Nanoviews: Engines of Tomorrow, The Bit and the Pendulum, and more . . .

By The Editors

Short takes on nine books.

Short takes on nine books.

DOI: 10.1511/2000.29.0

The "engines" of Robert Buderi's Engines of Tomorrow: How the World's Best Companies Are Using Their Research Labs to Win the Future (Simon & Schuster, $27.50) are intellectual, and both the historical narrative and analysis are gripping. This wonderful story of research in an industrial context is, itself, the fruit of a prodigious amount of research. Buderi cheers the 90s' refocusing of resources, and he allows that equilibrium has not yet been reached and that the future of fundamental research may still be bright.

According to Tom Siegfried’s The Bit and the Pendulum: How the New Physics of Information Is Revolutionizing Science (Wiley, $27.95), the computer has become the same sort of "superparadigm" for our understanding of the physical world that clockwork was to Newton. The conceptual payoff is exciting. The words and tone will give a teenager who has yet to take a first physics course some sense of quantum computing.

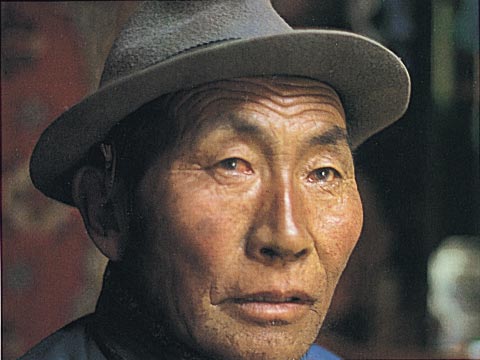

From Gobi: Tracking the Desert

In Gobi: Tracking the Desert (Yale University Press, $24.95), John Man mixes the travel-writing spirit of Peter Matthiessen and Bruce Chatwin with his own wry sense of humor to take us on a delightful ramble through the Gobi desert. Find out what a Mongolian does when he looks after his horse, study signs of the snow leopard, explore the Nine Pots of the Sacred Mother and come to appreciate a wilderness that is fading fast.

Does evolution have a direction? Does human history have meaning? These classic questions have troubled more than one wretched undergraduate who finds himself without a date on a Saturday night. Now in Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny (Pantheon, $27.50), journalist Robert Wright tackles these chestnuts with the principles of game theory. Since both evolution and human history can be described as "non–zero-sum" games, in which there can be a winner without a loser, the net result in an exchange between "players" is frequently positive. In the long run, the net positives add up to give both direction and meaning, according to Wright. The book is a nice argument against the party-line belief among biologists that the history of evolution has neither produced greater complexity nor shown direction. Wright's ideas about the meaning of life and the notion of "God" are interesting—but be forewarned, Wright's answers might not soothe the existential despair of the lonely college sophomore.

I've always wanted to have a twin brother. Among the perks, I imagined, would be the opportunity to see oneself from the outside, as others might. For all the twin "wannabes" out there, psychologist Nancy L. Segal explores what it means to be a twin in Entwined Lives: Twins and What They Tell Us About Human Behavior (new in paperback from Penguin/Plume, $16). The science is all here, but so is a deep sense of what twins mean to each other. Segal also serves up an assortment of eerie similarities between identical twins reared apart, including two brothers who flushed the toilet before and after using it and who both enjoyed sneezing loudly in crowded elevators. Perhaps one drawback to being a twin is that you just might realize how annoying you are to others.

In Absolute Zero and The Conquest of Cold (Houghton Mifflin, $24), Tom Shachtman explores the science and history of humankind's increasing control of cold. He opens with the remarkable story of Cornelis Drebbel (who billed himself as a magician), who "air-conditioned" Westminster Abbey on a hot day in the summer of 1620 for the pleasure of King James I of England. Throughout the book, Shachtman successfully intertwines similarly curious tales surrounding the development of cold technology with accounts of the historical and social conditions of the time. His treatment of the science involved is not as reliably successful and seems to deteriorate as he moves closer to the modern era of cooling technology. However, the book does a fine job of placing the process of science in a clear social context.

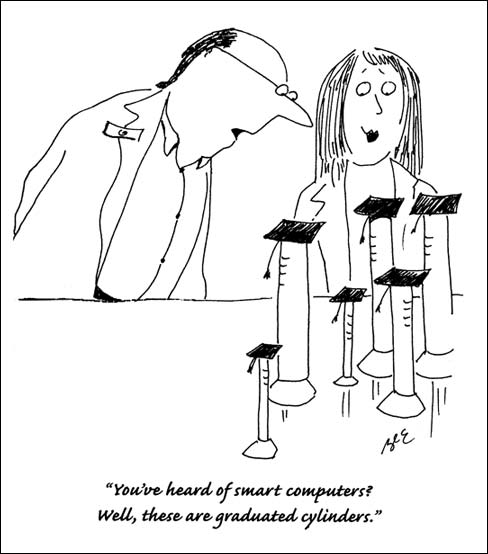

From Science of Little Round Things

Trained in entomology, Benita L. Epstein doodled in her lab notebooks for two decades before her cartoons began appearing in magazines and newspapers. Readers who have enjoyed her work since her first appearance in these pages in 1992 will be pleased to find that McFarland & Company has published a third collection under the title of that cartoon, Science of Little Round Things ($22.50). As an extra treat Epstein presents a few of the direct-from-life lab sketches that inspired cartoons such as the one below.

In The Relationship Code: Deciphering Genetic and Social Influences on Adolescent Development (Harvard University Press, $55), David Reiss and colleagues propose that patterns of family relations—between siblings, mother and child or father and child—actually function as a kind of code that influences genetic DNA by altering the expression of genes that control behavioral traits. What makes the work fascinating is the authors’ patient and thorough explanation of the research methods used to consider the influences, both genetic and psychosocial, on adolescent development.

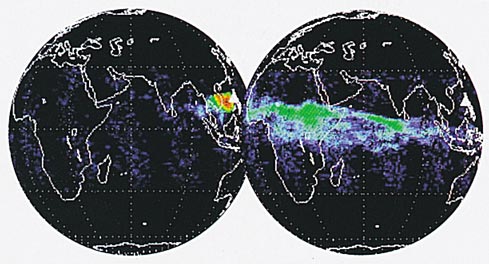

From The Climate Revealed

Building Planet Earth: Five Billion Years of Earth History and The Climate Revealed (both from Cambridge University Press at $39.95 each), sized for the coffee table, offer visually rich forays into earth science. The former, by Peter Cattermole, has the look and feel of an introductory geology textbook, but the latter, by William J. Burroughs, provides somewhat lighter fare; it is studded with stunning, magazine-quality photographs and offers a new topic with literally every turn of the page. The satellite images below (from The Climate Revealed) show how the dust cloud from the eruption of Mount Pinatubo in 1991 was swept around the world in just 10 days by winds in the stratosphere.

Nanoviewers: Samuel J. Petuchowski, Rosalind Reid, Linda Schmalbeck, David Schneider, David Schoonmaker, Rebecca Slotnick,

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.