Milestones in Deep Time

By Steven Christian Semken

A geologist explores the lives of rocks and the roles they have played in history.

A geologist explores the lives of rocks and the roles they have played in history.

TURNING TO STONE: Discovering the Subtle Wisdom of Rocks. Marcia Bjornerud. 320 pp. Flatiron Books, 2024. $28.99.

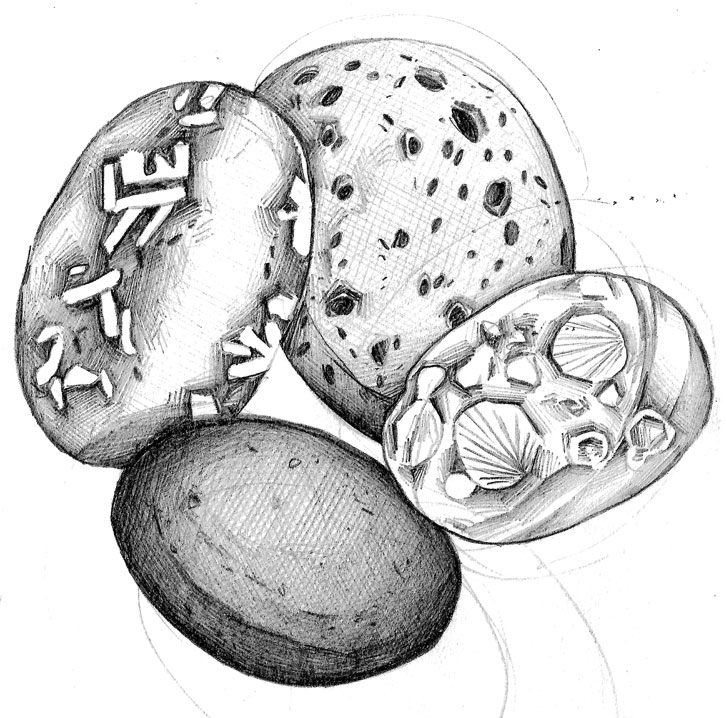

Turning to Stone: Discovering the Subtle Wisdom of Rocks, as its title indicates, is very much a book about rocks: their geoscientific interpretation and societal import, and the sometimes contentious history of how geologists have worked with them and learned from them. Marcia Bjornerud, a professor of geology at Lawrence University, has organized each of her chapters around a specific rock type such as sandstone, granite, dolomite, and eclogite. Each chapter transports the reader to a place where that rock can be found and is significant to the local geologic history. Each of these rock types, some common and some less so, has been “a protagonist at a certain time in [Bjornerud’s] life,” either when she was an inquisitive child or as an adult scientist. In the book’s front matter, she proffers a helpful schematic sketch of the geological environments where each of these types of rock originates, arrayed across the sea and the land, organizing and situating them for us in place, process, and time.

Haley Hagerman

Bjornerud is a structural geologist who specializes in unraveling the ways that tectonic forces in the solid, rocky shell of Earth, operating over millions to billions of years, leave records in physical and chemical attributes of rocks that scale from individual mineral crystals to entire mountain belts. Her explanations of the deep-time histories, ancient environments, and dynamic processes that can be read in the rock types that are assigned to each chapter are thorough and engaging. As a longtime teacher and public interpreter of geology, I admire Bjornerud’s flair for crafting clever and relatable metaphors that explain and summarize complex features and phenomena. Take, for example, her recognition of how an outcrop of diamictite, a rock with a haywire mix of large, angular gravel enclosed in fine mud, encoded the epic end of the Snowball Earth global icehouse event around 635 million years ago:

I realized that the rocks recorded a great acceleration, like a musical piece that starts very slowly and grows continuously faster. The mudstones below the diamictites, themselves thousands of feet thick, probably represented the depths of the Cryogenian ice age—a silent frozen world where almost no sediment was coming into the water and deposition occurred at a larghissimo pace. The varved layers represent an awakening, evidence that there were seasons again, and enough thawing for sand-size sediment to be delivered in yearly allotments to the seafloor, but the tempo is still adagio. Dropstones mean that icebergs are breaking off into open water, and they begin to accumulate in greater numbers—andante, allegro, vivace.

