This Article From Issue

May-June 2000

Volume 88, Number 3

DOI: 10.1511/2000.23.0

The Eternal Darkness: A Personal History of Deep-Sea Exploration. Robert D. Ballard with Will Hively. 314 pp. Princeton University Press, 2000. $29.95.

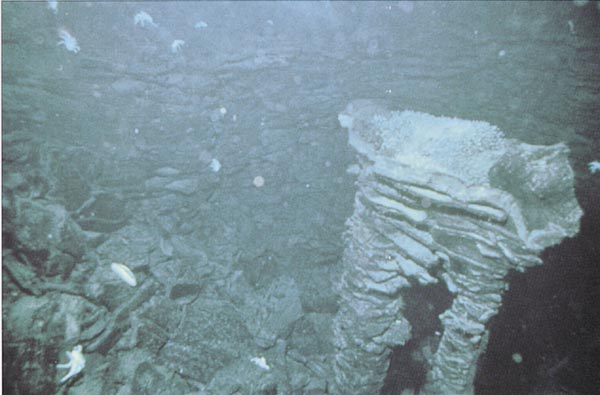

Robert Ballard is the father of a modern icon: the rust-draped prow of the sunken Titanic, which he and his crew located in 1985. This image anchored the highest-grossing film in Hollywood history. Ballard is also an eminent scientist—he led the 1977 expedition that discovered deep-sea hydrothermal vents and their exotic fauna, the most profound oceanographic find of the 20th century. After the death of Jacques Cousteau, he became the world's most famous oceanographer. Judged from his academic resume, his previous books and his TV appearances, Ballard seems to be a natural storyteller with a flair for drama. Who better to write the history of deep-sea exploration?

From The Eternal Darkness

The Eternal Darkness joins a recent tsunami of popular books about the oceans, including scientific treatments such as The Universe Below by William J. Broad, Deep Atlantic by Richard Ellis, The Octopus's Garden (reissued as Deep-Sea Journeys) by Cindy Lee Van Dover and The Restless Sea by Robert Kunzig (as well as Sebastian Junger's best-selling adventure tale, The Perfect Storm). Yet there is very little redundancy among these contributions. Each gives its own updated perspective, Rashomon-style, to the oft-told tales of past forays into the deep oceans. And each stakes out its own turf in describing present-day ocean research.

The history of deep-sea exploration has followed the classic model: A strong-willed leader finds the funding, assembles the crew and oversees the engineering. This role has been played in turn by William Beebe and Otis Barton, Auguste and Jacques Piccard, Cousteau—all of whom are introduced in this book—and now Ballard. Only such a visionary can battle bureaucracies, reinvent a mission when it is stymied and look ahead to the next challenge as each hurdle is surmounted.

Ballard begins with three chapters of brief "prequel" sketches of his 20th-century predecessors. Their pioneering exploits are re-created as action yarns interwoven with perspectives on their historic significance. The nickname for one of these episodes—Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh's 1960 descent to the deepest point in the world, the Challenger Deep of the Mariana Trench in the western Pacific—might have made a better choice for Ballard's title: "The Big Dive." Darkness is really a chronology of "big dives," from Beebe and Barton's "Half Mile Down" in 1932 to Ballard's modern quests for ancient shipwrecks in depths that never could be searched before.

Ballard first enters the narrative in the third chapter, and in the fourth he begins to put the "personal" of the book's subtitle into his history. This qualifier is appropriate. The book is not a comprehensive, objective overview of the evolution of deep-sea exploration so much as a series of guided field trips, most of them sharing a porthole with Ballard. But the personal focus is valuable and fully justified, since Ballard has been the principal character in undersea exploration for the past two decades.

Historians of science will like the way that Ballard also notes the societal context that impeded, facilitated and directed deep-sea research. Key U.S. military mishaps in the Cold War in the early 1960s (losses of the nuclear submarines Thresher and Scorpion and of an H-bomb off Spain) prompted development of a new fleet of undersea vehicles—notably the submersible Alvin, still the workhorse of the fleet today. This technological boost truly began the modern era of sea-floor exploration. Scholars will also delight at his 60-page bibliography of technical literature, but most readers will be more interested in his brief "Note on Sources" that refers them to the classic original accounts of deep-sea dives in the words of their participants.

