Why Do Virtual Meetings Feel So Weird?

By Elizabeth L Keating

Even as online meetings become more common, they can’t always capture the nuances of nonverbal communication and in-person interactions.

Even as online meetings become more common, they can’t always capture the nuances of nonverbal communication and in-person interactions.

It’s morning in Houston, Texas, for Jeremy and his team of engineers, and nearly evening in a small town north of Bucharest, Romania, for Costa and his team when they all sit down for a phone meeting in 2011. (All names of interviewees have been changed to protect their privacy.)

They’ve gotten to the fourth item on their meeting agenda when Jeremy realizes the team in Houston has been operating with the wrong assumption about the number of pumps in the petroleum plant design they are working on.

Who else knows about this?” Jeremy asks Steve, who sits beside him.

“Good question,” Steve says.

As an anthropologist observing them, I realize it’s a big, amorphous question. There’s way too much ambiguity about who knows what and what information is located where. The gaps have led to at least one serious misunderstanding.

Before 2008, everyone on this team shared the same office. Drawings were kept in the squad room, and employees came and went to check the same version of the design. Knowing the number of pumps would have been a no-brainer. Back then, information flowed easily around the office, and when new engineers joined the team, they learned a lot simply from watching things in the normal course of a day.

Now things are different.

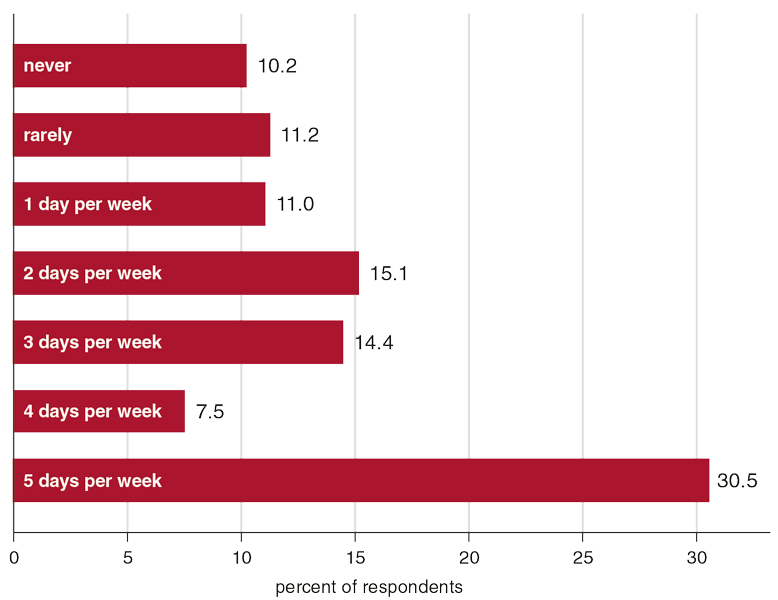

The COVID-19 pandemic has meant that many more people are, like these engineers, working on complex tasks through computer screens. In 2015, nearly a quarter of respondents to a survey by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported working from home at least some of the time. As of May 2020, that number nearly doubled, with 42 percent of U.S. employees working from home full time, according to a study led by economist Nicholas Bloom of the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. In Europe, where strict lockdowns have closed many offices and businesses, the European Commission Joint Research Centre found that half of those now working from home had no previous experience with teleworking.

Switched Design/Shutterstock.

How-to guides for remote video communication tend to focus on technical issues, appearance (such as a person’s dress and hair), lighting, the backdrop, and how to manage interruptions and peculiarities within “home” space—the dog barking or a child knocking at the office door. But there is much more to say about this kind of communication.

As a linguistic anthropologist, I’ve been interested in technologically mediated interaction ever since the webcam first became widely available in the late 1990s; I wrote a book about it in 2016. I can see why people today are remarking, with some irony, that in spite of the enormous promises of technology to keep people connected while staying safely out of harm’s way, they are experiencing the unexpected disappointments of isolation, exhaustion, feeling out of the loop, and a lack of community.

