This Article From Issue

March-April 2001

Volume 89, Number 2

DOI: 10.1511/2001.18.0

Science Is Fiction: The Films of Jean Painlevé. Edited by Andy Masaki Bellows and Marina McDougall with Brigitte Berg. Translations by Jeanine Herman. xviii + 213 pp. The MIT Press/Brico Press, 2000. $39.95.

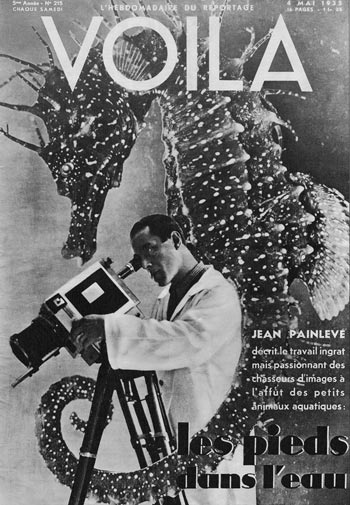

In this engrossing compilation of stills, storyboards, biographical and critical essays, and articles—the best written by Jean Painlevé himself and here published in English for the first time—we learn about a filmmaker who was Jacques Cousteau two decades before Cousteau went beneath the waves with a camera.

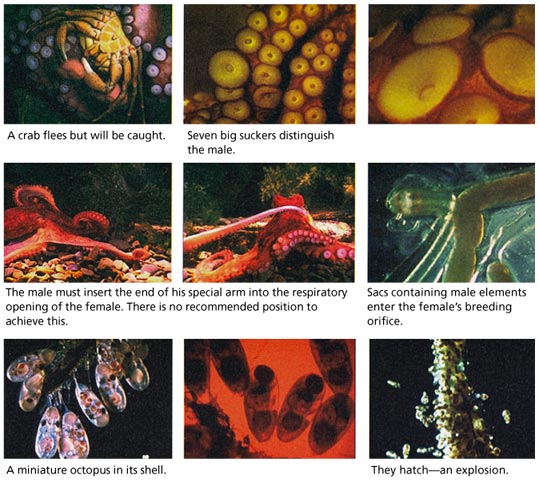

From Science Is Fiction

Unlike Cousteau, Painlevé was a trained scientist and remains an obscure figure. Despite having made more than 200 films in a career that stretched from 1927 to 1975 (he died in 1989), he is known chiefly to film historians like Andy Masaki Bellows and Marina McDougall, the editors of this volume. Thanks to their work here, Painlevé again lives among the great filmmakers and artists of his day: Jean Vigo, Antonin Artaud, Luis Bu?uel, Sergei Eisenstein (eight postcards sent by Eisenstein to Painlevé are included in the book!), Man Ray, Alexander Calder and others.

In a fine portrait that occupies about a quarter of the book, Brigitte Berg tells us that Painlevé was born in Paris in 1902, the son of Paul Painlevé, who later served twice as France's premier. Before becoming a filmmaker, he studied medicine and zoology. At age 21 he became the youngest researcher ever to present a paper (on color staining of glandular cells in midge larvae) to the Académie des Sciences.

At the time, film was developing into a serious narrative art form. Mindful that film had originated as a medium for documenting science, Painlevé sought to merge the documentary and narrative powers of film and, accordingly, sought the company of filmmakers. Cameraman André Raymond, in a film that was never completed, taught Painlevé a time-lapse effect he would use in his first film, The Stickleback's Egg: From Fertilization to Hatching. Painlevé presented the film to the Académie in 1928. The experience taught him that the mass acceptance of film made it to some a less desirable tool in science. Berg writes, "One scientist, infuriated, stormed out, declaring, 'Cinema is not to be taken seriously!'"

