This Article From Issue

November-December 2008

Volume 96, Number 6

Page 518

DOI: 10.1511/2008.75.518

MUSICOPHILIA: Tales of Music and the Brain. Oliver Sacks. xiv + 381 pp. Alfred A. Knopf, 2008. $26.

Music and the brain are both endlessly fascinating subjects, and as a neuroscientist specializing in auditory learning and memory, I find them especially intriguing. So I had high expectations of Musicophilia, the latest offering from neurologist and prolific author Oliver Sacks. And I confess to feeling a little guilty reporting that my reactions to the book are mixed.

Dr. Sacks comes across as a kind, compassionate, careful observer, who is concerned above all with providing sensitive and humane treatment for his patients. Many of them have symptoms that cannot be relieved by drugs or other therapies. Often he can offer nothing more than reassurance, as when he comforts a woman by explaining that her constant musical hallucinations have a real, physiological basis; she copes better knowing that she is neither crazy nor unique.

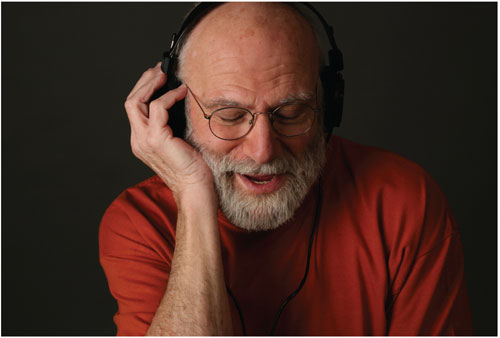

Sacks himself is the best part of Musicophilia. He richly documents his own life in the book and reveals highly personal experiences. The photograph of him on the cover of the book—which shows him wearing headphones, eyes closed, clearly enchanted as he listens to Alfred Brendel perform Beethoven's Pathétique Sonata—makes a positive impression that is borne out by the contents of the book. Sacks's voice throughout is steady and erudite but never pontifical. He is neither self-conscious nor self-promoting. Readers might easily imagine that they are listening to Uncle Oliver recount weird and wonderful "tales of music and the brain" around a campfire.

The preface gives a good idea of what the book will deliver. In it Sacks explains that he wants to convey the insights gleaned from the "enormous and rapidly growing body of work on the neural underpinnings of musical perception and imagery, and the complex and often bizarre disorders to which these are prone." He also stresses the importance of "the simple art of observation" and "the richness of the human context." He wants to combine "observation and description with the latest in technology," he says, and to imaginatively enter into the experience of his patients and subjects. The reader can see that Sacks, who has been practicing neurology for 40 years, is torn between the "old-fashioned" path of observation and the newfangled, high-tech approach: He knows that he needs to take heed of the latter, but his heart lies with the former.

The book consists mainly of detailed descriptions of cases, most of them involving patients whom Sacks has seen in his practice. Brief discussions of contemporary neuroscientific reports are sprinkled liberally throughout the text.

The book's 29 chapters are divided into four main sections by topic. Part I, "Haunted by Music," begins with the strange case of Tony Cicoria, a nonmusical, middle-aged surgeon who was consumed by a love of music after being hit by lightning. He suddenly began to crave listening to piano music, which he had never cared for in the past. He started to play the piano and then to compose music, which arose spontaneously in his mind in a "torrent" of notes. How could this happen? Was the cause psychological? (He had had a near-death experience when the lightning struck him.) Or was it the direct result of a change in the auditory regions of his cerebral cortex? Electroencephalography (EEG) showed his brain waves to be normal in the mid-1990s, just after his trauma and subsequent "conversion" to music. There are now more sensitive tests, but Cicoria has declined to undergo them; he does not want to delve into the causes of his musicality. What a shame!

Switching from musicophilia to musicophobia, Sacks devotes most of the rest of the book's first section to music that people don't want in their heads—hallucinatory music, for example, or a jingle that repeats itself endlessly. In one particularly poignant passage, he describes a boy of nine who hears one song after another without cease. This music is sometimes unbearably loud, causing what his mother refers to as "acoustic agony." The child screams in pain and in frustration. Drugs that reduce cortical excitability help, but only a little—respite from the internal music is very brief.

Part II, "A Range of Musicality," covers a wider variety of topics, but unfortunately, some of the chapters offer little or nothing that is new. For example, chapter 13, which is five pages long, merely notes that the blind often have better hearing than the sighted. The most interesting chapters are those that present the strangest cases. Chapter 8 is about "amusia," an inability to hear sounds as music, and "dysharmonia," a highly specific impairment of the ability to hear harmony, with the ability to understand melody left intact. Such specific "dissociations" are found throughout the cases Sacks recounts.