With numerous illustrations and a steady stream of exciting events, such as near-death experiences, Darkness begins in an engaging if not quite eloquent fashion. However, both the scope and the writing style change noticeably, picking up occasional overly technical passages, when Ballard enters the scene. After beginning with readable, magazine-style descriptions of early deep-sea vehicles, he suddenly plunges into minutiae of pipe welds and rescue chambers when describing the loss of the Thresher, the first wreck he found on the sea floor. When we join the first modern deep-sea research expedition, Project Famous (1973), evocative but undefined terms of geologic jargon such as "fault scarps," "lava flow fronts," "talus fans" and "pillow lavas" come at us full blast.

From The Eternal Darkness

Darkness seems to be a condensed version of Ballard's 1995 autobiography, Explorations. He and a new co-author (Will Hively, a contributing editor for Discover magazine) have rewritten accounts of Ballard's notable dives covered in Explorations: Project Famous to the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the momentous 1977 dive to the Galápagos Rift and subsequent similar missions, and, of course, the searches for the Titanic and other shipwrecks.

Darkness retains most of the meat about these journeys but shrinks and retools Ballard's life story to serve mainly as seasoning for the sea story. It greatly condenses Explorations's descriptions of the inside games Ballard and others had to play to obtain funding, to assemble research teams, and to build instruments, vehicles and institutions. These behind-the-scenes glimpses of human foibles and institutional jousting helped to dispel readers' naivete about the innocence and purity of scientific endeavor. Scientists and science groupies may have found the longer passages intriguing, as I did, but by slimming them down, Ballard has greatly broadened his potential readership. The result is a tighter focus on the science, technology and on-the-scene experience of deep-sea travel.

The compromise between mainstreaming the material and including worthy technical asides is shaky at times, however. Ballard bridges the transitions between dives with background on the origin of his missions and tools. These omniscient overviews lack the exciting verité of the dive sequences; fortunately, they are brief and do not impede the narrative flow. Yet this brevity sacrifices the first-person details that made Explorations interesting and obscures the important role that serendipity and personality play in dictating the course of science. The authors must have faced a tough choice: include such details and balloon the narrative to become like Explorations or drop the digressions altogether and lose some significant color commentary on the all-too-human side of this technological pursuit. They appear to have split the difference, and the results are mixed.

Darkness would have been a great opportunity to update Explorations with accounts of his latest accomplishments. In 1997, Ballard left the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution for a new venue, the Institute for Exploration. This organization, in Mystic, Connecticut, is more suited to his present-day exploratory and archaeological pursuits in the "world's largest museum," the deep sea. Ballard does add a final chapter arguing that unmanned vehicles will be the future of deep-sea research. But the book ends in 1993, the same year as Explorations, ostensibly because the technology had reached a plateau of maturity at this point.

A couple of his omissions are forgivable. He skips over his searches for sunken warships, which have been covered previously in books and television shows. His deadline perhaps did not permit inclusion of his 1999 discoveries of the world's oldest shipwrecks (off Israel) and of evidence of a great Black Sea inundation believed to have been Noah's flood. But he says little about one of his biggest and most commendable activities of the 1990s: the JASON Project, now in its 11th year of beaming his undersea images live and interactively to schoolchildren around the world. Of his recent activities at Mystic, he mentions only some new undersea vehicles under development, which were named by schoolkids in a contest in early 1999. Perhaps Mystic and the JASON Project are not milestones in the history of marine science, but they would have made enjoyable reading while bringing the documentation of Ballard's worthy activities into the 21st century.

Like deep space, to which it is often compared, the deep sea is a seemingly endless source of fascination for authors and readers alike. Yet, as Ballard and others constantly point out, we have seen more of the dark side of the moon than we have of the bottom of the ocean, and Neil Armstrong walked on the moon four years before scientists began systematic manned surveys of the deep-sea floor.

We also have had more, and more profound, writings about space than about the oceans. The two disciplines are now courting each other—serious scientists are now proposing that life on earth originated at deep sea vents and that similar life may have evolved on places such as Europa, the ocean moon of Jupiter. The science and the marketplace are ripe for a blockbuster analogous to Carl Sagan's Cosmos—one in which a scientific celebrity dramatizes how the oceans affect us all and are intimately linked to our past and future as a species. Robert Ballard, as both a respected scientist and a consummate educator and media figure, in many ways resembles an oceanographic Sagan. He has even fallen from grace among some of his colleagues, as Sagan did, because of his high public profile. Yet the oceanographic Cosmos remains to be written, by Ballard or someone else.

But enough about what this book might have been. It is still thoroughly absorbing and authoritative, imbued with the force of a great personality. For those whose appetite is whetted—and there will probably be many—it serves as an enjoyable popular portal to the literature of deep sea.

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.