Nanoviews: Inventing Modern America, Envisioning Science and more

By

Short takes on nine books

Short takes on nine books

DOI: 10.1511/2002.27.0

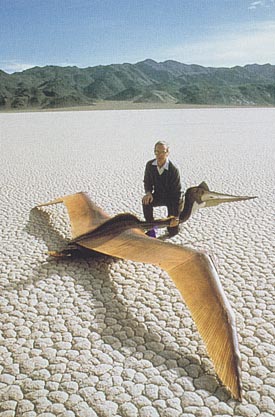

The lives of many of this country's most successful innovators provide ample fodder for David E. Brown's Inventing Modern America: From the Microwave to the Mouse (MIT Press, $29.95). Attractively illustrated and aimed squarely for a place on the coffee table, this volume offers brief essays on American inventors and their inventions. Some of the names are well known--Henry Ford, Buckminster Fuller, Robert Goddard and George Washington Carver, to name a few. Others are more obscure, including Wilson Greatbatch (who built the first pacemaker), Ashok Gadgil (who engineered a system to purify water with ultraviolet light) and Sally Fox (who breeds naturally colored cotton as an environmentally friendly alternative). Although the desire to aid humankind is a common motivation for many of these inventors, necessity too is mother to some of their brainchildren. Paul MacCready, for example (shown below holding a mechanical pterodactyl), pioneered human and solar-powered flight only after being saddled with a large business debt, which spurred him to vie for the $100,000 prize offered for the first human-powered plane to complete a figure-8course.

From Inventing Modern America: From the Microwave to the Mouse

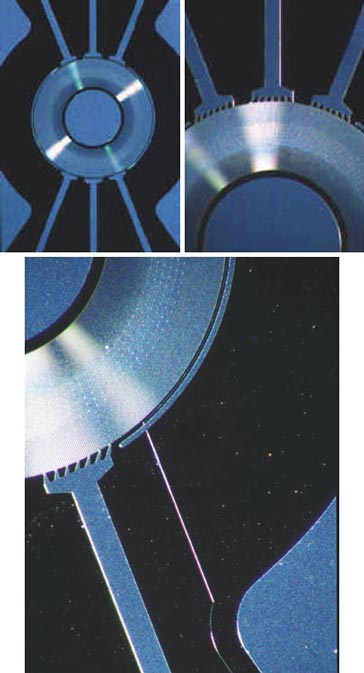

If you're a practicing scientist, photographer Felice Frankel would like "to teach you to see." Actually she wishes to nudge you to imagine, create and present better scientific images to convey the ideas, information, beauty and wonder of your work to colleagues and to broader audiences. In Envisioning Science: The Design and Craft of the Science Image (MIT Press, $55), Frankel offers a toolset for the task and reveals the technique lying behind the stunning images she captures through the microscope (such as these stereomicroscope images of a microdevice, which show how an off-center framing can be more effective). Dispensing advice on matters practical, aesthetic and ethical, Frankel urges rigor and full disclosure in the digital alteration of images and urges scientists to pay attention to design and taste in using tools such as presentation software: "Crawling words and animated colored sentences or striped fuchsia backgrounds," she notes, ". . . will never replace good solid science."

From Envisioning Science: The Design and Craft of the Science Image

As you take out some leftover lasagna from the refrigerator, you notice that the aluminum foil covering the stainless steel pan holding the lasagna has been perforated with tiny holes where it touched the food. Is there something sinister going on? The man who knows the answer to such kitchen mysteries is retired chemist Robert L. Wolke, who writes the "Food 101" column in the Washington Post. Wolke and his editors have collected some of his best essays and presented them in a Q&A format in What Einstein Told His Cook (Norton, $25.95), along with some recipes. Among other things, you'll learn why French butter is tastier than American butter (more fat), why potato-chip bags are always opaque (ultraviolet light makes the fats rancid), and whether belching contributes to global warming (yes, but not significantly). And what about the lasagna mystery? It turns out that your leftover lasagna and its container constitute an electric battery: The tomato sauce acts as a conductor between the aluminum foil and the steel pan holding the lasagna. An electrolytic reaction dissolves the foil as the steel pan robs it of its electrons, oxidizing the aluminum. Wolke is Martha Stewart with a Ph.D.

From What Einstein Told His Cook

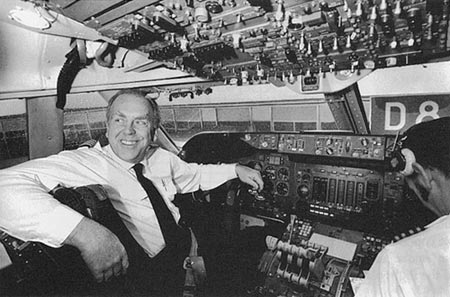

Ever have a hankering to get behind the wheel of a jumbo jet--or just curiosity about what goes on up there? Bob Buck's North Star over My Shoulder (Simon & Schuster, $26) will drop you into the cockpit with one of the world's most accomplished commercial aviators. From his early days in biplanes, setting the junior transcontinental record at age 16 in 1930, to his retirement as a TWA 747 pilot in 1974, Buck's account of a life up in the air proves him to be not just an able pilot but a gifted writer as well. Visit places as diverse as Paris and Marrakech, meet people ranging from Pa Bowyer (his first instructor) to Howard Hughes, and learn the nuances of airplanes as storied as the Ford Trimotor and a thunderstorm-chasing B-17. And best of all, visit or revisit a time when flying and fliers were larger than life.

