Molecular Movie Stars

By Morgan Ryan

“It’s all about combining accuracy and aesthetics in the interest of transforming people’s understanding…”

“It’s all about combining accuracy and aesthetics in the interest of transforming people’s understanding…”

DOI: 10.1511/2009.80.382

In his popular 1993 book Taming the Atom, on the breaking revolution in visualizing the atomic realm, Hans Christian von Baeyer quoted Democritus: “I had rather discover one true explanation than be king of Persia.” An emerging community of crossover artists—scientists who animate—is living up to this philosophy in creating explanatory graphics. Their movies are data-driven, cinematic, scientifically sophisticated and entertaining. These new fantastic voyages cross molecular terrain, using the same software (and in one case, the same person) that churns out the enchanted special-effects environments in which Harry Potter and the Hobbit live. Hollywood-based Eric Keller is a well-known 3D instructor and special-effects animator who must budget his time between molecular projects and (his scientific colleagues pridefully note) next summer’s action blockbuster.

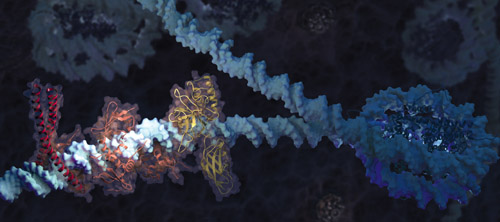

In this new genre of cinematic art, there is already a star walk. The admirers of Drew Berry, at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute in Australia, talk about him the way Cellini talked about Michelangelo. Janet Iwasa, now at Harvard, may have been the first scientific animation postdoc. The imaginitive Graham Johnson is now studying at the Scripps Research Institute, home of the great molecular portraitist David Goodsell (whose work appeared in the previous issue of American Scientist). Their productions can be seen at sites such as DNAtube.com, labaction.com, and molecularmovies.org, a showcase website curated by Gaël McGill, director of molecular visualization at Harvard Medical School, proprietor of the science-focused design shop Digizyme, creator of the image at left and author of the quote under the title above. McGill tells of working with a researcher to animate the activity of a fusion protein, after which his delighted collaborator reported that the process of translating data into animation had taught him new ways of studying the protein. “Visualization is not necessarily the end of the process,” says McGill. “It can inform discovery.”

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.