This Article From Issue

January-February 1998

Volume 86, Number 1

DOI: 10.1511/1998.17.0

Mirrors in Mind. Richard Gregory. 302 pp. W. H. Freeman, 1997. $26.95.

I first visited the Exploratorium in San Francisco in 1970, and I had a great time. Now there are Exploratorium-like places that provide hands-on experiences of the physical world and of perceptual phenomena in Chicago, Toronto, Durham, North Carolina and many other places, including England, where Richard Gregory founded the Exploratory, which helps explain why things appear as they do. No formal training is needed to enjoy these wonderful demonstrations. Gregory's Mirrors in Mind is an extension of his Exploratory. He has wondered about perception and light and seeing, and thus also necessarily about mirrors and reflection, for many years. This book gathers his many musings about mirrors and organizes what he has learned about what others have thought about his same questions.

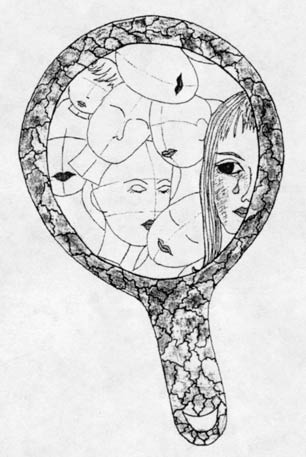

From Mirrors in the Mind.

Mirrors introduce ambiguity. Suppose that you see a speck of dirt on your friend's cheek and point this out by touching your left cheek. In response, does she rub her left cheek or her right cheek? And which did you intend? You could have reported as if you were a mirror, which would mean that her right cheek is smudged, or as if it were your own cheek, which would mean that her left cheek is smudged, and she could infer one or the other intent. In an informal survey, I found that about half of the people with whom I tried this inferred one cheek and half inferred the other. High or low on the cheek is not confusing, which means that the left-right problem is not just one of communication. Is this confusion because we are bilaterally symmetrical, or because mirrors somehow reverse left-right but not up-down, or something else? And what did Aristotle think about such issues, and Descartes, Yeats, Newton, William James and Alice in her Wonderland? These answers and more are presented in an informing and entertaining manner in Mirrors in Mind.

The book begins with questions—some meaningful, some curious: Might multiple personalities appear multiply in a mirror? Which animals recognize their reflection as themselves and thus have the concept of self? When congenitally blind people who have successful cataract removal become sighted, how do they perceive mirror images? And what have artists understood about mirrors? X-ray examination reveals that Rembrandt changed a self-portrait that was first drawn incorrectly in mirror image. It seems interesting that very few artists incorporated mirrors in their paintings. Among those who did, however, many used mirrors to achieve perspective for their drawings and to produce illusions. In literature, Shakespeare was intrigued by reflections, and Gregory shows many places in which conceptual mirror-images are used in the Bard's plays.

Next, Gregory provides us with a selected history of mirrors, reflections and magical practices that cuts across time and countries and is filled with what some might call trivia and what all will call interesting detail. Then there is a review of classical optics (no mathematics required here) where Gregory argues that mirror reversal is not a problem to be explained, but instead is a confused interpretation that disappears when considered correctly. The reader who needs convincing of this will have to work through Richard Feynman's explanation for what we call mirror reversal found in the fourth chapter. This chapter and the next are introduced with Gregory's report that the ancient Greeks, and particularly Euclid, who wrote about light and mirrors, "thought of vision as working by rays shooting out of the eyes to touch surrounding objects." Gregory considers it curious that these ancients did not ask why rays could not be shot out at night. I would additionally ask why the ancients did not ask how the information returned to them to be seen.

Some other interpretations in the book might also be questioned, such as Gregory's description of the nature of light in which he notes that "light does not show wave and quantum properties at the same time. However, [apparently as a metaphor] a person is not happy and sad at the same time!" This does not quite describe the quantum mechanics of light. It is not that light does not have both properties at the same time; it is that we can never measure both properties simultaneously. For the metaphor to fit, it could be that someone is happy and sad simultaneously, but we cannot measure this.

Next comes a history of making mirrors, including materials, telescopes, mirror gadgets, kaleidoscopes and the magic involved. It is followed by a discussion of handedness which even includes the right-hand rule in electronics, and of the ambiguity of mirror images to illusions and perceptual distortions—-all of which is fun to read and much of which will be new to many people.

One cannot fully discuss mirrors without including Charles Dodgson's Alice in Wonderland and Alice Through the Looking-glass, from which Gregory quotes. From his thoughts about Alice's turning around because of mirrors, he reflects backward to Plato's images in the cave and forward to his own view that mirrors are not mysterious when we consider they reflect us as if we were turned around. He goes on to connect those thoughts to the more general importance of learning to interpret what we experience, for which he argues that "we need very carefully designed science centers—Exploratories and Explanatories—to learn how to interpret everyday experience without being misled." Gregory has been in his own exploratory all of his life, and he is a marvelous spokesman for educating children via play. In the final chapter, he briefly relates his reflections to mental models, Science (with a capital S), Pascal's calculating machine, intelligence and consciousness.

There is a lot here, from history to art, culture, optics, literature, science and philosophy, and there is no way that a single reviewer can evaluate the correctness or completeness of each reference. But the language flows smoothly, and essentially every sentence says something that is both interesting and often worth contemplating.—Gregory Lockhead, Psychology: Experimental, Duke University

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.