From North Star over My Shoulder

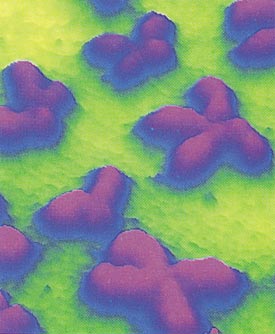

Two new books on the world's coral reefs give ample demonstration of the claim that these underwater ecosystems rival the tropical rain forests in biodiversity. Outrageous in color and form, the beasts that live in and around the reefs are captured in photographs on the pages of Reef Life (Firefly Books, $24.95), a field guide by Andrea and Antonella Ferrari. This portable guide depicts hundreds of reef species--fishes, nudibranchs (sea slugs), sea urchins, sponges, crinoids, giant clams (right) and others--and provides brief descriptions of their range, habitat, size and behavior. The global distribution of these remarkable ecosystems is mapped in an ambitious new work, the World Atlas of Coral Reefs (University of California Press, $55), by Mark D. Spalding, Corinna Ravilious and Edmund P. Green. Filled with colorful maps and photographs, the atlas also integrates short essays on each of more than 50 reef systems distributed throughout the tropical waters of the globe. The world is a richer place because coral reefs exist, but these ecosystems are in grave danger. Many are quite unhealthy, in part due to human activity, but also due to disease and rising sea-surface temperatures. The elkhorn coral (far right), for example, has been devastated by disease in the Caribbean. Unless the global trend is reversed, these two books may someday serve as colorful epitaphs for what once was.

From World Atlas of Coral Reefs

From Reef Life

The fanfare surrounding the sequencing of the human genome hasn't died down quite yet. The journal Nature, which published one of the two analyses of the sequence in February 2001, prolongs the merriment with The Human Genome (Palgrave, $30). This heavily illustrated volume, edited by Carina Dennis and Richard Gallagher, is slimmer than the issue of Nature it memorializes. The key paper from the international consortium and the handful of opinion pieces that accompanied it are republished here and supplemented by colorful introductory chapters with eye-catching illustrations and a profusion of sidebars. These chapters, which set the scene and establish the significance of the project for a general readership, reinforce the import of the genome, address the methods used to sequence it, survey the genomic landscape and discuss the potentially grave impact of this information on society. Those who dread the yellowing of their February 15, 2001, issue of Nature may value this book (it is printed on sturdier paper and hardbound) but miss the articles that are absent here--more than a dozen papers analyzing the sequence and 10 other experimental papers.

From The Human Genome

The National Audubon Society's informative Guide to Marine Mammals of the World (Knopf, $26.95) gives an overview of the various families of marine mammals from polar bears, otters, walruses and seals to whales, dolphins and porpoises, and describes for each individual species its physical characteristics (including measurements and life span), behavior, reproductive habits, range and habitat, food and foraging tactics, and conservation status. Identification of some species is almost impossible, and others are found in environments that are almost inaccessible. Even with the aid of the splendid photographs and paintings that are included, identifying a species in water is very difficult, as the book warns and I can attest. A group of dolphins who crossed my path recently when I was on a research cruise off the Carolinas were in my range of vision for only a few minutes, and at the surface only about 10 percent of that time. I think they were Atlantic spotted dolphins (far left), but they could have been pantropical spotted dolphins (left)--I'll never know for sure.

Besides that Benjamin we all know from elementary school--Franklin--there was another great, but less familiar scientist Benjamin in the early days of the Republic. The subject of Charles A. Cerami's biography Benjamin Banneker: Surveyor, Astronomer, Publisher, Patriot (Wiley, $24.95), was a Maryland tobacco farmer, the grandson of an enslaved African prince who had been freed so that he could marry his milkmaid owner, who had herself come over from England as an indentured servant.On the basis of observations with crude instruments of the day, Banneker speculated on the existence of binary stars and "extrasolar planets" elsewhere in the universe that might be capable of supporting intelligent life. Cerami suggests that his subject also anticipated Einstein's theories on light and relativity. His case for the astronomer's brilliance is slow to develop but nonetheless fascinating. Here is a rare glimpse at what a free, highly intelligent and creative African-American had to go through just to get by in the Colonies, from avoiding being kidnapped and sold into slavery by white gangs to mixing it up in print with Thomas "All Men Are Created Equal" Jefferson, who owned human beings of Banneker's complexion.

From Guide to Marine Mammals of the World

From Guide to Marine Mammals of the World

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.