Jeremy and Costa were part of my most recent study on remote communication. I conducted research on their team while they designed state-of-the-art petroleum processing plants from remote locations between 2008 and 2011, and again in 2016 and 2017. Although some members of this project were in a shared office, the expertise on the team was distributed across 30 to 50 people on at least two continents.

Like many people today, Jeremy and Costa depended on email to send documents and to critique and assign tasks. They had weekly conference calls—both audio calls to discuss action items and video calls to review and make changes on the model they were creating.

Before I met the engineers and got to know their work lives, the managers of these companies told me that the financial gains they had anticipated from their online international collaboration had not come to fruition, in part because of the increased managerial costs of a far-flung team.

But what else was at play? I had earlier heard many engineers describe culture as a factor that could make or break virtual engineering teams—vocabulary, along with unstated assumptions and procedures, can vary from place to place. This problem is all too often underestimated.

From things the engineers said in our introductory meetings, I assumed that these cultural differences, along with difficult logistics such as time zones, would be what made their work so challenging, and would be key to answering Jeremy’s somewhat exasperated question, “Why don’t they just understand what to do?” But I was off the mark.

It turned out that a big contributor to frustration and having to do things over again was the loss of two forms of knowledge critical to any team and to any interaction: nonverbal communication and peripheral participation. Most people hardly give a thought to these kinds of communication—they have only recently become hot topics of investigation in online work worlds.

Those of us working from home now are experiencing quite drastic changes in what the sociologist Erving Goffman described so aptly in his books and articles of the 1960s as “focused interaction.”

What Goffman meant by that was not only the exchange of words in an interaction but also the crucial role of sight. Small glances were not insignificant details to him. As he put it, each of us notices how we are being experienced by other people. Further, each person can be observed noticing that they are being experienced in a certain way by others, and each person “can see that he has been seen seeing this.”

The ability to see people and to observe them observing us during work builds a framework for a lot of important parts of teamwork.

With this tongue twister, Goffman is getting at the dynamic, reciprocal way humans keep each other in view. We use what we see to decide how to react and what to do next, and even to predict someone’s future behavior, and this view can include quite a few people. The way we focus on and acknowledge one another has a certain elegant economy to it; it happens while we are paying attention to other things.

The ability to see people and to observe them observing us during work builds a framework for a lot of important parts of teamwork. It helps us establish trust, gain commitment, confirm understanding and consensus, and understand emotional states. Goffman had an anthropologist’s eye for the details of human interaction.

Most people realize that in the transition from an office to an online remote setting, we are losing critical information about the very people we depend on to get the job done. This reduced form of interaction contributes to the perception of remote work as less satisfying and more exhausting. Even though we often have good visual information about at least some people’s faces with today’s technological sophistication, we don’t have as much information as we are used to from in-person interactions.

In Goffman’s terms, we lose the ability to observe others observing us, because we often don’t know where their gaze is directed. (They’re looking at their screens, not us.)

The knowledge that is transmitted by our bodies—often referred to as nonverbal communication—has rarely been taken seriously. There’s the name of it, for one thing: How serious can we be about understanding something when we label it by what it is not? There are no departments in universities dedicated to nonverbal or embodied communication, and few books on communication consider it beyond a cursory discussion.

We need a rich vocabulary for describing nonverbal communication akin to what linguists use when discussing verbal output. Yet anthropologist and scholar of body language Ray Birdwhistell, who in the 1940s and 1950s was one of the first to seriously study nonverbal behavior, estimated that “facial expression, gestures, posture and gait, and visible arm and other body movements” make up about two-thirds of the social meaning of a conversation.

Bodies talking and listening in conversation are highly expressive. We know this. They give off signals about emotional state, attitude, stance on a topic, whether people are confused or following along, whether they are excited or getting bored, how they are responding to our idea, and many other things that make it possible to work together. But, ironically, many online guides advise us to subdue our gestures or even recommend keeping the upper body motionless. In many cases, people turn their cameras off or use audio-only technologies.