From Science Is Fiction

In the early 1930s, Painlevé made what was perhaps his most famous film, The Seahorse, for which he enclosed a camera in a specially designed watertight box for use in the Bay of Arcachon. Because the camera could only hold a few seconds of film, Painlevé was forced to return to the surface over and over to reload. Crude diving equipment limited his movement. His breathing apparatus was tethered by a 10-meter hose to a manually operated pump on a boat. Recalling the many challenges of early underwater cinematography, he wrote: "At one point I was no longer getting any air. I rose hurriedly to the surface to find the two seamen quarreling over the pace at which the wheel should be turned." The studio portion of the shoot also held frustrations: He and a collaborator spent three days and nights waiting outside large tanks for a male seahorse to give birth.

After hiding from Nazi collaborators during the war, Painlevé briefly served as director of the national cinema. Nine months later Charles de Gaulle replaced him with a bureaucrat. Painlevé went on to revive a group called the Institute for Scientific Cinema and helped create the International Association of Science Films, serving as its president. A running conflict in the group involved the definition of a science film. Painlevé ran into the same attitude he'd encountered years earlier in the Académie, that popular film was a form of prostitution and that popularization was, by definition, vulgarization.

In 1948 Painlevé became the first person in France to broadcast a live science program—teeming microbes in a drop of water. (A month later, repeating the shot for the BBC in London in another live broadcast, he became frustrated by technical difficulties and his lack of English, and his cry of "Merde!" was heard in 200,000 British homes.) His pioneering streak continued well into the 1970s, when he began experimenting with new techniques in video.

In addition to biography, Science Is Fiction brims with criticism, including a generous helping of Painlevé's own writing that, even in translation, remains so crisp it might have been written last week. "The Ten Commandments"—"You will not show monotonous sequences without perfect justification" and "You will not substitute words for images in any way" are among my favorites—wouldn't make a bad poster for today's film students. The title of "The Castration of the Documentary" is emblematic of his blunt, provocative style, as is the book's unfortunate and misleading title, based on a throwaway line he used to discourage pigeonholing of science films and to cut science snobs down to size.

By far the best new piece on the Painlevé aesthetic is Ralph Rugoff's essay "Fluid Mechanics." Rugoff notes that Painlevé's anthropomorphism is of a lost variety, not at all in the same vein as Walt Disney's nature films with their projection of "human values and emotions onto cuddly critters":

In Painlevé's hands [anthropomorphism] is a tool that subverts the narcissistic self-portrait we so readily impose on our animal friends. Often as not, like a mirror, his films hold up to us seemingly familiar grotesqueries such as the vampire bat's peaked snout, ceaselessly quivering in the throes of a lascivious frenzy, as if to say, "Identify with that!"

The film Les Assassins d'eau douce (Freshwater Assassins) ends in glorious, shameless anthropomorphism. After we've watched insects, crustaceans and other assorted water bugs engage in acts such as "injecting gastric juice and swallowing the pulp of dissolved tissue" of their neighbors—to the music of Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington and Gene Krupa—the narrator tells us that "In all these murders, one is overwhelmed by the supplicating gestures of the victims; one can imagine their cries."

Science Is Fiction closes with a 1986 interview that shows the filmmaker as a witty old cuss. It is filled with hilarious anecdotes. Unfortunately, many of these are already familiar, since other contributors to Science Is Fiction, drawing from Painlevé's own writing, have, in effect, scooped him.

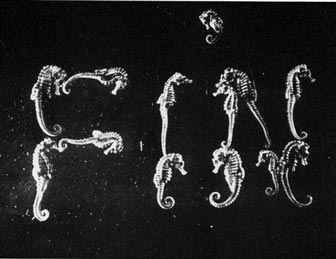

From Science Is Fiction

No one scoops Painlevé's statement that "scientific film requires study and instruction; it is not only a tool, but a grammar and an art." But Rugoff's essay helps explain what Painlevé meant. Film is a medium in which movement is central—and in this sense it is like life itself. In Painlevé's films, Rugoff says, "We glimpse a world in which movement is the universal alphabet. . . . It is no coincidence that Painlevé typically ended his films with a witty flourish in which the live organisms we have just been watching rearrange themselves into the shape of static letters spelling 'Fin.' When movement ceases, in other words, the show is over."—William J. Cannon, Raney Street Productions, Carolina Biological, Burlington, North Carolina

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.