Bjornerud’s explanations of the geologic origin and significance of each rock type are well-crafted and evidence-based, and as a scholar of the history and epistemology of geology, she adds context by reminding us that our present understanding of these rocks was often born of dispute.

It is hard to grasp today that the origin of granite—the crystalline igneous rock that makes up the bulk of the continental crust by composition—was attributed by some esteemed 18th-century geologists to be deposition from sea water, rather than the solidification of magma. Bjornerud leads us through that episode and into an early 20th-century “delirium” that for a time possessed some otherwise sensible geoscience researchers: the idea that granite could have somehow formed by aqueous alteration of sedimentary rocks buried in the crust. She ends this narrative in the present, describing a developing hypothesis that the first appearances of granite may be associated with meteorite impacts on primordial Earth.

To Bjornerud, rocks are much more than geologic records to be deconstructed and argued over. They are also mentors, benefactors, and old friends. They humble her, but also offer reassurance in troubling times. They are not only evidence of Earth’s dynamism, but also its creativity. Bjornerud openly acknowledges having more than just an intellectual connection to rocks, and posits that she is far from alone in this: “I suspect, however, that most geologists are secretly in love with rocks.” Guilty as charged.

In addition to rocks, place is also a central theme in Turning to Stone. Field research is indispensable to the work of a structural geologist, and Bjornerud vividly describes campaigns from Norway to New Zealand, typically in remote, logistically difficult, and physically challenging settings. Isolation, weather, wildlife, and sometimes even earthquakes must be managed. But regardless of what obstacles present themselves, Bjornerud revels in these places and in her fieldwork. She makes herself at home in harsh conditions that many of us would just as soon steer clear of. We share in her satisfaction when she imparts that same enthusiasm for discovery to her students on field trips, shepherding their attention away from their phones to the rocks, and embracing all of their observations as if they were original findings.

More than simply a book about geology, it is also a memoir of a life rich with exploration, discovery, excitement, and collegiality—but not always an easy life. Bjornerud recounts a rural Wisconsin childhood in which progressive parents, the allure of natural environments, the accessible histories and artifacts of local settler communities, and the tragic legacies of depredations against Indigenous peoples, together mold her worldview. She embarks on her career in the heady days when plate tectonic theory was emerging to revolutionize nearly every aspect of the geosciences, but she must make her way and her name in a science that was (and still substantially is) dominated by men. Bjornerud attains a successful, though never fully comfortable, career as a tenured professor at a research university in Ohio, but eventually yields to her attachments to the Wisconsin landscapes of her youth. She moves her family back to where her children can enjoy their grandparents, and where she and her students can more easily put a hand lens to the rocks and structures that truly matter to her. She reboots her career at venerable but diminutive Lawrence University. A little more than a year later, she becomes her department’s sole faculty survivor: struggling to save her program from elimination and to winnow its infrastructure for migration to a new space, all while mothering three young boys on her own and doing what she can for a terminally ill husband from whom she is separated. Much like the exposed basement rocks of the nearby Canadian Shield, Bjornerud may be “worn down, but manage[s] to endure.” And eventually, to thrive.

With Turning to Stone, Bjornerud has augmented her portfolio of popular books and magazine articles that exemplify and advocate for a geocentric worldview: conversant with deep time, comfortable with incessant change, and respectful of natural laws. As a highly accessible chronicler of geological ideas and personalities, she could be considered something of an heir to the esteemed John McPhee—but Bjornerud reports from the inside, something McPhee himself was not able to do. The engaging narratives in her new book reveal that Bjornerud’s interwoven and wholehearted passions for rocks, her work, her science, her family, and her home are all as enduring as stone.

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.