To Sacks's credit, part III, "Memory, Movement and Music," brings us into the underappreciated realm of music therapy. Chapter 16 explains how "melodic intonation therapy" is being used to help expressive aphasic patients (those unable to express their thoughts verbally following a stroke or other cerebral incident) once again become capable of fluent speech. In chapter 20, Sacks demonstrates the near-miraculous power of music to animate Parkinson's patients and other people with severe movement disorders, even those who are frozen into odd postures. Scientists cannot yet explain how music achieves this effect.

Musicophilia closes with several chapters on "Emotion, Identity and Music." Sacks is perhaps at his best dealing with this material. He enthuses about the special musicality of children and adults who have Williams syndrome and gives an intriguing summary of evidence that frontotemporal dementia may "release" artistic abilities. He is particularly insightful and inspiring in the final chapter, "Music and Identity: Dementia and Music Therapy." Here Sacks emphasizes his belief, with which I am in wholehearted agreement, that humans are a "musical species." He could have made his case, which relies on the universality of music, even stronger by bringing in evidence that neonates, and even third-trimester fetuses, have the ability to perceive music.

In his closing thoughts, Sacks speaks eloquently of the preservation of musical ability and music appreciation in patients with advanced Alzheimer's disease:

Music is part of being human, and there is no human culture in which it is not highly developed and esteemed. Its very ubiquity may cause it to be trivialized in daily life: we switch on a radio, switch it off, hum a tune, tap our feet, find the words of an old song going through our minds, and think nothing of it. But to those who are lost in dementia, the situation is different. Music is no luxury to them, but a necessity, and can have a power beyond anything else to restore them to themselves, and to others, at least for a while.

To readers who are unfamiliar with neuroscience and music behavior, Musicophilia may be something of a revelation. But the book will not satisfy those seeking the causes and implications of the phenomena Sacks describes.

For one thing, Sacks appears to be more at ease discussing patients than discussing experiments. And he tends to be rather uncritical in accepting scientific findings and theories.

There are a number of examples of this tendency, but I will describe in detail just one. In considering why musical hallucinations are so vivid, Sacks cites the 1967 monograph of the late Jerzy Konorski, a brilliant, currently underappreciated behavioral neuroscientist. Konorski's thesis is that hallucinations are caused by connections going from the sensory regions of the brain to the sense organs (so-called "retro" or "descending" connections). He hypothesizes that hallucinations are normally inhibited by sensory experiences but that when sensory stimulation falls below a certain level, the "retro" fibers act on the sense organs to produce "virtual" experiences that are as vivid as real ones.

Sacks swallows this theory whole, stating that although evidence of such connections was scant in the 1960s, it is now overwhelming. In fact, the descending connections of the auditory system to the cochlea were well known even in the 1960s. However, the existence of retro connections cannot validate a particular theory about their function.

The explanation that a deficiency of input from the sense organs will facilitate a backflow "now seems obvious, almost tautological," Sacks says. But Konorski's schema is light-years away from being self-evident. It fails to explain why hallucinations can occur without any strong sensory deprivation. Nor does it shed any light on why the brain, which already possesses the hallucinatory material, needs to send extremely detailed hallucinatory scenes to the retina or cochlea, where they must be precisely reconstituted into a "real" sensory experience and returned to the sensory cortices. After all, the brain could produce the vivid images itself, as it does in the case of phantom limb sensations.

It's true that the causes of music-brain oddities remain poorly understood. However, Sacks could have done more to draw out some of the implications of the careful observations that he and other neurologists have made and of the treatments that have been successful. For example, he might have noted that the many specific dissociations among components of music comprehension, such as loss of the ability to perceive harmony but not melody, indicate that there is no music center in the brain. Because many people who read the book are likely to believe in the brain localization of all mental functions, this was a missed educational opportunity.

Another conclusion one could draw is that there seem to be no "cures" for neurological problems involving music. A drug can alleviate a symptom in one patient and aggravate it in another, or can have both positive and negative effects in the same patient. Treatments mentioned seem to be almost exclusively antiepileptic medications, which "damp down" the excitability of the brain in general; their effectiveness varies widely.

Finally, in many of the cases described here the patient with music-brain symptoms is reported to have "normal" EEG results. Although Sacks recognizes the existence of new technologies, among them far more sensitive ways to analyze brain waves than the standard neurological EEG test, he does not call for their use. In fact, although he exhibits the greatest compassion for patients, he conveys no sense of urgency about the pursuit of new avenues in the diagnosis and treatment of music-brain disorders. This absence echoes the book's preface, in which Sacks expresses fear that "the simple art of observation may be lost" if we rely too much on new technologies. He does call for both approaches, though, and we can only hope that the neurological community will respond.

Norman M. Weinberger is a research professor in the Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, and a fellow of the Center for the Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, at the University of California, Irvine.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.