One day I was observing an audio conference call between the engineers in Houston and those in Romania. The topic was a change in design of a support for platforms. They had all come to an apparent agreement.

“YES!” Jeremy had clearly voiced.

“Maybe—” Costa started with an idea.

“Yes, but—” Jeremy stepped in.

Costa kept talking while Jeremy kept trying to finish.

“He’s difficult to interrupt!” Bob in Houston said, laughing. He then intervened on Jeremy’s behalf. “Hold on just a second. Jeremy was trying to say something.”

Nicholas Bloom, Stanford University

Many online workers are now experiencing how people start to talk at the same time, then apologize, then start to talk at the same time again. People hesitate to speak because they don’t want to get into this awkward dance.

Most people have never thought about taking turns or how they use eye gaze and head nodding, their own or other people’s, to facilitate easy conversations. Those who study the split-second timing and rhythmic coordination of turn taking, as conversation analysts do, describe how these split-second signals work—the ones Goffman was talking about, from gaze to the inclination of the body. People even notice if someone takes a certain kind of in-breath when they want to bid for a turn without interrupting someone else. These are all signals that, despite our high-resolution screens, are not yet easy to pick up online.

The engineers, being engineers, told me they were so frustrated by their constant failure to coordinate the “simple” act of turn taking in their conversations, a failure they’d never experienced before, that they wanted to design a special turn-taking button—a kind of technological version of a baton.

A second critical loss the engineers experienced was what linguistic anthropologists call peripheral participation. This term refers to the process by which newcomers become acclimated to existing communities of practice, an idea that was first developed by those studying theories of learning.

The term peripheral indicates diminished status (like the “non” in nonverbal), but it’s actually one of the most significant aspects of a professional environment. Peripheral participation is especially important in mentoring and in fostering inclusivity, as well as in ensuring members of a team are on the same page.

In one international institute where I was a researcher, the room where we sought out coffee, tea, and the odd slice of birthday cake was renamed the Tiny Conference Room (and a sign was put on the door announcing this change). The new name was an acknowledgment of the many important exchanges that went on there, including the one-on-one intense mentoring that characterizes professional learning, although people were ostensibly “just” getting coffee.

As newcomers to a profession move from being peripheral participants to becoming full participants, they develop “who knows what” directories of knowledge. But after moving to work environments dependent on online communication, the engineers had to “chase knowledge,” as they put it.

Engineers who worked remotely with the engineers in the United States said, “We miss the hallway stuff.” Andrei told me that when he spent time in Houston, he was able to build a mental map of “who knows what.” When he got back to Romania, the map quickly became outdated.

In the current pandemic, efforts at fostering worker interactions have to be reinvented. Many pre-COVID-19 offices were full of space for accidental meetings and rich not only in linguistic but also in sensory and contextual cues. Workers have long taken these for granted. It’s time to recognize them, not just by their absence but by acknowledging their importance.

I’m an anthropologist who studies human interactions, not an IT developer, but I can see that there are academics and companies out there chasing technological solutions: Communication tools named after the Watercooler and Hallway are intended to facilitate peripheral participation, and enhanced video or virtual reality projections are designed to make people feel they are really “there” with one another.

Some developers have proposed a pressure-sensitive chair to record how we move our bodies, linking these movements to signs of interest or disinterest. Other projects have shown that avatars that use gestures improve engagement and communication in work collaborations—even when those gestures are only accidentally triggered by the user.

Many of these developments acknowledge that technologies won’t achieve what we want them to achieve unless we keep the human lessons in mind. Communication, after all, is about people—not just our words but our gestures, feelings, and mental maps. But there’s still a long way to go to incorporate all these developments into more fulfilling and effective virtual work.

This article was adapted from a version previously published in Sapiens, sapiens.org.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.