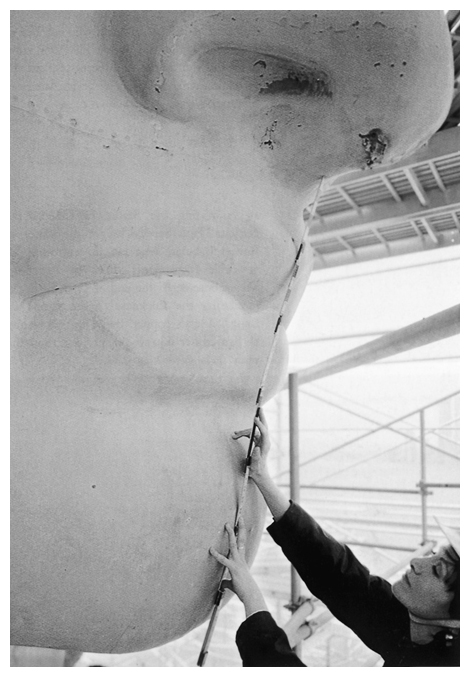

Most chapters focus on a particular aspect of corrosion (such as the chemistry involved or corrosion’s aesthetic potential) or on a related area of engineering (food and beverage canning, oil pipeline maintenance, galvanizing, or the development of stainless steel). Waldman proves a shrewd storyteller. My unscientific tests suggest he devised a specialized mixture, like a secret recipe for addressing corrosion: four parts research and legwork, three parts characterization, one part humor, and one part philosophy. He has a knack for suspense too, especially evident in his narrative of the massive public-private effort to restore the Statue of Liberty and his play-by-play account of the 2013 Trans-Alaska Pipeline inspection. While reading the pipeline chapter I struggled not to peek at its close, something I rarely feel tempted to do.

The massive amount of research Waldman must have undertaken to spin the marvelously immersive tales throughout the book is evident in Rust ’s wealth of historical details. The story of the 2013 Alaskan pipeline inspection winds its way through the history of that particular pipeline and through much of the history of oil transferal more generally. Constructing the narrative for this chapter and several others—the one on the massive Statue of Liberty renovation project, for example, and another on the founding and activities of the DOD’s corrosion office—must have required a mind-boggling number of hours digging through government records and corporate papers. (That said, I shouldn’t have to speculate about this facet of the work. Two pages of acknowledgments provide a broad sense of Waldman’s sources and methods, but the lack of a notes section was disappointing.) Waldman’s research also provides fodder for plenty of nifty historical asides. Among them, he offers up the first recorded mention of rust, by a Roman general who lamented that his troops’ catapults were so corroded they were “causing more casualties in our own army than to the enemy.”

For all the time Waldman logged in libraries and archives, as well as the frequent-flyer miles he must have racked up, the corrosion professionals who populate his book steal the show. Waldman is an acute observer, and he paints vibrant portraits of the specialists he shadowed. Extended segments focusing on Dunmire and Neogi as well as on Alyssha Eve Csük (an artist Waldman describes as possibly “the only person who makes a living finding beauty in rust”) read a bit like The Lives of the Corrosion Saints .

His admiration fizzes just below the surface as he describes Csük photographing a massive, decaying Bethlehem Steel Works blast furnace: “Over the next five hours, I watched Csük wander around a mazelike industrial complex of greater entropic value than a sub-Saharan market, calmly and boldly, without a map, in search of aesthetic minutiae that most people miss entirely.”

He notes occasional points of friction as well. When he presses Dunmire—who by all accounts, Waldman admits, handles his office’s funding responsibly—about the cost of producing his training videos, the ebullient, eccentric, Star Trek megafan and DOD bureaucrat grows testy. He grouches about the difficulty of isolating a figure, given the structure of the budget the videos share with related projects, and reminds Waldman how carefully he’s had to manage his team’s funds, modest by DOD standards, adding, “I’m a frugal sonofabitch.”

Corrosion specialists, it turns out, tend to be passionate about their work, however tedious they claim it to be. Each has a vision, and none is easily deterred. Some are true evangelists. Waldman argues that Harry Brearley, acknowledged as the father of stainless steel, is credited with the invention partly because he persisted in sharing his creation with anyone who would listen, until others began believing in its value as much as he did: “If anything, it was this tenacity—this quasi-insanity—that set him apart from earlier discoverers.”

As for Dunmire, his corrosion-battling passion is rooted in his concepts of service and responsibility. He repeatedly pushes his physical limits, maintaining an exhausting schedule to be sure he’s doing everything he can to “fight the good fight,” as he puts it, against corrosion—ultimately to ensure those serving in the military have equipment, infrastructure, vehicles, and facilities that are safe, durable, and reliable. Once a soldier himself, Dunmire is single-minded about his mission. “I’ll do anything for the warrior,” he says. “Without the warrior,” he adds, “We don’t have a country. Any discomfort that comes up, when you think about people giving up life and limb for this country, . . . I’ll put up with any bureaucratic bullshit anyone puts in front of me.”

The World Corrosion Organization estimates the global annual cost of corrosion to be $2.2 trillion.

Waldman rounds out Rust ’s colorfully peopled landscape with philosophical and lighthearted touches. Late in the book, he draws parallels between Neogi’s meticulous approach to pipeline integrity and the obsessive way the engineer cares for his beloved tropical fish. His pets occupy a 2,400-gallon tank tricked out with motion sensors, video camera monitors, two sources of backup power, and any number of devices that measure everything from dissolved oxygen to specific gravity. Each hour, 20,000 gallons of water flow through the tank, passing through filters Neogi built himself, which reside in a closet he converted into a custom-ventilated control room. A separate tank of coral further purifies the water. As Waldman observes, Neogi “has built a miniature simulacrum of a triple-redundant fail-safe pump station in his basement.”

Just when Waldman has made the case that rust is scientifically, economically, and artistically important, he throws the reader a curve and argues that rust is morally important too. Carmona, the pensive Rust Store proprietor, alludes to it: “There’s a subset of society that says, ‘Hey, what I’ve got is pretty good, and I’m going to maintain it.’ I think that attitude is what led me to open the store. I wanted to fix things up.” The people at the heart of these stories remind us to resist the enticements of a throwaway culture and to care about and attend to what surrounds us. “Dealing with rust,” Waldman says, “should give us a little more respect for what’s public, a little more regard for the future.”

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.